John Steinbeck and Peru: two things I never thought might go together.

My wife, whom I appreciate very much, has a habit of purchasing for me unexpected and unrequested used books at random from here or there and surprising me with them.

This time, it was Steinbeck’s novel on the vast cultural and geographical landscape of the U.S.A, “Travels with Charley: In Search of America,” Charley being the French poodle he took with him gallivanting across the continent.

It was an odd juxtaposition, I’ll tell you, reading an accounting of my home country from 1961 while traveling in such a foreign locale as the “high jungle” of Peru.

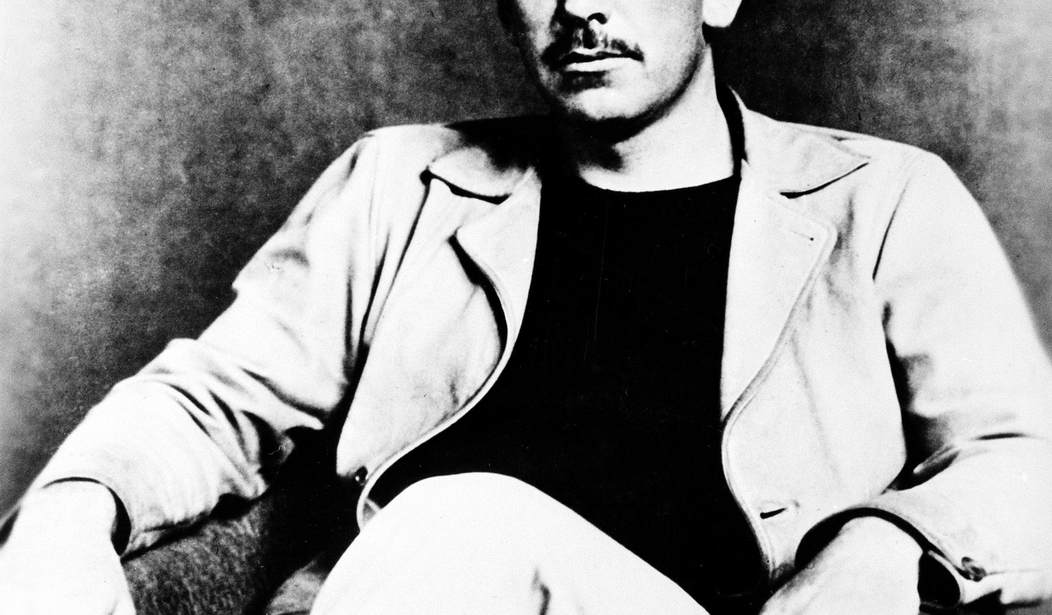

Steinbeck was pushing sixty when, out of restlessness and speculatively because he knew he was dying, he decided to transit the nation in an outfitted proto-RV called Rocinante (named after Don Quixote’s horse) and document what he found in written word.

I found many of the quotes apropos and relatable, particularly related to his self-admitted wanderlust, a recurring theme throughout the book:

I saw in their eyes something I was to see over and over in every part of the nation—a burning desire to go, to move, to get under way, anyplace, away from any HERE. They spoke quietly of how they wanted to go someday, to move about, free and unanchored, not toward something but away from something. I saw this look and heard this yearning everywhere in every states I visited. Nearly every American hungers to move...

When I was very young and the urge to be someplace else was on me, I was assured by mature people that maturity would cure this itch. When years described me as mature, the remedy prescribed was middle age. In middle age I was assured greater age would calm my fever and now that I am fifty-eight perhaps senility will do the job. Nothing has worked. Four hoarse blasts of a ships's whistle still raise the hair on my neck and set my feet to tapping. The sound of a jet, an engine warming up, even the clopping of shod hooves on pavement brings on the ancient shudder, the dry mouth and vacant eye, the hot palms and the churn of stomach high up under the rib cage. In other words, once a bum always a bum. I fear this disease incurable. I set this matter down not to instruct others but to inform myself....A journey is a person in itself; no two are alike. And all plans, safeguards, policing, and coercion are fruitless. We find after years of struggle that we not take a trip; a trip takes us.

I too, have had the burning desire to go anywhere but HERE all my life, particularly in my teens and twenties. Is that urge uniquely American? Maybe.

At many points throughout the novel, Steinbeck sounds much like a forerunner to the Unabomber three decades prior, whose manifesto regarding the impact of technological “progress” on society was, itself, prescient, speculating that what we call “progress” might have social and psychological consequences we can scarcely appreciate because we are biased to believe by default that the current state of affairs will continue indefinitely:

I wonder why progress looks so much like destruction…

We, or at least I, can have no conception of human life and human thought in a hundred years or fifty years. Perhaps my greatest wisdom is the knowledge that I do not know…

It occurs to me that just as the Carthaginians hired mercenaries to do their fighting for them, we Americans being in mercenaries to do our hard and humble work. I hope we may not be overwhelmed one day by peoples not too proud or too lazy or too soft to bend to the earth and pick up the things we eat.

Related: The Unabomber NAILED Liberal Psychosis in 1995

The reflections of such a poignant observer in his twilight are a worthy read — in Peru or his hometown of Salinas, California.