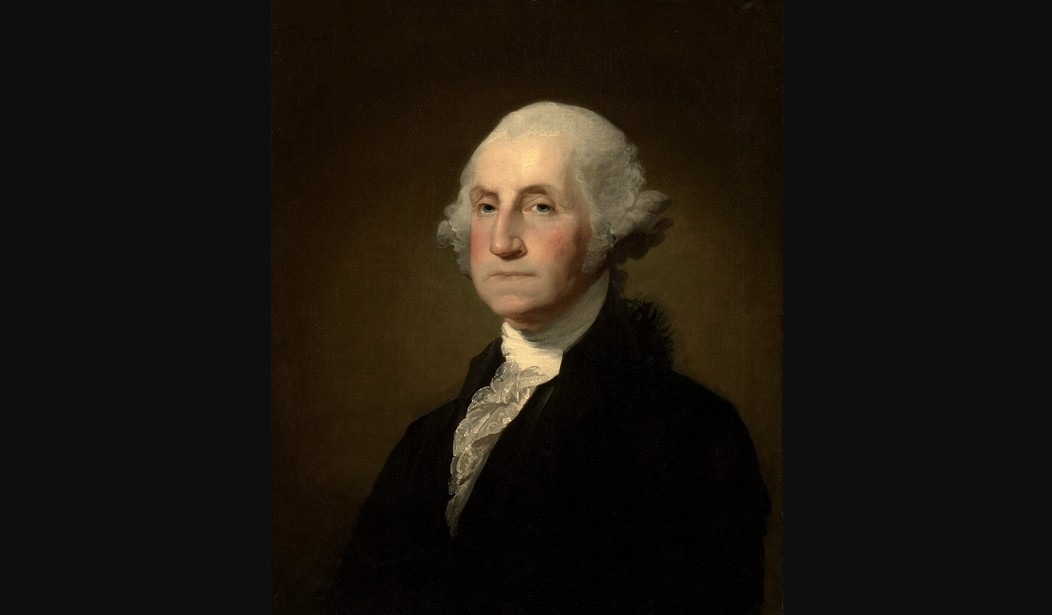

While President Abraham Lincoln gets credit for creating Thanksgiving as an annual national holiday, it was President George Washington who created the American tradition, when he designated Nov. 26, 1789, as a day to give thanks to God as a nation for our freedoms, our country, and all that He has given. This is excerpted from his 1789 Thanksgiving Proclamation:

By the President of the United States of America, a Proclamation.

Whereas it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor-- and whereas both Houses of Congress have by their joint Committee requested me to recommend to the People of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer to be observed by acknowledging with grateful hearts the many signal favors of Almighty God especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a form of government for their safety and happiness.

Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be-- That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks--for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation--for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his Providence which we experienced in the course and conclusion of the late war--for the great degree of tranquility, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed--for the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted--for the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed; and the means we have of acquiring and diffusing useful knowledge; and in general for all the great and various favors which he hath been pleased to confer upon us.

Washington made it clear that the nation owed much to the Creator for all of the progress it had made to that point. He also made it clear that it was his belief and that of his fellow leaders that the country’s fate rested in the hands of the Lord.

Before Washington’s proclamation, the story of the Mayflower and the Pilgrims was well understood and commonly recognized in various ways. But it was not a national thing. Local towns and villages marked the memory of those Pilgrims and their story in their own ways, and they added to the practice with local flavor and local meaning. Celebrations would follow successful harvests, military victories, or community deliverance from disease outbreaks.

The practice of celebrating Thanksgiving was patterned after “harvest home” festivals in Europe, and it was strongest in the New England region.

While gratitude was always at the core of the patchwork of observances throughout the colonies, Thanksgiving was not a national unifier.

Washington changed that.

During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress had declared days of thanksgiving to recognize certain military victories and the alliance with France. These were sporadic and very much connected to wartime events.

Washington became president in April 1789. The U.S. Constitution had just replaced the Articles of Confederation. Some states almost did not ratify the document. The new nation was starting to divide itself along political lines. Sound familiar?

Washington wanted to create a national identity, and he knew part of doing that was to create shared and unified civic traditions based on a common moral foundation.

The president knew that it was through basic national ritual that he could better bring the country together. He’d learned this as commander of the Continental Army, where he instituted a number of military traditions and rituals that unified both the troops and the people of the colonies, who together wanted to live in a free nation.

When Washington made his proclamation in October 1789, he made sure that it included gratitude for the Revolution’s military victory; the new nation’s unity under the Constitution; for peace, prosperity, and freedom; and for now having more responsibilities, as comes with self-governance.

There were some, even then, who did not favor a public celebration of thanksgiving for fear it would lead to the establishment of a state religion. Washington saw it differently.

He never mentioned a specific Christian denomination of faith, but in his writings, he consistently referenced his belief that God is the “author” of all human activity, that countries only flourish if they exhibit certain moral virtue, and that gratitude is an actual civic obligation.

In effect, Washington knew that he had more than a country to govern, but he had to create a truly American culture based on everything that came before. He knew that this particular civil ritual could heal the country after war and bridge divides between the states.

In 2025, some in American society find religion to be divisive, or they are the ones who make it so, but in 1789, for Washington, a nod to God for all of the good that had taken place was a departure from the day-to-day grind of heated political debate.

By that first Thanksgiving day in the newly formed United States of America, New Englanders and local leaders had embraced the ritual. Churches got involved. In the South, Thanksgiving observances were not as strong, with leaders from those states concerned about a federal government that might push religious observances.

Everything Washington did at this time scratched the surface of tensions between federal authority and states' rights, which we now know continued up until the American Civil War.

Still, that first Thanksgiving Day accomplished what Washington wanted it to accomplish.

In 1795, Washington issued a second Thanksgiving proclamation to reinforce the notion that a day to give thanks need not be a one-time thing, and that it should be more of a tradition in America.

Also for our VIPs: 'America 250' Tuesday: Spreading Word of the Revolution to All 13 Colonies

While Thanksgiving has religious undertones and core principles, it is decidedly not a religious holiday, and it is a uniquely American holiday. It was an important day in the creation of a new American identity.

When you sit down with your family this week, know that you are carrying out something that George Washington himself had envisioned, an American tradition that has survived to this day.