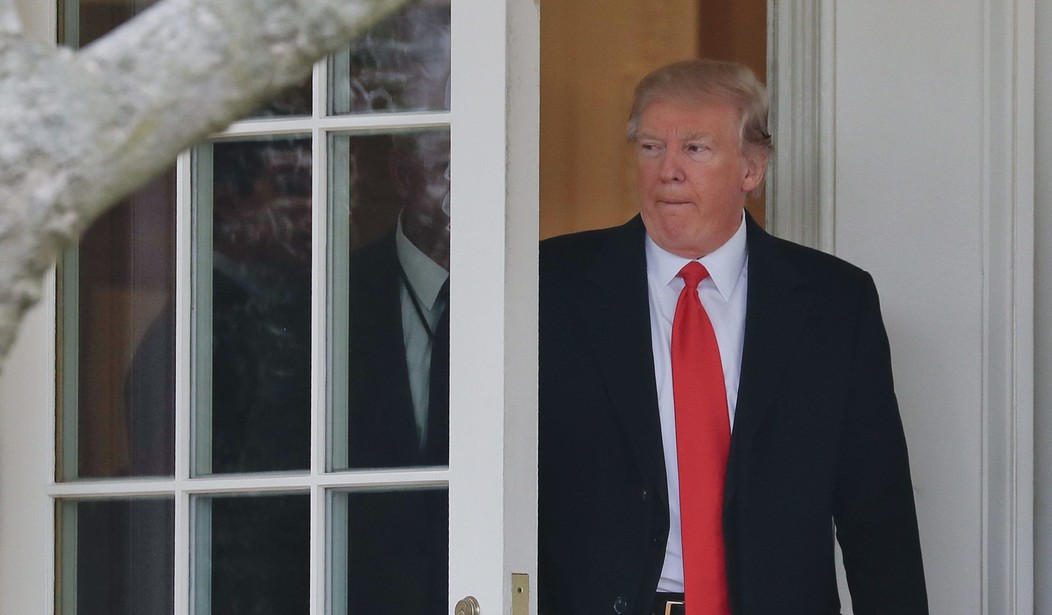

Donald Trump’s can-do optimism is his most prepossessing trait. As Georgetown’s Joshua Mitchell observed just before the election, positive thinking has been his life-long creed:

In New York City, Trump’s pastor was Norman Vincent Peale, whose 1952 blockbuster The Power of Positive Thinking was a palliative against the haunting presence of sin for the Anxious Christian, as well as against the dark psychological view of the human condition offered by Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents.

That is how Trump’s much-maligned musings about the Civil War should be understood. “Why couldn’t that one have been worked out?” he asked in a radio interview. “I mean had Andrew Jackson been a little later you wouldn’t have had the Civil War. He was a very tough person, but he had a big heart.” No sane person could fail to ask why 700,000 Americans (and nearly 30% of Southern military-age men) had to die in our bloodiest war. By the same token, no reasonable person could fail to ask why the Israeli-Arab conflict cannot be resolved.

America has no experience of tragedy, and Americans are poorly equipped to understand the tragedies of other peoples. Civilizations die, I argued in my 2011 book, because they want to. President Trump’s optimism is born of good will, but it is misguided. If he relies on the presumption that positive thinking and good will can solve all the problems of the world, he will waste his political capital wrangling with tragic problems.

In fact, the Civil War helps us understand why the Arab-Israeli conflict can’t be resolved, not any time soon, and not without considerable suffering, as I wrote in this 2003 Asia Times essay entitled, “More Killing, Please!” The Civil War was a tragedy, and not even Andrew Jackson (whose personal wealth derived from slave ownership) could have stopped it. No one should blame President Trump for his rescue fantasy: America has refused to acknowledge the depth of its own tragedy since we propagated the myth of the Gallant South and the Lost Cause, and a revoltingly apologetic pop culture version of the Civil War in works like “Gone With the Wind.” We aren’t inherently stupid. We have made ourselves stupid by averting our gaze from our own history.

More killing, please! (from Asia Times, June 12, 2003)

“I think people are sick of [killing],” said President George W Bush of the Israeli-Palestinian war. The contrary may be true. People may want the killing to continue for quite some time, as the Palestinian radical organizations suggest. A recurring theme in the history of war is that most of the killing typically occurs long after rational calculation would call for the surrender of the losing side.

Think of the Japanese after Okinawa, the Germans after the Battle of the Bulge, or the final phase of the Peloponnesian War, the Thirty Years War, or the Hundred Years War. Across epochs and cultures, blood has flown in proportion inverse to the hope of victory. Perhaps what the Middle East requires in order to achieve a peace settlement is not less killing, but more.

Mut der Verzweiflung, as the Germans call it, courage borne of desperation, arises not from the delusion that victory is possible, but rather from the conviction that death is preferable to surrender. Wars of this sort end long after one side has been defeated, namely when enough of the diehards have been killed.

Don’t blame the president’s provincialism. This has nothing to do with Bushido, Nazi fanaticism or other exotic ideologies. The most compelling case of Mut der Verzweiflung can be found in Bush’s own back yard, during the American Civil War of 1861-1865. The Southern cause was lost after Major General Ulysses S Grant took Vicksburg and General George G Meade repelled General Robert E Lee at Gettysburg in July 1863. With Union forces in control of the Mississippi River, the main artery of Southern commerce, and without the prospect of a breakout to the North, the Confederacy of slaveholding states faced inevitable strangulation by the vastly superior forces of the North.

Nonetheless, the South fought on for another 18 months. Between Gettysburg and Vicksburg, the two decisive battles of the war fought within the same week, 100,000 men had died, bringing the total number of deaths in major battles to more than a quarter of a million. Another 200,000 soldiers would die before Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox in April 1865. The chart below shows the cumulative number of Civil War casualties as the major battles of the war proceeded.

The chart is demarcated into sections labeled “Hope” (prior to Gettysburg and Vicksburg) and “No Hope”. Geometers will recognize a so-called S-curve in which the pace of killing accelerates immediately after Gettysburg and Vickburg and remains steep through the Battle of Cold Harbor, before leveling off in the last months of the war. Not only did half the casualties occur after the war was lost by the South, but the speed at which casualties occurred sharply accelerated. The killing slowed after the South had bled nearly to death, with many regiments unable to field more than a handful of men.

In all, one-quarter of military age Southern manhood died in the field, by far the greatest sacrifice ever offered up by a modern nation in war. General W T Sherman, the scourge of the South, explained why this would occur in advance. There existed 300,000 fanatics in the South who knew nothing but hunting, drinking, gambling and dueling, a class who benefited from slavery and would rather die than work for a living. To end the war, Sherman stated on numerous occasions these 300,000 had to be killed. Evidently Sherman was right. For all the wasteful slaughter of the last 18 months of the war, Southern commander Lee barely could persuade his men to surrender in April 1865. The Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, called for guerilla war to continue, and Lee’s staff wanted to keep fighting. Lee barely avoided a drawn-out irregular war.

What will happen now in the Middle East? At the outbreak of the war, Grant and Sherman were unknown. They rose to command because the nerve of their predecessors snapped at the edge of the abyss. The character of the war was too horrible for them to contemplate. Bush’s nerve appears to have snapped, as I predicted ( Bush’s nerve is going to snap, March 4), “The danger is that America will find itself fighting a sort of Chechnyan war on a global scale. President George W Bush cannot wrap his mind around this,” I wrote then. “The blame lies at the doorstep of the neo-conservative war-hawks who persuaded the president that America should undertake a democratizing mission among a people who never once voted for their own leaders.”

For that matter, Ariel Sharon’s claim before last week’s Likud party congress that Israel had achieved victory against terrorism was both accurate and misleading. Wars do not end when they are won, but when those who want to fight to the death find their wish has been granted. Sherman’s 300,000 fanatics could not face the mediocre circumstances of a South without slaves and were willing to die for their way of life.

Three million Palestinians packed into a narrow strip of land one day may accept the modest fate of a small and impecunious people, but their young people do not seem ready to do so. We do not know how many ever will. The killing will continue for some time before we find out.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member