WASHINGTON – A retired brigadier general who served as deputy director for intelligence at the U.S. Africa Command during the 2012 attack on the consulate in Benghazi, Libya, told a House panel Thursday that military officials quickly realized the encounter was a “hostile action” by terrorists – not a protest-turned-violent as initially portrayed by the Obama administration.

Former Air Force Gen. Robert Lovell, who spent 33 years in uniform, told the House Oversight & Government Reform Committee that command headquarters in Germany didn’t know how long the Sept. 11, 2012, assault on the U.S. Consulate that resulted in four deaths, including that of Ambassador Chris Stephens, would last.

“Nor did we completely understand what we had in front of us, be it a kidnapping, rescue, recovery, protracted hostile engagement or any or all of the above,” Lovell said. “But what we did know quite early on was that this was a hostile action. This was no demonstration gone terribly awry.”

Lovell’s claim counters statements issued in the immediate aftermath by the White House and approved by the Central Intelligence Agency that asserted the confrontation arose as a result of an anti-Muhammad video that appeared on YouTube and led to widespread protests across the Muslim world.

The facts gathered by Africa Command quickly “led to the conclusion of a terrorist attack,’’ Lovell said.

Lovell is the first veteran of the Africa Command to counter the administration’s initial explanation of the incidents in Benghazi, rationales that have been criticized and questioned by Republicans since the time of the incident. But Jay Carney, President Obama’s spokesman, insisted on Thursday that citing the ant-Muslim video as the cause of the attack “was the best information we had at the time.”

“The fact that there were protests around the region threatening our embassies at the very same time is something that is often forgotten, but obviously affected the whole environment about how we perceived what was happening at the time,” Carney said. “And again, the implication is that we were somehow holding back information, when, in fact, we were simply saying what we thought was right. And when elements of that turned out not to be true, we were the first people to say so. It was based on what we knew at the time.”

Lovell also questioned the nation’s response to news about the attack, insisting that the State Department under then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton failed to ask the military to launch an operation to reach the Americans in distress, an action he said should have been taken even if that endeavor proved futile. Instead, the Pentagon reined in forces, asserting that personnel couldn’t have reached the scene in time to prevent any fatalities.

“There are accounts of time, space and capability discussions of the question, ‘Could we have gotten there in time to make a difference?’” Lovell said. “Well, the discussion is not in the ‘could or could not’ in relation to time, space and capability. The point is we should have tried. As another saying goes — always move to the sound of the guns.”

Lovell said there was “desperation” in Africa Command headquarters as military personnel sought to “gain situational awareness and to be able to do something to save people’s lives.”

“Basically, there was a lot of looking to the State Department for what they wanted and the deference to the Libyan people and the sense of deference to the desires of the State Department in terms of what they would like to have,” he added.

Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-Utah) asked if it was possible to reach the scene in time.

“We may have been able to, but we’ll never know,” Lovell said.

But Lovell’s revelation drew immediate doubt from an unexpected quarter. Rep. Buck McKeon (R-Calif.), chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, another panel looking into the Benghazi tragedy, said Lovell was not in a position to determine what was transpiring at the time.

McKeon said Lovell “did not serve in a capacity that gave him reliable insight into operational options available to commanders during the attack, nor did he offer specific courses of action not taken.”

“The Armed Services Committee has interviewed more than a dozen witnesses in the operational chain of command that night, yielding thousands of pages of transcripts, e-mails, and other documents,” McKeon said. “We have no evidence that Department of State officials delayed the decision to deploy what few resources DoD had available to respond.”

Ultimately, McKeon said, Lovell “did not further the investigation or reveal anything new, he was another painful reminder of the agony our military felt that night, wanting to respond but unable to do so.”

While Lovell’s comments drew most of the attention at the hearing, one witness, Dr. Kori Schake, a fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution, told the panel that the situation in Libya is tenuous.

“Libya is a failing state,” she said. “Security is deteriorating. Governance is ebbing. The security situation is limiting the economy in ways that prevent the state from utilizing its one major advantage — oil revenue. Without more encouragement and direct support, Libya’s tribes and regions will not come together by political means, they will fracture.”

The challenges facing Libya “have all been aggravated by Obama administration policy choices,” Schake said. “We overthrew the government without a plan for establishing security or helping stabilize fragile processes of democratization. We have ignored the growing aggressiveness of militia and activity of jihadists. We have been silent on an election marred by violence. We are not helping organize the parliamentary elections coming in a few months, which are likely to be a bellwether for legitimacy of democratic processes in Libya.”

Administration policies, she said, have primarily been concerned with “limiting our involvement rather than limiting threats emanating from Libya and assisting a society in transition from repression.”

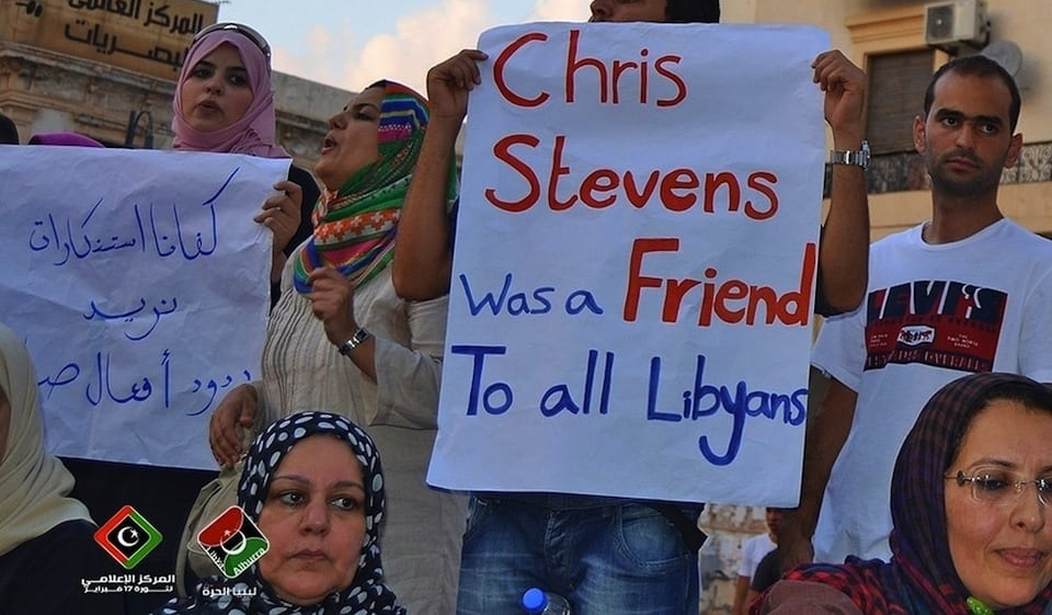

But Frederic Wehrey, senior associate in the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, asserted that it is up to the Libyans to address most of the problems themselves. In fact, he said, “overwhelmingly, Libyans remain supportive of the NATO-led operation. And they retain a degree of goodwill toward the United States that contrasts sharply with surrounding countries.”

The ultimate solution for Libya’s security woes, Wehrey said, lies in the political realm — the drafting of a constitution, reform of the General National Congress and broad-based national reconciliation.

“This is an area where the U.S. and other outside actors can lend advice and measured assistance, but where the ultimate burden must be borne by Libyans themselves,” he said.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member