Hurricane forecasters are bewitched, bothered, and bewildered. The Atlantic hurricane season was supposed to be epic. Instead, it's turned into a real dud.

Huge storms wreaking havoc on coastlines from Aruba to Long Island were supposed to line up in the Eastern Atlantic in June and hit us one at a time until late September. The damage was going to be historic and the TV coverage was going to give climate change fanatics plenty of air time to vent that "this is just a foretaste" of what's to come.

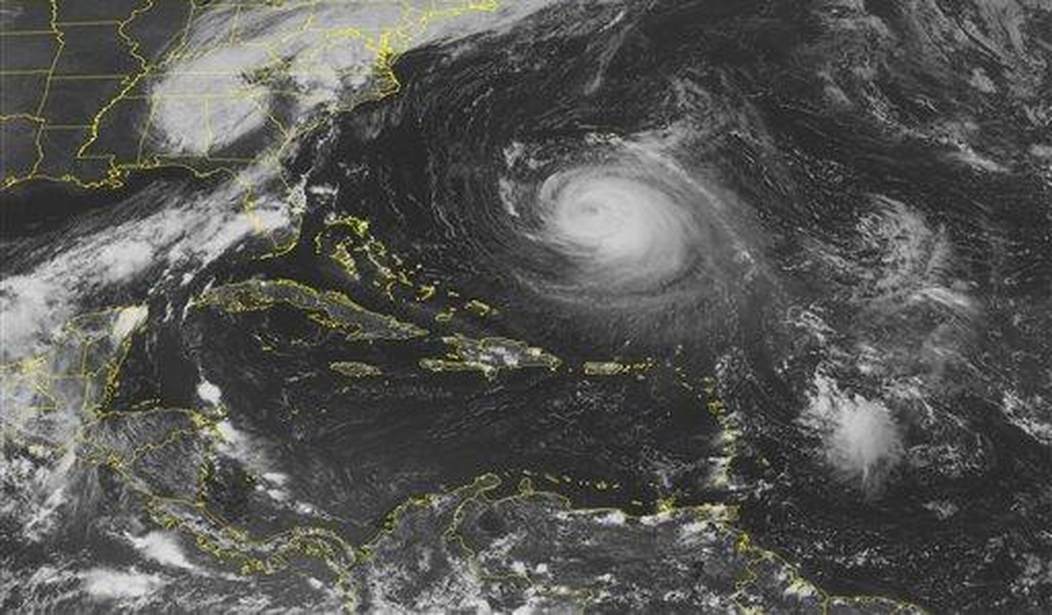

But something puzzling occurred on the way to hurricane Armageddon: not much has happened. The Atlantic Ocean has seen five named storms: two tropical storms, two hurricanes and one major hurricane this season.

“We definitely got started with an extremely active season,” says Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami.

Indeed, Beryl achieved Category 5 status earlier than any other hurricane in history. The July storm had meteorologists and forecasters scrambling for superlatives.

"I think it is kind of an omen of what the hurricane season will be,” says Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami. “I think we will see some pretty amazing outlier events happen.”

Alas, the internet is forever. And McNoldy's "omen" proved to be something much less. There hasn't been a named storm since August 21 and the conditions, still optimum for large, dangerous storms to form, aren't producing the killer hurricanes forecasters predicted.

The predictions and the reality of what's happening point to the dangers for scientists who rush to judgment about a hypothesis based on wishful thinking. Scientists don't know why hurricanes aren't forming at the rate expected. All the elements are present for big storms to form early and often. But they aren't. And while there's still a chance that we will be slammed by one or two major hurricanes, the hurricane forecasts prove that we still have much to learn about this planet and its weather.

Kelly Núñez Ocasio, an atmospheric scientist at Texas A&M University, believes the problem with the forecasts for the Atlantic hurricane season starts in Africa.

The West African monsoon is a seasonal wind pattern that carries rain from the Atlantic Ocean over into West Africa between June and September. Núñez Ocasio has studied how the monsoon affects the seeds of hurricanes. And in a paper published earlier this year, she and her colleagues modeled how the atmosphere responds to additional moisture.

Those simulations suggest that in wetter conditions, the West African monsoon pushes a band of air called the African easterly jet northward. Under normal conditions, that jet produces atmospheric disturbances called African easterly waves, which can become hurricanes once they reach the Atlantic. But when the jet is in a more northern position, it seems to inhibit the development and survival of these waves, Núñez Ocasio and her colleagues found, making hurricanes less likely despite all the moisture.

Even though the water is 50% warmer than normal for this time of year, giving tropical depressions plenty of energy to spin up really big storms, the factors that contribute to the formation of storms aren't present.

Nunez Ocasio also points to a huge dust cloud aloft in the Western Sahara. The cloud is very dry and keeps the wet air from contributing to creating a big storm

“I don’t see it changing so dramatically that we’re going to see, all of a sudden, a fast spin-up of multiple hurricanes before October,” Núñez Ocasio says. “It’s just too stable, and when conditions are stable, it’s hard to make it unstable. It’s going to take quite a bit.”

That hasn't stopped scientists from warning that things could always get worse.

“Conditions still appear very favorable for above normal activity during the remainder of the hurricane season,” says Jamie Rhome, deputy director of NOAA’s National Hurricane Center.

There's a lesson to be learned from the errors in hurricane forecasting. While we know a lot about the weather and how hurricanes form, what we don't know far exceeds our stored knowledge of how complex, chaotic systems behave to create deadly storms or a bright, sunny day.

It's a lesson that will go unlearned by many who could use that knowledge to realistically predict climate change.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member