Centuries before it was remembered as a day of Independence, July 4 was remembered as one of the most consequential days between the perennial war between Islam and Christendom — and a disaster for the latter. That story follows:

Soon after liberating the ancient Christian city of Antioch from Muslim oppression, the First Crusaders managed to realize their primary goal: take Jerusalem from Islam in 1099.

Despite all the propaganda that surrounds the conquest of Jerusalem, there were very few Muslim calls to jihad (only one is known, and it quickly fell on deaf ears). After all, in the preceding decades, and thanks to Sunni and Shia infighting, local Muslim populations were hardly unused to such invasions and bloodbaths.

In Muslim historian Ibn al-Athir’s words, “While the Franks—Allah damn them!—were conquering and settling in a part of the territories of Islam, the rulers and armies of Islam were fighting among themselves, causing discord and disunity among their people and weakening their power to combat the enemy.”

In this context, the pure doctrine of jihad—warfare against infidels—was lost to the average Muslim, who watched and suffered as Muslim empires and sects collided.

It was only during the reign of Imad al-Din Zengi (d.1146)—a particularly ruthless Turkish warlord and atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo—and even more so under his son and successor, Nur al-Din (r.1146-1174), that the old duty of jihad was resuscitated. They founded numerous madrasas, mosques, and Sufi orders all devoted to propagandizing the virtues of jihad and martyrdom. Contemporary literature makes clear that Islamic zeal (or, in modern parlance, “radicalization”) reached a fever pitch during their reigns.

It was in this context that a Kurd from Tikrit emerged on the scene. Salah al-Din—the “Righteousness of Islam,” or Saladin (b. 1137)—formerly one of Nur al-Din’s viziers, conquered Fatimid (Shia) Egypt in 1171. On his master’s death, he quickly moved and added more Muslim territories—Damascus and Aleppo—to his growing empire, thereby realizing the crusaders’ worst fear: a united Islamic front.

According to his biographer, Baha’ al-Din, Saladin was a pious Muslim—he loved hearing Koran recitals, prayed punctually, and “hated philosophers, heretics, and materialists and all opponents of the sharia.” Above all else he was a devotee of jihad: “The sacred works [Koran, hadith, etc.] are full of passages referring to the jihad. Saladin was more assiduous and zealous in this than in anything else. . . . [H]e spoke of nothing else [but jihad], thought only about equipment for the fight, was interested only in those who had taken up arms, had little sympathy with anyone who spoke of anything else or encouraged any other activity.”

By spring of 1186, Saladin’s empire had so grown that he felt the time was right: “We should confront all the enemy’s forces with all the forces of Islam,” he told a subordinate. Before long, the crusader kingdoms had to marshal all their forces to meet him, near Nazareth in the summer of 1187. Although Saladin had more men—approximately 30,000, half of whom were light cavalry and many of whom were slave-soldiers—the Christians, under the leadership of King Guy, had assembled the largest army since capturing Jerusalem, consisting of some 20,000 knights, including 1,200 heavy horse.

Aware that a head-on assault was futile, Saladin withdrew his forces, went to and besieged the nearby crusader kingdom of Tiberias. Some twenty miles of stony, parched land—with no natural water sources or wells—stood between the crusader army and the besieged city. Nonetheless, on July 3, they set out to relive it.

Looking “like mountains on the march,” a Muslim chronicler remarked that the “hardened warriors” moved “as fast as if they were always going downhill,” despite being “loaded down with the apparel of war.”

On learning that the crusaders had fallen for his trap, Saladin rubbed his hands with glee: “This, indeed, is what we wished for most!” He immediately dispatched his light cavalry to harry the crusaders. Guy hurried the march: the real battle—and water—lay in Tiberias; but when swarms of Muslim archers bogged down his rear force, the king ordered the entire army to halt and fight near a parched and ominous double hill formation, known as the Horns of Hattin.

“This was on a burningly hot day,” writes a Muslim, “while they themselves were burning with wrath.” According to Ernoul, a European squire who was present:

As soon as they [Franks] were encamped, Saladin ordered all his men to collect brushwood, dry grass, stubble and anything else with which they could light fires, and make barriers which he had made all round the Christians. They soon did this, and the fires burned vigorously and the smoke from the fires was great; and this, together with the heat of the sun above them caused them discomfort and great harm. . . . When the fires were lit and the smoke was great, the Saracens surrounded the host and shot their darts through the smoke and so wounded and killed men and horses.

This continued into nightfall. No one slept; from the surrounding darkness, the Muslims, who by now “had lost their first fear of the enemy and were in high spirits,” made a great din. “They could smell victory in the air, and the more they saw of the unexpectedly low morale of the Franks the more aggressive and daring they became.” Out of the smoke-filled gloom and into the crusader camp came volley after volley of arrows, accompanied by cries of “Allahu Akbar” and triumphant iterations of the shahada, the Islamic declaration of faith.

Matters only worsened with the breaking of dawn, July 4: seventy camels laden with water and arrows had arrived to refresh and replenish the Muslim camp; and because Saladin’s archers could now see, even more precise shafts continued to rain on the crusader camp. The sadistic sultan further ordered “water pots placed near the [crusader] camp” and “then emptied in view of the Christians so that they should have still greater anguish through thirst, and their mounts too.”

Trapped like wild animals and driven to the brink of madness, the crusaders charged at their tormenters. And so, to quote Ibn al-Athir:

The two armies came to blows. The Franks were suffering badly from thirst, and had lost confidence. The battle raged furiously, both sides putting up a tenacious resistance. The Muslim archers sent up clouds of arrows like thick swarms of locusts, killing many of the Frankish horses. The Franks, surrounding themselves with their infantry, tried to fight their way toward Tiberias in the hope of reaching water, but Saladin realized their objective and forestalled them by planting himself and his army in the way.

As the battle raged, Muslim reserves “created more brushfires and the wind carried the heat and smoke down on to the enemy. They had to endure thirst, the summer’s heat, the blazing fire and smoke and the fury of battle.” Yet the desperate crusaders fought on: “Terrible encounters took place on that day,” writes another Muslim chronicler; “never in the history of generations that have gone have such feats of arms been told.”

The crusaders, who “burned and glowed in a frenzied ferment,” knew that “the only way to save their lives was to defy death,” and so “made a series of charges that almost dislodged the Muslims from their position in spite of their [greater] numbers, had not the grace of Allah been with them. As each wave of attacks fell back they left their dead behind them; their numbers diminished rapidly, while the Muslims were all around them like a circle about its diameter.”

By now the crusader army consisted of a confused mass of desperate men stumbling over the bodies of their dead; forests of prickly shafts appeared everywhere—in man, beast, and earth. Encircled by an ever-shrinking ring of fire and Islamic horsemen, tormented by arrows and thirst, the Fighters of Christ finally succumbed.

The rout was complete, the gloating great: “This defeat of the enemy, this our victory occurred on a Saturday, and the humiliation proper to the men of Saturday [Jews] was inflicted on the men of Sunday [Christians], who had been lions and now were reduced to the level of miserable sheep,” concluded one Muslim contemporary. In the end, single Muslim soldiers were seen dragging as many as thirty crusaders with one rope, any of whom would once have terrified the same—so maddened with thirst and reduced to delirium were the Europeans.

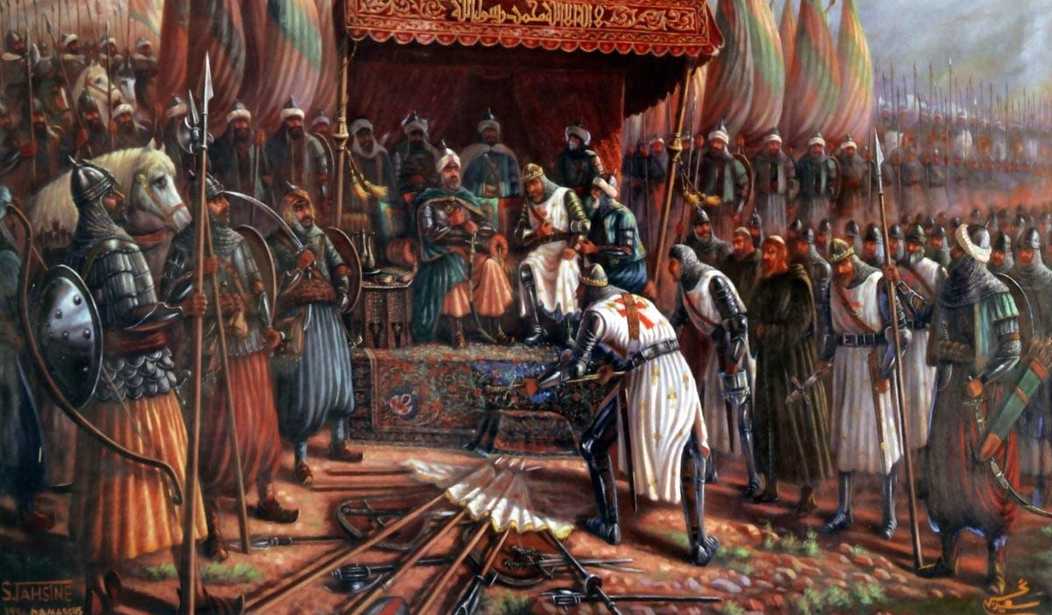

Saladin “dismounted and prostrated himself in thanks to Allah.” Next he ordered the mass slaughter of the military orders—those warrior-monks most committed to the cause, the Knights Templars and Hospitallers: “With him was a whole band of scholars and Sufis and a certain number of devout men and ascetics; each begged to be allowed to kill one of them, and drew his scimitar and rolled back his sleeve. Saladin, his face joyful, was sitting on his dais” as they carved off the heads of their Christian captives.

Then “that night was spent by our people in the most complete joy and perfect delight . . . with cries of ‘Allahu Akbar’ and ‘There is no god but Allah,’ until daybreak on Sunday,” piously concluded a Muslim chronicler.

Finally, adding insult to injury, Saladin had the True Cross—for centuries Christendom’s most revered relic, which was brought by the crusaders to and captured by the Muslims at Hattin—spat upon and dragged upside down in the dirt.

For long, passersby could still see “the limbs of the fallen cast naked on the field of battle, scattered in pieces over the site of the encounter, lacerated and disjointed, with heads cracked open, throats split, spines broken, necks shattered, feet in pieces, noses mutilated, extremities torn off, members dismembered, parts shredded, eyes gouged out, [and] stomachs disemboweled.”

Because so many professional fighting men were lost at Hattin, several vulnerable crusader kingdoms and strongholds were quickly captured by the determined sultan. After a desperate siege that began in September, the holed-upped crusaders even surrendered Jerusalem.

Now “a great cry went up from the city and from outside the walls, the Muslims crying the Allahu Akbar in their joy, the Franks groaning in consternation and grief,” wrote the Muslim chronicler. “So loud and piercing was the cry that the earth shook…. The Koran was raised to the throne and the [Old and New] Testaments cast down,” as Saladin “purified Jerusalem of the pollution of those races, of the filth of the dregs of humanity.”

Muslims appreciated the continuity: “This noble act of conquest was achieved, after Omar bin al-Khattab [the caliph who first conquered Jerusalem in 637]—Allah have mercy on him!—by no one but Saladin, and that is a sufficient title to glory and honor.”

Note: The above account was excerpted from Ibrahim’s Sword and Scimitar: Fourteen Centuries of War between Islam and the West—a book that CAIR and its Islamist allies did everything they could to prevent the US Army War College from learning about it.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member