The saddest part of Ghassan Tueni‘s introduction to The Beirut Spring, the book on the Cedar Revolution (which occurred following the assassination of Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in February 2005), lies in history. There have been many springs in the annals of Lebanon but the political summers have been inordinately short. Tueni begins his article with a photograph showing the Ottomans hanging Lebanese journalists for criticizing the ruling regime, a practice that is still in vogue though the means of execution are more modern. Tueni informs us that 90 years later, journalists — including his own son — were still dying through the agency of car bombs. Even the statuary of Beirut bears witness to many a withered spring. “The original Martyr’s Square statue, meticulously and skillfully sculpted from local stone in the 1920s, showed two women, a Christian and her veiled Muslim partner in hope. They also displayed unity in sorrow as the pair mourned their dead sons.”

When I was invited to visit Lebanon as part of a group of foreign journalists between February 12-19, I did not — and still do not — have any substantive experience in the politics of the country worth mentioning. But an article in the Atlantic turned up a serviceable introduction to the subject, which was to dominate the trip: whether Lebanon could shake itself free of Syrian domination and Iranian influence exercised through Damascus’ secret agents and Hezbollah in a region polarized by the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Lebanon was a proxy battleground between the geopolitical West and its foes in general, and between Israel and a Syrian-Iranian alliance at the regional level. But the axes of global, regional, and local conflicts did not line up so neatly on the ground. The global, regional, and local political powers had points of conflict and agreement at different levels and these were reflected in Lebanese politics. The result was a set of strange political alliances whose members were determined, nevertheless, to keep together until they agreed to part. The Saudis for example, were in the curious position of tacitly opposing Hezbollah alongside Israel, though they would never admit to that fact, because of a mutual fear of Iran. Hezbollah on the other hand, which preached a Shi’ite version of Islam, acted as a willing proxy of Sunni majority Damascus, in accordance with its alliance with Teheran.

The result of these criss-crossing lines of interest and allegiance was alliance politics, roughly divided between the broadly pro-Western, pro-Democracy March 14 Movement and the March 8 Alliance. The top three players in March 14 were the Sunni Future Movement, the Druze Progressive Socialist Party, and the Maronite Christian Lebanese Forces. In the rival March 8 alliance were the Shi’a Amal Movement, the Maronite Christian Free Patriotic Movement, and the Shi’ite Hezbollah.

What separated March 14 and March 8 political fronts was their competing visions of the future of Lebanon. March 14 wanted the Syrian/Iranians out while March 8 wanted the Syrian/Iranians in; at least for the present. That is the oversimplified but fundamental divide in Lebanese politics. Within these basic points of agreement, the coalition partners might compete or even fight on a plethora of minor issues. Indeed if the Israeli/Syrian Iranian problem were solved one way or another, the coalitions would probably reform along other lines. But first Lebanon had to get that far. And as the group of journalists met with the members of the March 14 coalition, the extraordinary variety of points of view — and the fundamental division along this basic fault line — became evident.

Like a play in two acts, the first glimpse of Lebanese coalition politics was at the rally to remember Rafik Hariri’s assassination on February 14. Hariri’s death marked Lebanon’s answer to the question of whether it would be allowed to escape Syrian domination. The answer was, “No, or you die”. At the rally, parts of which, are , the principal leaders of the Sunni, Druze, and Maronite parties spoke to hammer home the basic theme: Lebanon must be free to decide its destiny. In the service of that goal, all manner of hatchets were buried. It was a curious experience to hear the “Ave Maria” sung before the Hariri memorial mosque. And at the moment of silence to commemorate the actual assassination, the calls from the minarets mingled with the pealing of church bells through Martyr’s Square; a reminder of the time when some of these very coalition partners were at each other’s throats during the Civil War. The statue of the Christian woman and her veiled Muslim partner had been mourning for their sons a long time.

The Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) was a multifaceted war whose antecedents can be traced back to the conflicts and political compromises reached after the end of Lebanon’s administration by the Ottoman Empire. The conflict became greatly exacerbated by Lebanon’s changing demographic trends, the Palestinian refugee influx between 1948 and 1982, Christian and Muslim inter-religious strife, and the involvement of Syria and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). After a short break in the fighting in 1976 due to Arab League mediation and Syrian intervention, Palestinian-Lebanese strife continued, with fighting primarily focused in south Lebanon, occupied first by the PLO, then occupied by Israel.

During the course of the fighting, alliances shifted rapidly and unpredictably. By the end of the war, nearly every party had allied with — and subsequently betrayed — every other party at least once. The 1980s were especially bleak: much of Beirut lay in ruins as a result of the 1976 Karantina massacre carried out by Lebanese Christian militias, the Syrian Army shelling of Christian neighborhoods in 1978 and 1981, and the Israeli invasion that evicted the PLO from the country.

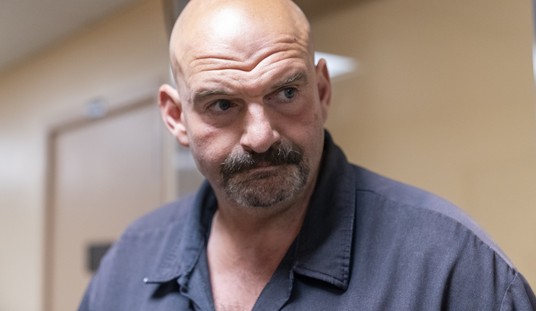

The following day, the second act began and the fascinating political combinations were on full display during our visit to Walid Jumblatt. Imagine a stone castle upon a high hill inhabited by a tribal leader who happens to be leftist in his political views, a one-time ally of Syria now dedicated to its eviction from the central role in Lebanese politics and you will have Jumblatt. And if it seemed impossible to top Jumblatt for improbability, that was disproved by the next night’s visit to the Maronite leader Samir Geagea. Where Jumblatt’s security arrangements seemed traditional, tribal, and even kingly, Geagea’s redoubt was thoroughly modern, Western, and scientific. Yet the man sitting at the end of these scientific defenses was a philosopher and mystic; a seasoned warrior who had spent 11 years of solitary a confinement in ascetic meditation and reading learned works until his 6 square meter cell was piled with books from floor to ceiling; until he hardly had room to walk; until even the thought of leaving the world of ideas he had come to love paradoxically terrified him.

Lebanon seemed particularly adept at producing scenes out of a motion picture; it was place where a stone fortress might contain a relic of the Cold War and a mountain stronghold might conceal a mystic. Involuntarily, the words of James Elroy Flecker’s Journey to Samarkand came to mind:

Beyond the last blue mountain barred with snow,

Across that angry or that glimmering sea,

White on a throne or guarded in a cave

There lives a prophet who can understand

Why men were born.

And maybe we had stood before him.

The message of these charismatic men was re-emphasized by all the minor players of the coalition: from a soberly dressed group from the Muslim Brotherhood, who were denouncing Israel when they weren’t excoriating Hezbollah, to a loose association secular, intellectual Shi’a who would be at home in any Western intellectual salon. In each case, the message was that Lebanon should be allowed to rule itself according to its unique constitutional arrangements. The alternative was re-subjugation to Syria, or worse — as some Sunni darkly feared — to Teheran. If the Lebanese state disintegrated, either because Hezbollah smashed the system or the communities were pushed too far, then the fragile unity that kept the country together might dissolve and it might revert, like a werewolf under the full moon, to sectarian conflict and civil war. Commitment to democracy was, in a way, the alternative to national suicide. The idea of Lebanon rested on an allegiance to a process rather than any specific outcome; it was the commitment to that method, which seemed to hold the March 14 movement together. Lebanon might acceptably shape-shift, depending on the exigencies of the moment, but it had to do so under certain rules or all bets were off. Stability for Lebanon seemed less a matter of attaining a definite policy, than adhering to definite process. The trouble with Syria and Iran, and their proxy Hezbollah, was that they wanted to replace consensus with hegemony. That would break the process and as a byproduct, possibly smash the country.

On February 18, our group of journalists met with senior Lebanese political figures and the question on everyone’s mind, with Senator John Kerry’s presence still fresh in the region, was what the United States was going to do regarding the peace process it was pushing in the region. Time and again it was emphasized that Lebanon’s fate, as the proxy battlefield of outside powers, was bound up in the way regional political conflicts were resolved. The Lebanese were deeply interested to know what the powers had in store for it. It was felt that one of the chief indicators was whether the International Tribunal, due to be convened in early March, would charge the Assad regime in Syria with Hariri’s murder. The Lebanese were watching the Tribunal’s actions with great interest, not simply as a criminal proceeding, but as a bellwether for the future of the International Community. Would Washington force Israel into concessions in an effort to “peel Damascus away from Teheran?” or would the peace process fall flat on its face and by miscalculation ignite yet another war between Israel and Syria/Iran/Hezbollah, with the Lebanese caught in between? There were many questions and no definite answers.

An account of the trip would be incomplete without some record of my personal impressions. Facts can be acquired from secondary sources but emotional information can only be gathered first hand. Actual people have a way of blurring categories: the terms Sunni, Shi’a, Maronite acquire, on the ground, a human face, and all of a sudden one is less convinced of one’s calculations than confirmed in the certainty of one’s ignorance. The ironic outcome of more information is to reduce false certainty. But if the future was analytically unforeseeable, in human terms the future seemed clear: Lebanon would be free one day, according to its lights. It was too complex to live under something like Hezbollah: like Dylan Thomas’ anonymous youth, it would sing in its chains like the sea.

Richard Fernandez of the Belmont Club, in Pajamas Media Express, was invited to visit Lebanon by the New Opinion Group between February 12 and February 19, 2009.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member