The last soldier of the Soviet army to leave Afghanistan was Colonel-General Boris Gromov, who marched at the back of a column of armored vehicles across the Hairatan “Friendship Bridge” connecting Afghanistan to the Soviet Union.

Presumably, Gromov was not happy with the outcome of that decade-long war. Crossing back into the Uzbek SSR, he cursed at reporters trying to interview him. He later explained that his words had been directed at “the leadership of the country, at those who start wars while others have to clean up the mess.”

Nevertheless, the last occupying forces from the Soviet 40th Army left in good order and Gromov walked the bridge with his chin held high.

For a fading empire, it was a moment full of both pride and shame.

Shame that they had lost a hard fought, nine-year-long war to primitive Mujahadeen. Pride that they had marched out the way they had.

Lester Grau, research coordinator for the Foreign Military Studies Office at Fort Leavenworth, wrote in 2007 that when Gromov led out those last troops, it was done “in a coordinated, deliberate, professional manner.”

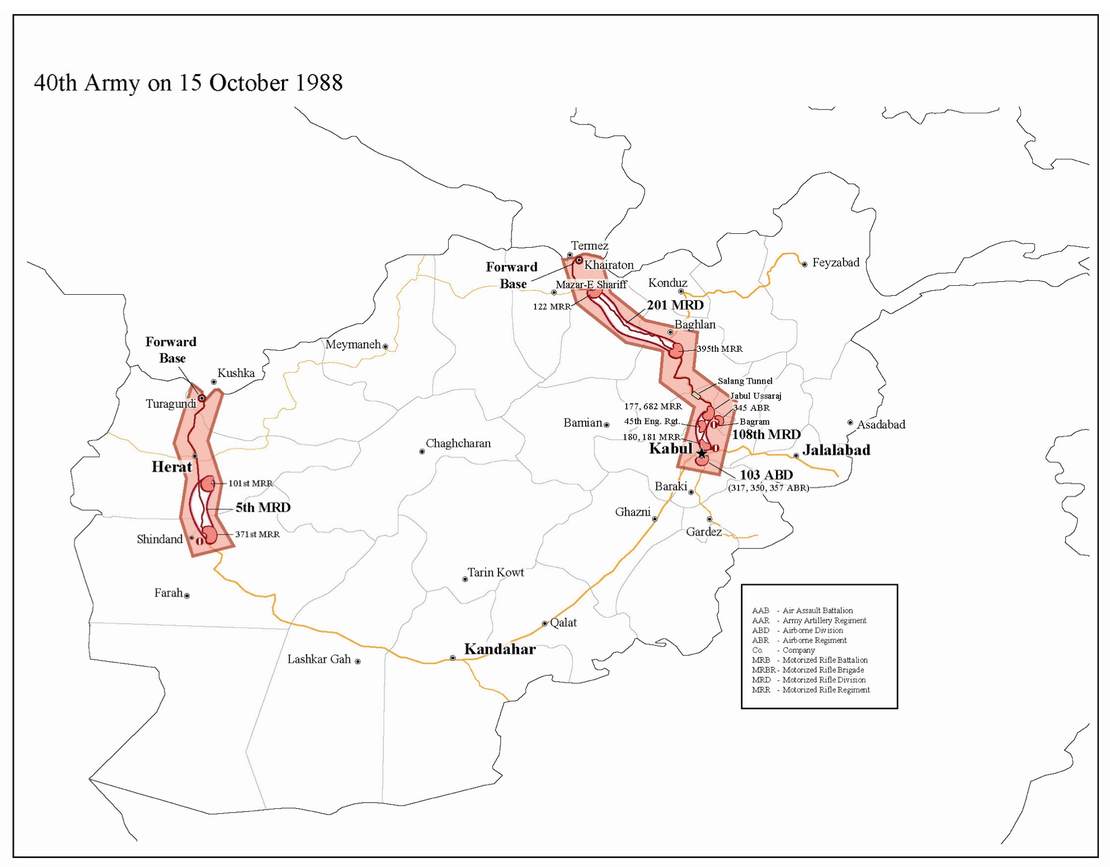

As you can see from this map showing the near-final disposition of the occupying 40th Army, the two major roads back to the USSR remained well-protected as the Red Army prepared to move its people — plus Soviet civilians and allied Afghans — north to safety.

The westernmost Soviet Forward Base at Turagundi was closed first, after the 5th Motor-Rifle Division had made a safe return home from Shindand, Herat, and other points along the strategic AH77 highway.

Only then did Gromov begin withdrawing his last three divisions north along AH62 toward the eastern Forward Base at Hairatan.

Both roads remained well-protected during the retreat, and the pro-Soviet government in Kabul managed to remain in power for another three years.

“The Soviet effort to withdraw in good order,” Grau wrote, “was well executed and can serve as a model for other disengagements from similar nations.”

Recommended: Who’s Really Driving the Afghanistan Disaster? Here’s a Clue.

Or disengaging from the exact same nation, 32 years later.

I’m no apologist for the Soviet Union.

The USSR was exactly what President Ronald Reagan called it in 1983: An “evil empire” and “the focus of evil in the modern world.”

Lenin’s Soviet Union was built on blood and an anti-human ideology, cemented into place by Stalin’s terror, labor camps, and totalitarian control over every aspect of human life.

It belonged on the “ash heap of history,” and that’s exactly where the USSR ended up, less than three years after Gromov crossed the Friendship Bridge.

The war was a brutal one, fought for bad reasons.

On Soviet strongman Leonid Brezhnev’s order, the Soviet 40th Army invaded Afghanistan on Christmas Day, 1979.

Their mission: To prop up the ruling Afghan communist government, whose brutal rule had driven much of the country into open revolt.

Before the Soviet invasion, there was no Taliban, there were no al Qaeda training camps. There was just an underdeveloped nation unlucky enough to be next door to an evil empire.

So please don’t think that by accurately describing Gen. Gromov’s orderly evacuation that I’m in any way excusing or promoting the policies or government of the USSR.

Gromov did, however, detail a proper retreat operation and then executed it well.

Flash forward to 2001.

With the best of intentions, our six-week war to topple the Taliban and the al Qaeda terrorists under their protection turned into a two-decade failed experiment at nation-building.

It was a less brutal war, initiated for the noble cause of ending a terrorist threat to American civilians. It ended as an expensive fool’s errand.

Like the Soviets, though, we had our fill.

Also just like the Soviets, the US military and our NATO allies had two routes out of Afghanistan. They were air routes, which does complicate things, but maybe not as much as you would think.

The United States Air Force excels at its airlift mission, and owns plenty of assets to effect an orderly withdrawal from almost anywhere on Earth to almost anywhere else on Earth.

A proper withdrawal plan would have gotten our people out of Kabul first. The airport there is small, and not being a major U.S. Air Force base (like the one in Bagram) has less capacity. As we saw to our horror over the last two weeks, it’s more difficult to defend, too.

Recommended: Donald Trump Warned Us What a Rushed Pullout of Afghanistan Would Like Back in 2017

Meanwhile, forces at Bagram could have continued supporting the Afghan Air Force, whose closure — basically ordered by Joe Biden! — ensured its rapid collapse due to lack of Western contractors who had provided much of its maintenance.

Once Kabul had been cleared of friendlies, we could then have gotten the majority of our people out via Bagram, with its perimeter defenders being the last to go.

This is textbook stuff. The Soviets showed how to do it by road, and we had the opportunity to do it by air.

But as my friend and colleague Bryan Preston noted earlier this week, the Pentagon was, for whatever reason, determined to do things exactly backwards.

So this is the question concerned Americans must ask ourselves, and we must be blunt with the answer.

How was it that a desperately mismanaged empire, quickly going bankrupt on its way to its final dissolution, managed to do what the richest and freest people in the world abjectly failed to do — and what does that say about our future as a great power?