As 2021 begins, some new trends are already emerging. Third-world political elites are privately acquiring COVID-19 vaccines and activists are advocating a social justice basis to allocate it internationally.

Argentina, South Africa, Brazil, and Turkey will have to be satisfied with Pfizer’s gratitude, because (like most countries in the world) they won’t be receiving enough of the vaccine to inoculate their populations, at least not anytime soon.

Meanwhile, the U.S. and Germany — along with Canada and the rest of European Union — have contracted for enough doses of various Covid-19 vaccines to inoculate their populations several times over. …

An international initiative to ensure equitable access to the vaccine, called the COVAX Advance Market Commitment and governed by the public-private health alliance Gavi, aims to provide participating countries with enough vaccines to inoculate up to 20 percent of their populations by the end of 2021.

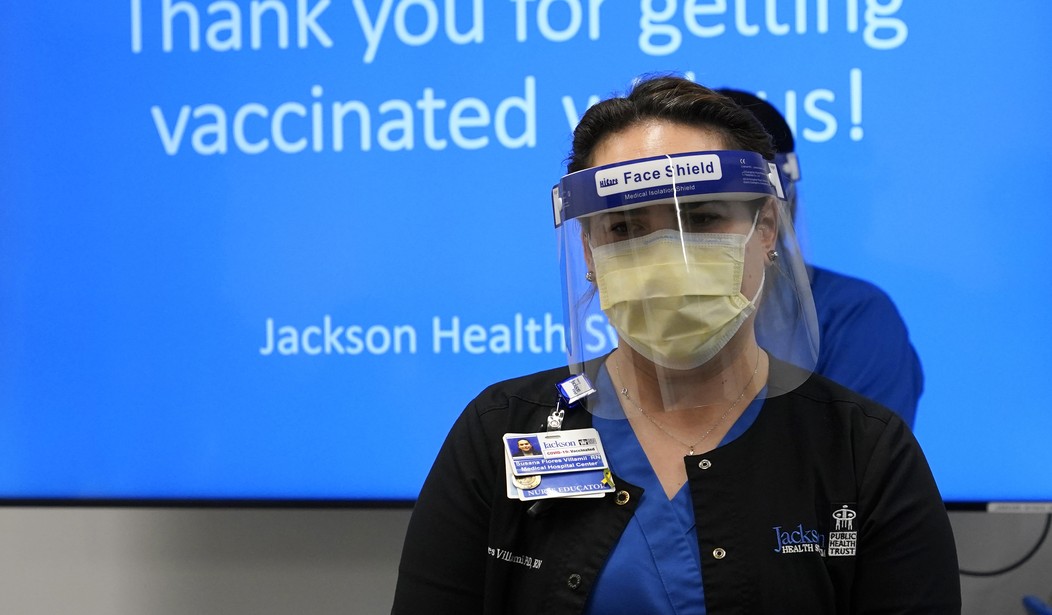

Even as some are cadging drugs, the Los Angeles Times reports that many American health care workers paradoxically want to refuse it. “So many frontline workers in Riverside County have refused the vaccine — an estimated 50% — that hospital and public officials met to strategize how best to distribute the unused doses.”

The vaccine doubts swirling among healthcare workers across the country come as a surprise to researchers, who assumed hospital staff would be among those most in tune with the scientific data backing the vaccines. …

The extent to which healthcare workers are refusing the vaccine is unclear, but … A recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 29% of healthcare workers were “vaccine hesitant,” a figure slightly higher than the percentage of the general population, 27%.

Politics has always been a big part of the covid crisis and it has moved from the lockdown to the vaccine phase. While the rapid development of effective pharmaceuticals pleasantly surprised skeptics, only a few countries/companies have the know-how to participate.

“I think the one thing COVID-19 has shown us, unfortunately, is that we weren’t prepared,” says James Bruno, president of the consulting firm Chemical and Pharmaceutical Solutions. “We have disrupted the entire supply line,” he says, through years of rampant outsourcing of the production of essential medicines to China and India and a steady decrease in the number of US firms in the business of making pharmaceutical chemicals.

Industry actually had to make war-emergency efforts to create production lines even before they were certain which vaccine formulations would work. A chemical engineering story from 2020 describes the frenzied preparation to make even limited supplies possible.

Contract manufacturers say they have been working for months putting capacity in place and are on track to hit targets for full-scale production going into 2021.

“Since we signed the agreement with Moderna in May [2020] … the focus has been on getting four manufacturing kits up and running, each capable of producing an estimated 100 million doses of mRNA 1273 per year.”

The company started operations at Portsmouth in July. Lonza has since scaled up the facility and is producing mRNA vaccine for the US market, Goerke says. The company is completing construction of three production lines in Visp to supply markets outside the US. Production is scheduled to begin by the end of the year.

Goerke says Lonza is able to move quickly in Switzerland because of a 2018 investment at the site that added prebuilt “shells” equipped with central services and utilities.

Producing lipids for Moderna’s vaccine is a job that requires a high level of expertise, according to Matthieu Giraud, director of peptides, lipids, and carbohydrates at CordenPharma. The German services firm is supplying the excipients from three facilities in Europe and one in Boulder, Colorado. CordenPharma will supply Moderna with standard lipids, including phospholipids, in addition to custom lipids.

“We anticipated the launch, and we have already done the ramp-up,” Giraud says. “We have almost reached now the maximum capacity that we are going to need, and, in theory, we cover almost three to four times the maximum capacity they ask us to cover.”

CordenPharma says it has had to engineer a greater than tenfold increase in lipid capacity this year. “It hasn’t been easy,” Giraud says. “We had to leverage our whole network.”

These herculean efforts went largely unnoticed by a media psychologically stumbling through the sands of 2020 toward a New Year and new administration, only to discover, as the Atlantic warns, that the world might face a second year of crisis.

The virus now has so much momentum that more infection and death are inevitable as the second full year of the pandemic begins. “There will be a whole lot of pain in the first quarter” of 2021, Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told me.”….

On the Fourth of July, Ashish Jha wants to host a barbecue at his house in Newton, Massachusetts. By then, the state expects to have rolled out COVID-19 vaccines to anyone who wants one. The process will be bumpy, but Jha is hopeful. He thinks that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus will still be spreading within the U.S., but at a simmer rather than this winter’s calamitous boil. He expects to keep all his guests outside, where the risk of transmission is substantially lower. If it starts raining, they could come indoors after putting on masks. “It won’t be normal, but it won’t be like Fourth of July 2020,” says Jha, the dean of the Brown University School of Public Health. “I think that’s when it’ll start to feel like we’re no longer in a pandemic.”

How soon that happens depends on politics and industry and nature itself. Another Atlantic article warns: “A new variant of the coronavirus is spreading across the globe. It was first identified in the United Kingdom … officials announced that America’s first case of the variant had been found in the United States, in a Colorado man with no history of travel, an additional case was found in California.”

A more transmissible variant of COVID-19 is a potential catastrophe in and of itself. If anything, given the stage in the pandemic we are at, a more transmissible variant is in some ways much more dangerous than a more severe variant. That’s because higher transmissibility subjects us to a more contagious virus spreading with exponential growth, whereas the risk from increased severity would have increased in a linear manner, affecting only those infected.

Though this mutation could prove deadly, nobody knows for sure. As the reluctance of American health care workers shows, there are as many dead predictions this year as hospital patients. The longer the pandemic lasts, the higher the cumulative fatality rate among expert reputations.

The coronavirus pandemic redistributed power and economic advantage on a vast scale. The advent of vaccines not only creates new political opportunities, it also renders the older ones, like those involving masking and lockdowns, obsolete. The narratives like ‘the virus must mutate.’

The biggest difference between today’s covid and the far more lethal Spanish Flu, the Atlantic notes, is cultural awareness. The magazine didn’t even notice the 1918 virus at the time. Nobody’s going to make that mistake again.

The influenza pandemic that began in 1918 killed as many as 100 million people over two years. It was one of the deadliest disasters in history, and the one all subsequent pandemics are now compared with.

At the time, The Atlantic did not cover it. In the immediate aftermath, “it really disappeared from the public consciousness,” says Scott Knowles, a disaster historian at Drexel University. “It was swamped by World War I and then the Great Depression. All of that got crushed into one era.” An immense crisis can be lost amid the rush of history, and Knowles wonders if the fracturing of democratic norms or the economic woes that COVID-19 set off might not subsume the current pandemic. “I think we’re in this liminal moment of collectively deciding what we’re going to remember and what we’re going to forget,” says Martha Lincoln, a medical anthropologist at San Francisco State University.

Perhaps that “liminal moment” explains a Guardian headline: “Covid poses ‘greatest threat to mental health since second world war.” In the long run, the crisis may be more about what we did to ourselves than what the actual virus did to us.

Follow Wretchard on Twitter or visit Wretchard.com

Join the conversation as a VIP Member