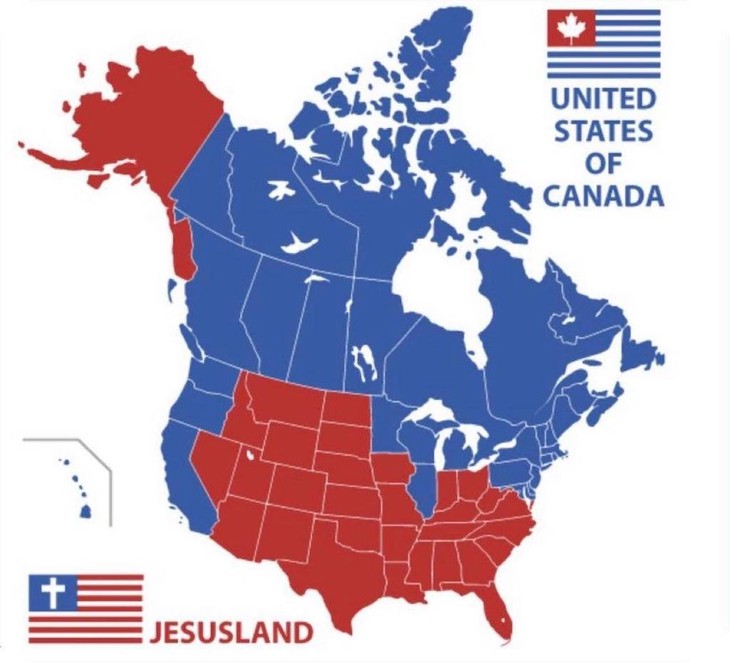

In a since-deleted tweet, lefty writer Amy Siskind “cheekily” suggested that the American Blue States join forces with Canada, while the rest of us Red State “welfare cases” get shoved off into “Jesusland.”

Is Amy a closet Kurt Schlichter fan?

It’s an old meme. Maybe you’ve seen it before.

In truth, there’s a long history of English-speaking peoples reordering themselves into new states, sometimes violently but mostly not.

English-speakers began the process of going global five centuries ago, and over time developed certain political instincts about how to maintain (or not maintain) “political bands which have connected them” to the mother country.

Compare and contrast the U.S. and Canada. We have here two sets of English-speaking colonies (leaving aside those troublesome Quebecois) occupying the same continent and sharing one of the world’s longest borders. One parted ways violently with Britain and embraced a revolutionary republican form of government. The other remains a loyal member of the Commonwealth and keeps the Queen on their currency.

Despite our serious differences, that long border we share is unguarded: No fortresses, no walls, no nothing but a few Customs checkpoints.

They have their system and we have ours, and our common English political and linguistic heritage has been enough to keep the peace for over 200 years.

Having learned its lesson from losing the 13 United States, London used a lighter touch on its other colonies, most of which remain in the Commonwealth. But would it really matter if Australia left or if the English-speakers in South Africa’s Cape petitioned to be let back in?

No, not much, although the South Africa situation would make for some very interesting headlines.

Another example: New Zealand was briefly a part of Australia’s New South Wales before the political entity known as Australia was formed. Australia might have been created with the Kiwis attached. Or maybe New Zealand would have been formed with bits of eastern Australia included. Whatever the case, there’s little doubt that the English-speaking inhabitants would have continued running their affairs in the orderly, peaceful way that has long been our habit.

There’s a republican movement in Australia dedicated to removing the British sovereign as their Head of State. If someday they win, not much would change in Australia, nor in Britain.

The westward expansion of the United States tells a slightly different story, but one containing a vital lesson about our political organization.

Rather than go to war among themselves over competing land claims, the original states agreed to give up those western claims, and allow the largely unsettled territories to someday form their own, equal states.

The same spirit that caused Englishmen to set sail across the ocean encouraged Americans to pioneer a continent.

Over time, those original 13 states became 48, and almost everywhere the process was basically the same. Settlers would self-organize their own local governments, and once they had enough inhabitants would petition for statehood.

(Texas is a special and more complicated example, and one I’ll leave to our resident Texas historian, Bryan Preston.)

What happened in American territory after American territory in the 19th and early 20th centuries became so common that we never think to marvel at it, but we ought to.

Upon settling a new region, Americans didn’t seek to weaken their political bands with Washington, but to strengthen those political bands by joining the Union.

You might expect that having kicked the Brits out, Americans wandering far from Washington might at least try to set up their own, independent nations somewhere out west.

But no.

There is probably more than one reason for that near-miracle, but the most important reason can be summed up in just one word: Federalism.

Missourans are not Utahans are not Californias, but it has been our good fortune that (at least until recent decades) we could all get along reasonably well.

“So what about the Civil War?” you might ask. Federalism provides enough political elbow room for people with differing ideas about government to all fit under the same constitutional republic. But there was no room for slavery to fit in with our broadening understanding of this country’s founding principle that all men are created equal in the eyes of the law.

The great irony of the Civil War is this: Today, the once-conquered Southern states remember and abide by this country’s founding principle far better than the Northern or West Coast states do.

If you want a good conversation with someone who appreciates the constitutional limits imposed on Washington by our federal structure, talk to someone in rural or suburban Texas or Alabama or Florida. If you want a lecture about how all 50 states must be homogenized under Washington’s stamping boot, talk to a Los Angeleno or a Chicagoan or a New Yorker.

By and large, rural and suburban Americans want to be left alone. By and large, urban Americans want to boss the rest of us around. The real Red/Blue divide doesn’t follow the nice, clean lines of Amy Siskind’s silly map. Instead, there are densely-populated Blue dots along each coast and scattered across the American interior, who have long since given up any notion of federalism.

Looking at the sad result of this last election, time might be running out to peacefully bridge that divide.

Looking again at that “United States of Canada” and “Jesusland” map, you have to wonder how much of Canada would remain blue, or whether Albertans, Saskatchewanians, and Manitobans would join with us federalism-lovers here in red America. I bet we could haul in the Yukon Territory, too.

Would Ottawa miss them? Or would Justin Trudeau say, “Yo, good riddance, eh” to the more conservative parts of Canada? All the while welcoming in Communist-held Portland and poop-strewn San Francisco.

Maybe it’s time for yet another re-ordering among the English-speaking peoples of North America — before things come to blows.

But I resent the map legend calling us “Jesusland.” Not because of the intended insult, mind you, but because “The United States” would still fit us just fine.

Those Red States represent whatever is left of the United States — and remain, as ever, the last, best hope of mankind.