It was an overcast and warm day in June of 1987 when Ronald Reagan stepped to the podium at the Brandenburg Gate to deliver what many believe was his most memorable speech.

What made it memorable was the brutal honesty that Reagan used to describe the world as it was in 1987.

And now the Soviets themselves may, in a limited way, be coming to understand the importance of freedom. We hear much from Moscow about a new policy of reform and openness. Some political prisoners have been released. Certain foreign news broadcasts are no longer being jammed. Some economic enterprises have been permitted to operate with greater freedom from state control.

Are these the beginnings of profound changes in the Soviet state? Or are they token gestures, intended to raise false hopes in the West, or to strengthen the Soviet system without changing it? We welcome change and openness; for we believe that freedom and security go together, that the advance of human liberty can only strengthen the cause of world peace. There is one sign the Soviets can make that would be unmistakable, that would advance dramatically the cause of freedom and peace.

General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization: Come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

No president had ever spoken so frankly, so directly about the evil of the Soviet Union. And Reagan’s advisors nearly had apoplexy trying to keep him from calling for the destruction of the Berlin Wall. There was much hand-wringing at the White House and State Department over the phrase “Tear down this wall” as the speech’s author Peter Robinson relates:

With three weeks to go before it was delivered, the speech was circulated to the State Department and the National Security Council. Both attempted to squelch it. The assistant secretary of state for Eastern European affairs challenged the speech by telephone. A senior member of the National Security Council staff protested the speech in memoranda. The ranking American diplomat in Berlin objected to the speech by cable. The draft was naïve. It would raise false hopes. It was clumsy. It was needlessly provocative. State and the NSC submitted their own alternate drafts—my journal records that there were no fewer than seven—including one written by the diplomat in Berlin. In each, the call to tear down the wall was missing.

But Reagan wouldn’t let go of it:

A few days before the President was to leave for Europe, Tom Griscom received a call from the chief of staff, Howard Baker, asking Griscom to step down the hall to his office. “I walked in and it was Senator Baker [Baker had served in the Senate before becoming chief of staff] and the secretary of state—just the two of them.” Secretary of State George Shultz now objected to the speech. “He said, ‘I really think that line about tearing down the wall is going to be an affront to Mr. Gorbachev,'” Griscom recalls. “I told him the speech would put a marker out there. ‘Mr. Secretary,’ I said, ‘The President has commented on this particular line and he’s comfortable with it. And I can promise you that this line will reverberate.’ The secretary of state clearly was not happy, but he accepted it. I think that closed the subject.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

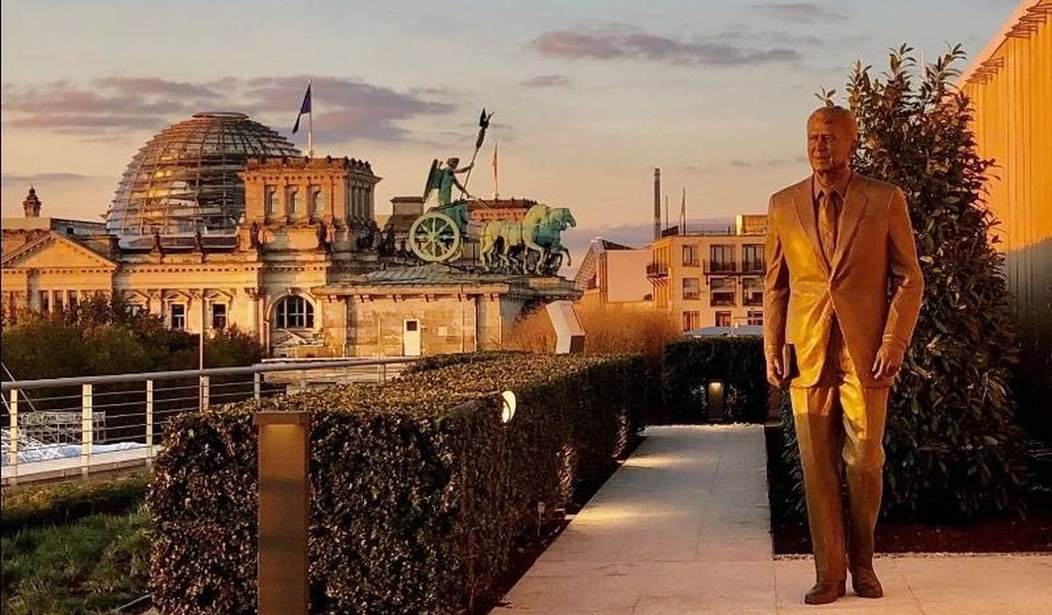

And some of that history was unveiled last night as part of the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall — November 9, 1989. A statue of President Reagan near the Brandenburg Gate at the U.S. embassy was unveiled:

Today we dedicated a statue of Ronald Reagan atop the US Embassy Berlin on the new Ronald Reagan Terrace. #BerlinWall30 pic.twitter.com/uZ2hGv6hST

— Richard Grenell (@RichardGrenell) November 8, 2019

The statue, a 7-foot-tall likeness of Reagan walking, was a long time coming. City officials had declined multiple requests by the United States to honor him with a statue. Berlin officials said a statue was unnecessary because Reagan was already an honorary citizen of the city.

This year, the statue came to fruition after U.S. Ambassador to Germany Richard Grenell proposed the U.S. erect a statue on its own accord at the embassy.

The dedication for the monument took place Saturday to commemorate 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Most historians try their best to deny Reagan had anything to do with the fall of the Berlin Wall. It was all Gorbachev’s doing, they claim. But that criticism fails to take into account the moral power of Reagan’s words, which Berliners remember to this day as the beginning of the end of communism. They don’t need any historians to tell them the impact that speech had behind the Iron Curtain.

The Soviet Union was a rotting carcass on the edge of a cliff and Reagan gave it a good, swift kick to finish it off. There may not be a direct correlation between Reagan’s words and the fall of the Wall, but to dismiss the speech as irrelevant is politics, not history.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member