SPIEGEL editor Jan Fleischhauer describes how, after much soul searching, and making sure no one was looking, he went and ate a McDonald’s hamburger. How the first time he watched a Disney movie it was as a grown up with his own children. He lived in a world where ordinary oranges were regarded with deep suspicion because they might come from South America and where movies were screened for political content. It was universe in which people kept their secret thoughts to themselves; not confiding even with their wives. Presiding over the surface of this planet were two deities, one of darkness and the other of light. “The earlier you decided which side you wanted to be on, the better.” He wasn’t living inside of some cult, unless you call the only world-religion ever indigenous to Europe a cult. He was living inside the Left.

I am part of a generation in Germany that knows no other reality than the dominance of the left. Everyone was a liberal where I grew up. … The way we were supposed to feel about conservatives was obvious. They were either deeply reactionary, because they refused to accept progress, or dangerously narrow-minded. In other words, they were either despicable or pitiful characters. … I don’t remember when it first dawned on me that not all families were like mine. … In Germany, leftists are never truly called upon to justify their views. In fact, their views have become the dominant views, not within the population, which stubbornly adheres to its prejudices, but among those who set the tone and in circles where they prefer to congregate.

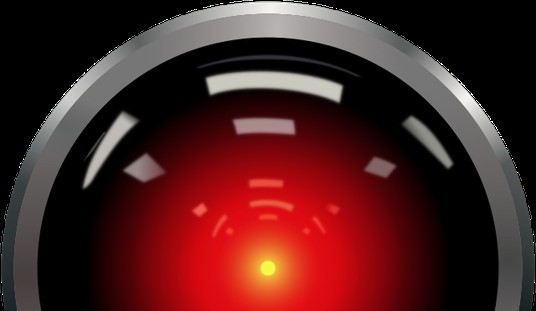

Fleischhauer’s essay “Breaking Ranks” reads like the stereotypical story of a gay man coming out the proverbial closet, except that a gay man had a greater chance of acceptance within his old circle than a man who thought differently from the herd.

Liberals in Germany rave about Obama, fear climate change and the surveillance state, do their best to eat organically acceptable food … Their children attend exclusive schools, even though they are fundamentally in favor of public schools. They like to spend their weekends visiting friends in the country who have been renovating a stone cottage for years — with attention to historical authenticity, of course — and in Italian restaurants they always order in Italian, no matter how well they actually speak the language. …

I don’t know when it happened. There wasn’t a specific day or incident that turned me off to the left. I cannot even claim that I consciously distanced myself. It just happened. Suddenly I no longer found it amusing to listen to constant jokes about the physiognomy of (former Chancellor Helmut) Kohl. I realized that I was relieved when my sons converted the puppet theater my father-in-law and I had built for them into a parking garage. When the discussion turned to the uselessness of marriage and family, I was the one who was secretly rooting for every married couple, hoping it would last as long as possible. Once, at a party, I even dared to put in a good word for nuclear energy during a conversation about climate change. It immediately put a damper on the evening.

Fleischhauer perfectly captures the attraction and curse of living with the herd; it gave you warmth, comfort and support, but at the price of strict loyalty to the tribe, not in any deep intellectual sense, but socially. To step out of the hive meant you were on your own, without a flag, a foreigner in your own country. There might be dramatic scenes of excommunication, even a public shaming, but if you had good friends there would be polite handshakes at the leave-taking and the quiet of retreating footsteps before the silence descended like a blanket.

There were early signs of my tendency, and in retrospect they were clearly recognizable. Fontessa, a friend of mine from school, even claims that she has always known about it. When we talked about our younger days at a class reunion three years ago and I mentioned switching sides politically, she looked at me with pity in her eyes and said: “Jan, you were never truly liberal. It was always just a pose for you.” I felt as if I’d been caught in the act, and yet she didn’t mean it in a bad way. …

We recently invited a couple we have known for a long time, but with whom we had fallen somewhat out of touch, over to our house. He became a law professor at a university in eastern Germany not too long ago, and she promotes golf courses. The conversation quickly turned to the last Michael Moore film, and our friend suddenly claimed that the film could not be shown throughout the entire Midwest of the United States. He made it sound as if Moore were some French auteur filmmaker who was finally holding up a mirror to the Americans, which they couldn’t abide.

I had a pretty clear idea of how the conversation would continue, and I knew that I would be upset with myself afterwards, once again, because I hadn’t challenged him decisively enough. “To make it brief, because we’ll get to this point anyway,” I heard myself saying: “No, I don’t believe that the CIA was behind the Sept. 11 attacks, and yes, we liked living in America.” He was quiet, we drank our tea, and the two said their goodbyes before long. I was shocked by what I had said, but also a little proud of myself.

Maybe at the end of their lives most people find they are one two types: those who never leave home, and those who having once left, return to make it, but a little differently. In some incomprehensible way the long-term survival of the herd depends upon those who wander from it and stare into the edge of the night with wonder and with wariness; with a glance backward in pity and in love at the dancers amid the oranges and flowers.

Secrets of your life

I never wanted for myself

But you guarded them like a lie

Placed up on the highest shelf …

But I, I will never be the same

Oh I, I will never be the same

Caught in your eyes

Lost in your name

I will never be the same

Join the conversation as a VIP Member