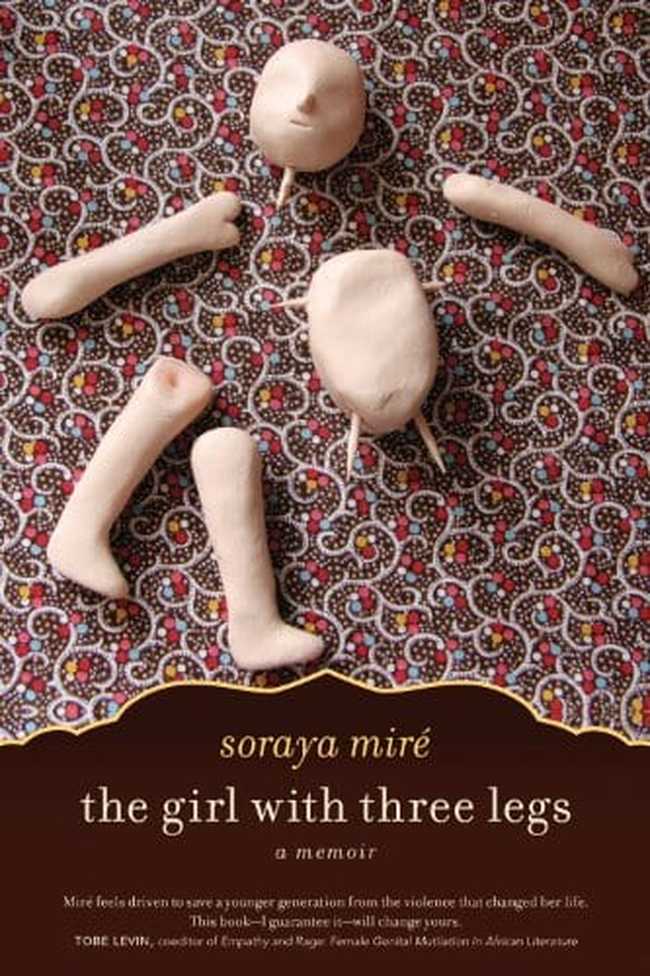

Soraya Miré is a beautiful and talented Somali feminist, a filmmaker, and the author of a new and daring memoir titled The Girl With Three Legs. Soraya lives in Los Angeles and she has the Hollywood-speak down pat. Everyone is “darling,” and “honey,” things are “awesome.” But, through it all, one can still see the Somali African in her. She greets people on the street, café waiters—mere strangers—with warmth and humor, with an easy familiarity, just as if they were clan or tribal members. “What a funny dog! And how are you today?” She wears a strong Biblical fragrance: Frank Incense, a “spiritual body oil,” which I imagine the Queen of Sheba might have worn on her visit with King Solomon. She keeps her main stash in a jeweled, French-African perfume bottle.

Soraya is in the midst of a fifteen city book tour in both the United States and Canada. At a time when travel is far from easy, she cheerfully rises before dawn to catch one early morning flight after another. Soraya patiently sits on the tarmac for hours. A storm delayed her flight to NYC but still, she came, even after she missed her bookstore reading. Soraya flew clear across the country for only two days just to spend some time with me. And, when she left, she flew clear across the country again, this time to Seattle.

Soraya and I first met in Los Angeles many years ago. When her publisher (who is my publisher, too) sent me her manuscript, I literally could not put the book down. And trust me: I have read most of the books on this subject beginning with Fran Hosken’s 1979 The Hosken Report, Nawal al-Sadawi’s work from 1960 right on through the 21stcentury, Alice Walker’s Warrior Marks: Female Genital Mutilation and the Sexual Blinding of Women (1996), Ayaan Hirsi Ali’s Infidel, etc.

Still, Miré’s is a uniquely riveting read. She is a woman who has turned her own suffering into a brave campaign to help other women who have also been genitally mutilated in the Arab, Muslim, and African worlds. Miré is unstoppable. She does not spare anyone: not herself, not her family, not her culture, which persists in traumatizing and torturing its girls in the name of family purity. Miré carefully, personally, exposes how girls are genitally mutilated, usually without anesthesia, always at the insistence of their mothers and/or grandmothers. And she describes exactly how this mutilation leads to lifelong suffering.

Unlike male circumcision, such female genital mutilation means that girls often cannot urinate or menstruate properly. Scar tissue and the sewn-shut vagina lead to agony and serious medical problems. Then, their wedding night becomes a veritable torture chamber as do all subsequent childbirths. (Unbelievably, the post-partum mothers are sewn right back up.) Many develop horrendous fistulas (they lose control of both urination and defecation) and are therefore rejected by the very families who caused this great misery. Miré writes about her own experience of all this—and about her arranged marriage to her first cousin which she fled. (“Today? The man is a drug addict. He has never found a life. And, he never remarried.”)

Miré refuses to give up on—or to stop loving her–family and her people. She tries hard to visualize how her mother was also mutilated before her and also forced into arranged marriages. She shows us how “crazy” women become (hysterical, depressed, anxious, “wild”); and that such torture, especially at the hands of other women, beginning with one’s own mother, can make someone mistrust the universe forever after. But Miré also shows us that suffering can also lead to strength and to truth-telling.

Miré finally has had her mutilation surgically reversed and embarks on a fearless course of sex therapy and psychotherapy. In all innocence, she asks questions that would make the proverbial sailor blush. And she writes about it all.

Next: “The Somali women attacked me more than the men did…”

Soraya has raised funding in order to go on her book tour. She wants to promote the issues raised by her book, the role that women play in enforcing this and other atrocities such as arranged child marriage and arranged cousin marriage — all routinely practiced in the African and Muslim world. Soraya shrinks from nothing. She chose to begin her book tour in Minneapolis where there is the largest concentration of Somalis in America.

“The Somali women attacked me more than the men did,” she tells me:

They said I was against Islam, that I was a poor representative for Somalia. More Somali men, especially young men, are supporting what I’m saying than the women are. Can you believe it?

I suggested that she read my book Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman, which she immediately does. Before she leaves, she begs me for the copy she has begun to read and underline. Well, how can I say no? Still, she is surprised when I tell her that most feminist leaders tried to warn me away from this topic and that despite endorsements from some major feminists, the book has yet to find its audience and is not being taught in Women’s Studies programs.

Soraya responds, “Do you know that none of the leading female experts on FGM and none of the other Somali feminists have helped me? This really hurts. Some promised to write the Introduction to the book or to endorse it but then they all became ‘too busy.’ I do not understand this.”

For years, Soraya performed for no money in Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues; she rubbed shoulders with all the feminist-Hollywood celebrities. She believed that those who are trying to help women would certainly help her.

And then she discovered that the women editors whom her agent approached were all interested in her book—but only if she “prettied it up a bit.”

They wanted me to make it lighter, more elegant, softer. One of the leading feminist presses wanted it ‘prettier.’ That was the word they used. Each publisher who already had one book on FGM or one book by a high profile Somali or Muslim dissident feminist said that they already had that market covered.

Said I: “When I was trying to sell my manuscript about the world’s first female serial killer (the prostituted woman in Florida), many women editors told me that ‘she was not a good feminist role model,’ that ‘she never seems to smile.’ I wonder whether true crime editors have ever expected Jack the Ripper, Ted Bundy, or the Green River Killer to serve as role models for humanity.”

When I became ill I shelved the project.

Next: Soraya fires her agent and finds her new literary home…

Soraya fired her agent and sent an e-mail blast out to editors on her own. Within days, she found Susan Betz at Chicago Review/Lawrence Hill Books who said, “I’ve been waiting for you.”

I am impressed by Soraya’s take charge, can-do spirit. Given her early life, given the nature of her trauma, one might expect her to have given up and given in long ago. But Soraya perseveres. Given the profound challenges of being in permanent exile, of having to live on the edge financially, utterly dependent upon “the kindness of strangers”—she remains a fighter and a survivor. She is more than that. She continues to reach out to her tormenters, to express her love and her desire to remain connected. She is an African. One does not disconnect, Western-style from one’s family. It is, in fact, practically unthinkable.

I am impressed by Soraya’s take charge, can-do spirit. Given her early life, given the nature of her trauma, one might expect her to have given up and given in long ago. But Soraya perseveres. Given the profound challenges of being in permanent exile, of having to live on the edge financially, utterly dependent upon “the kindness of strangers”—she remains a fighter and a survivor. She is more than that. She continues to reach out to her tormenters, to express her love and her desire to remain connected. She is an African. One does not disconnect, Western-style from one’s family. It is, in fact, practically unthinkable.

Although she has changed all the names, Soraya’s female relatives are especially “shamed” and angry that she has exposed them. They are not ashamed of the damage they have done to their daughters, they are not angry about how they themselves have been damaged, they are only ashamed of being held accountable for their daughters’ suffering. They have told Soraya that “You are insulting our family. We will hurt you. Do not come to Canada.”

I tell her: Don’t go to Canada. Or, hire some security, go, read, and return to the States immediately. I am such a Jewish mother. I tell her that she is behaving like an abused child. Soraya instantly says: “Thank you for that. I am going to write that down in my notebook,” and she immediately proceeds to do just that.

She says: “But these relatives, these Somali women, are the ones who are really dishonoring their womanhood. They are (wearing the Islamic Veil), trying to pretend that they are holy women. I told them: ‘I am not cancelling anything. If you try to hurt me, you are the ones who will go to jail.’”

We talk about the recent Somali terrorist kidnappings of Westerners on the border of Kenya and Somalia: two aid workers with Doctors Without Borders, a British tourist and his wife, the French feminist, Marie Dedieu, who was wheelchair-bound from a car accident, and who was slowly dying of cancer. These fiends dragged her off, refused to take along her medication which effectively killed her—and then they tried to ransom her remains to her family. They have been hijacking ships.

Finally: “Now, we are not allowed to cook a certain kind of dish because, when it is prepared and served, it looks like a Star of David…”

“These guys,” Soraya says as we talkabout Somalia’s Al Shabab and Al Qaeda in Somalia, “they don’t own Islam. People are beginning to notice that these religious leaders are drug addicts and hoodlums who are only out for themselves. And, they are raping young girls, raping young boys, kidnapping and brainwashing young boys into Al Shabab.”

Suddenly she tells me this:

In the 1970s, it was forbidden for Somali women to wear the face veil. Now, it is forbidden to be naked faced. Now, we are not allowed to cook a certain kind of dish because, when it is prepared and served, it looks like a Star of David. Now, Somali women are not allowed to wear a bra. But for the last six months, al-Shabab have been feeling girls and women up in the street to see if she is or isn’t wearing a bra.

Soraya is a spiritual woman. She believes that “religion should unite us all. It should be about love. Instead, it has become a way of war.”

Now, Soraya is focusing on the women, the survivors of FGM:

How can they continue without stopping to deal with their own pain? How can they make a better life for their children if they don’t try to heal? Mothers have got to raise both their boys and their girls differently. The issue of FGM is about the abuse of children. Early on, a Somali woman exposed this in a book titled Sisters, Why Do We Weep? but few heard of her work or understood why she had been kicked out of Somalia. She was exiled to Sudan. She came before Fran Hosken, an Austrian-American Jewish woman who was treated pretty badly by my African sisters for having the nerve to expose our pain and our shame.

Soraya’s book is about an immigrant woman in exile, about someone who once lived a very luxurious life but who gave it all up for the sake of freedom and dignity. The book is also an ode to female courage and healing against high odds and about the high cost of that courage which includes being ostracized, death-threatened, impoverished, and treated as a “crazy” woman when she is at her sanest and most heroic.

May God bless this woman with continued health, sanity, and generosity, and may she herself guard and preserve the shining spirit of love and forgiveness with which she is already blessed .

*******

Join the conversation as a VIP Member