According to Pew Research, Gen Z consists of everyone born between 1997 and 2012. How “they” arrived at that time period is a mystery, and frankly, I don’t much care how or why they picked that date range to define a generation of snowflakes.

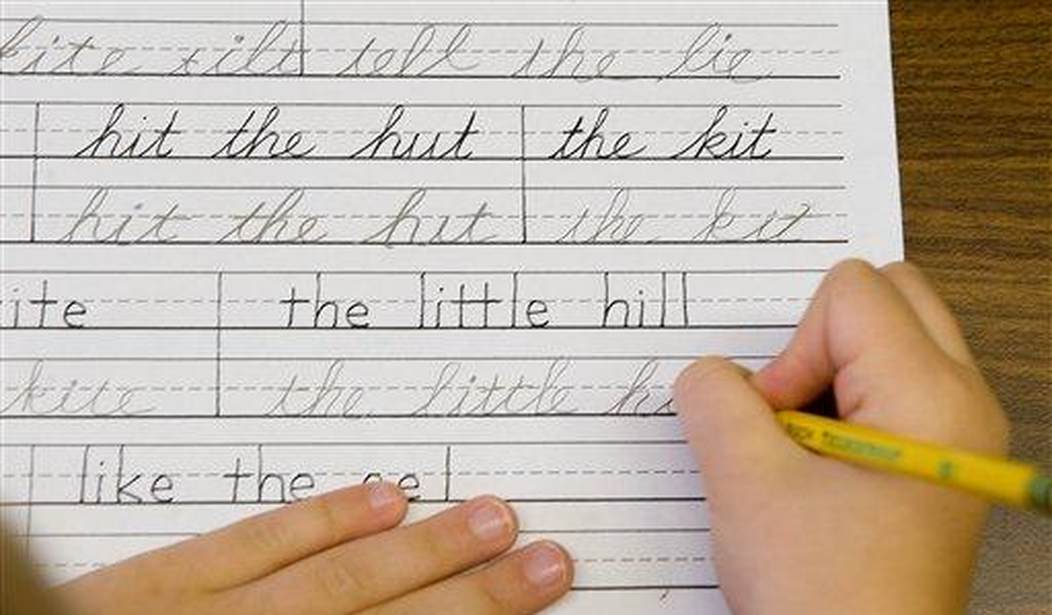

After learning this, I hate them even more: Generation Z never learned to write in cursive.

That’s a tragedy, since there is no more achingly beautiful form of the English language than a love letter written in what we used to call “longhand.” There is something so magnificently personal and private about writing how you feel about that special someone using whirls and loops in ink from an old-fashioned fountain pen.

Even more catastrophic is that Gen Z never learned to read cursive. And therein lies a tale of lost civilized behavior that may never be recovered.

With the development and prominence of technology, cursive has become increasingly obsolete, but what impact will this have for the future?

According to The Atlantic, this means, “In the future, cursive will have to be taught to scholars the way Elizabethan secretary hand or paleography is today.” This directly impacts archival work. Many written documents from the 19th century and other early time periods are written in cursive. While it was once taken for granted that American students would know how to read cursive, now that cannot be the case.

Archival work largely depends on a reader’s ability to read hard-to-read texts in shorthand and/or cursive. Will this mean that universities will start having to offer college courses in history programs on how to read cursive? Only time will tell.

The villain in this tale of the evil destruction of a treasured way to communicate is Common Core. And with most records stored in cursive, it begs the question of who is going to read about the past if it’s only available to a select few who can read cursive?

Drew Gilpin Faust who wrote in The Atlantic about the loss of cursive told NPR that the loss of cursive means that “the past is presented to us indirectly.”

Using the example of a contract, Faust said to NPR, “I mean, just imagine if you had some kind of contract that you had signed and you couldn’t read it and someone told you, well, this is what’s in the contract. That’s what’s in the contract. And then later you might find that it was something else. So there are limits in your power, in your sense of how the world works and your sense of how the world used to work when you can’t have access to a means of communication.”

“On team cursive, advocates point to the many studies that have shown that learning cursive not only improves retention and comprehension, it engages the brain on a deep level as students learn to join letters in a continuous flow,” Cindy Long said in an article for National Education Association. “It also enhances fine motor dexterity and gives children a better idea of how words work in combination.”

The same holds true for reading a damn book instead of listening to it. You can’t hear the author’s voice when someone else is reading a book to you. And engaging the brain on that “deep level” invites the imagination to take hold and propel the reader to places no audiobook could ever take you.

Related: Moms Who Objected to CRT File Suit After Being Harassed by School

I suppose I shouldn’t complain about the death of cursive writing. No one can read what I write, either — a skill for which the good Sisters of Mercy rapped my knuckles many times. But along with the progress of being able to read the block printing on computer monitors much more easily, the loss of cursive writing is a disappointment that I will have a hard time getting over.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member