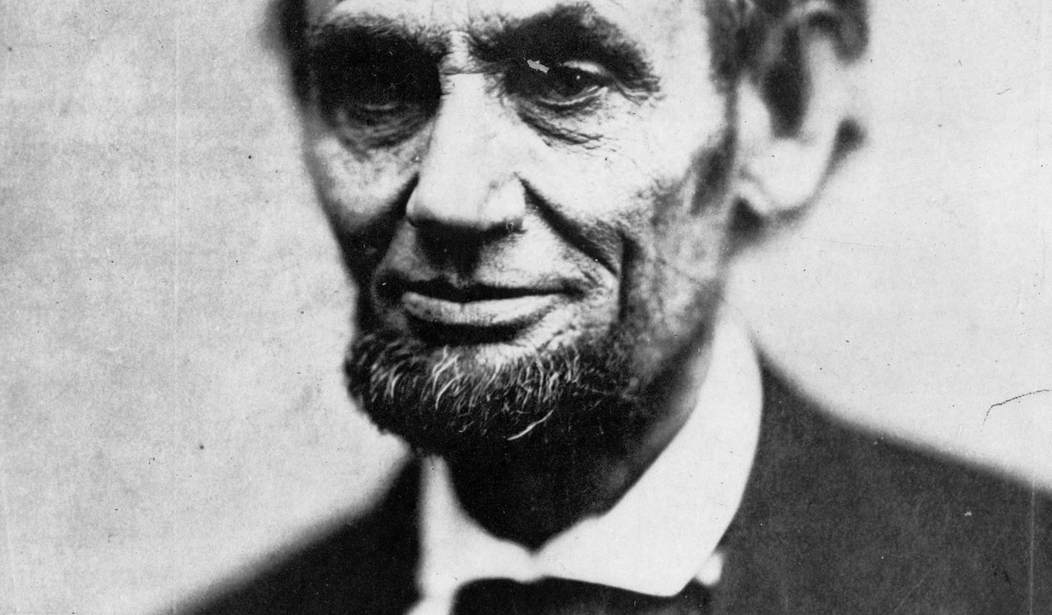

“The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here,” said Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg 156 years ago today. Would he really be surprised that the 247 words he scribbled two pieces of paper (not on the back of an envelope) to give a “few appropriate remarks” at the dedication of the cemetery at Gettysburg would go down in history as The Great Emancipator’s greatest utterances?

I think he would be. There was no artifice to Lincoln’s public speeches. After all, he was to follow the greatest orator of the age, Edward Everett, and was apparently only invited to the dedication ceremony as something of an afterthought. The invitation to Lincoln to attend and make his “appropriate remarks” wasn’t sent until November 2

In those days, listening to political orations was the national pastime. And Everett was a superstar. In an age before microphones, he enthralled audiences with his booming, expressive voice, flowery language, and exaggerated gesturing. He was a former congressman, Senator, governor of Massachusetts, secretary of state, and president of Harvard — easily one of the greatest Americans of his time. His speech at Gettysburg was full of classical allusions, poetry, and shameful emotional manipulation.

And the people ate it up.

But after he spoke and heard Lincoln speak, he wrote the president, “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

The “central idea of the occasion” was to consecrate the ground where 150,000 Americans came to death grips on the battlefield to decide the future of the United States. A weighty job it was. There were 3.200 Union soldiers buried there and given the gravity of the event, the commemoration deserved as much pomp and circumstance as possible.

But Lincoln rode up on his horse rather than arrive by ornate carriage. He was seated near the end of the dias — something of a lost personality among the star politicians and generals who attended. While Everett gave his oration, the president listened attentively. He was hatless and his wispy hair must have blown in the breeze that wafted across the cemetery.

That there was even a cemetery at Gettysburg was due to a local attorney, David Wills, who suggested the idea to the War Department. There was a little controversy when some Confederate soldiers ended up being buried there.

According to the National Park Service, Confederate soldiers were moved from the Gettysburg National Cemetery to cemeteries in Virginia, Georgia, North Carolina and Carolina, however, “a few Confederates do remain interred at Gettysburg National Cemetery.”

Interestingly, even before Lincoln spoke, one of the burial details asked a chaplain whether they should separate the bodies and bury them by state. The chaplain reportedly said, “No, no mix ’em all up. I am sick of states’ rights.” And that was the thrust of Lincoln’s message at Gettysburg. He couldn’t consecrate what had already been consecrated by blood. But the job of Americans was to honor that sacrifice by uniting the country and that “from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion.” That cause was unity and that no state, or group of states, could change that.

We’ve often heard it said that before Gettysburg, the U.S. was known as “these United States” and afterwards, as “the United States.” This is what Lincoln was striving for. And he used the honored dead at Gettysburg to drive home the point.

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate-we can not consecrate-we can not hallow-this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us-that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion-that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain-that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom-and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member