While reading a story about a new COVID-19 variant called R-1, blamed for 53 cases in California, I came across a line that needs to be corrected. “The R.1 variant proves that mutations will continue to take place. The most effective way to stop these mutations from happening is to get vaccinated.” You will hear statements like this about vaccines and mutations from the president on down. Everyone needs to be able to combat this idea.

First, viruses mutate when they face evolutionary pressure. Obstacles to the virus entering the cells of a host’s body to make copies of itself, also called replication, create this pressure. The immune systems of many unvaccinated people will provide no obstacles at all. Over the first four to five days of a COVID-19 infection, the person’s viral load will increase, then they become symptomatic and can transmit the virus to other potential hosts. There is almost no pressure on the virus to update its bag of tricks, or mutate, in this case.

Some people have been exposed to coronaviruses that are similar to SARS-CoV-2. They mount a faster immune response than those who are entirely naive or otherwise immunocompromised due to age or other illnesses. Natural immunity can be so effective that those individuals may never build a viral load sufficient to transmit it, so mutations by the virus do not get passed on. Alternatively, innate immunity works so effectively that the virus doesn’t have time to evolve.

Research has shown that those who have recovered from SARS-CoV-1 and other beta coronaviruses may have this immune response. Likewise, research on natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2 at Emory shows that patients recovered from COVID-19 have reactive immunity to SARS-CoV-1 and other viruses. During the H1N1 pandemic, a similar phenomenon occurred. Some people had reactive immunity to that virus based on exposure to influenza viruses similar enough to the new strain.

This cross-reactive immunity works because natural immunity develops to multiple parts of the virus. It’s different for everyone. Innate immunity causes the virus to face variable obstacles between individuals, making it challenging to mutate to evade it effectively. SARS-CoV-1 is about 20% different from SARS-CoV-2, but innate immunity to one reacts to the other based on what they have in common. All of the mutations of SARS-CoV-2 are a fraction of that percentage different from the original Wuhan variant.

So when are viruses most likely to mutate? When they encounter a similar immune response in many potential hosts. This situation is created by vaccinating large numbers of people to train their immune systems to work the same way. If the vaccine used is “leaky,” the vaccinated can be infected and transmit the virus. The pressure to bypass the vaccine-induced immunity causes mutations that are transmitted to others. This can happen even when the vaccinated person remains without symptoms.

There are indications that the current COVID-19 vaccines fit this description because the vaccinated can be infected and become symptomatic. Some studies demonstrate that the vaccinated can build viral loads at least as large as the unvaccinated, even if their symptoms are not as severe. High viral loads with mild to moderate symptoms create the perfect evolutionary environment for mutation.

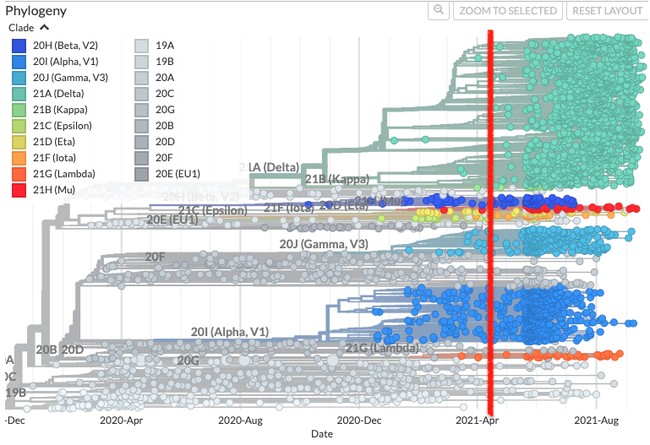

Nextstrain has been monitoring mutations globally. The red line in the graph below shows when the United States had vaccinated approximately 100 million Americans using the two mRNA vaccines primarily. It proceeds through the present, when almost 215 million Americans have received vaccines. Vaccination rates in much of Europe rose at rates similar to or faster than the U.S. during that period. Simply ask yourself, if each dot represents a mutation, when did the number for several of the common clades, like Delta, Gamma, and Alpha, explode?

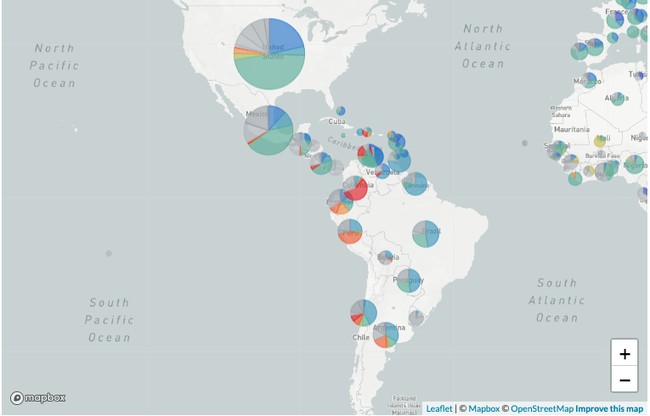

If you look at the red dots, the yellow dots, and the light and dark orange dots, they don’t change. The map explains this phenomenon. The Mu, Eta, Iota, and Lambda variants evolved in South America and Africa, where vaccination rates are mainly negligible.

Epsilon, Gamma, and Iota appear to burn out in the presence of the highly transmissible Delta variant. If you go to the Nextstrain site, you can hit play and watch the evolution of the virus over time. The pie charts on the map are the total share of each variant for the entire pandemic. When you watch the time lapse, you can see Delta has completely taken over the U.S. as the circle turns completely teal. However, you see Mu and Lambda hold their own, even with Delta in the mix. And these variants are headed to the U.S. over our open southern border.

Marek’s disease in chickens was the first time the phenomenon of a leaky vaccine, and its effect on viral mutation, demonstrated that the vaccinated can be dangerous to the unvaccinated. According to the author summary of the 2015 study:

There is a theoretical expectation that some types of vaccines could prompt the evolution of more virulent (“hotter”) pathogens. This idea follows from the notion that natural selection removes pathogen strains that are so “hot” that they kill their hosts and, therefore, themselves. Vaccines that let the hosts survive but do not prevent the spread of the pathogen relax this selection, allowing the evolution of hotter pathogens to occur. This type of vaccine is often called a leaky vaccine. When vaccines prevent transmission, as is the case for nearly all vaccines used in humans, this type of evolution towards increased virulence is blocked. But when vaccines leak, allowing at least some pathogen transmission, they could create the ecological conditions that would allow hot strains to emerge and persist. This theory proved highly controversial when it was first proposed over a decade ago, but here we report experiments with Marek’s disease virus in poultry that show that modern commercial leaky vaccines can have precisely this effect: they allow the onward transmission of strains otherwise too lethal to persist. Thus, the use of leaky vaccines can facilitate the evolution of pathogen strains that put unvaccinated hosts at greater risk of severe disease. The future challenge is to identify whether there are other types of vaccines used in animals and humans that might also generate these evolutionary risks.

Censored doctors and researchers started warning about the potential for this phenomenon when breakthrough cases in Israel began to rise. Some commenters raised it in the public comment period during the FDA hearing on booster shots. It may be part of the reason the experts did not recommend boosters for everyone. Right now, for all but the most vulnerable, the current vaccines seem to prevent severe illness and death. We also have monoclonal antibodies in our pocket to help those whose symptoms progress.

Some researchers you never see on CNN are convinced that the COVID-19 vaccines are “leaky” and are worried about the risks of a third dose. Others are insistent that the recovered, pre- or post-vaccine, should not receive a booster. But it is imperative to understand that we are not experiencing a pandemic of the unvaccinated. And the unvaccinated are almost certainly not producing the current array of variants.

Watch Dr. Ryan Cole explain the current state of the pandemic: