“You’re a Republican? But… you’re not racist!”

My friend’s reaction to finding out that I am a Republican surprised me. We had been acquainted for a few months, but our conversations had gone no deeper than in-class discussions and pleasantries. Personal politics hadn’t come up. But now she had heard that I was involved with the College Republicans at Kansas State University.

Although shocked by my friend’s cross-labeling of Republicans and racists, I knew such labeling goes both ways. The Right uses terms like “snowflake,” for example, to reduce a political worldview into a single word (even if “snowflake” avoids unfairly linking political opponents to the Ku Klux Klan).

Today’s style of political interaction, characterized by assuming the worst of one’s opponent, signifies the loss of something vital in our nation. We have forgotten how to debate; now, we just argue.

Debates have been essential to democracy since America’s founding. The peaceful exchange of conflicting ideas signifies an informed citizenry, a key component of any healthy democracy. Debate is an art befitting free persons. The loss of this art foreshadows a loss of freedom. As Jill Lepore of The New Yorker wrote, “Etymologically and historically, the artes liberales are the arts acquired by people who are free, or liber. Debating, like voting, is a way for people to disagree without hitting one another or going to war.”

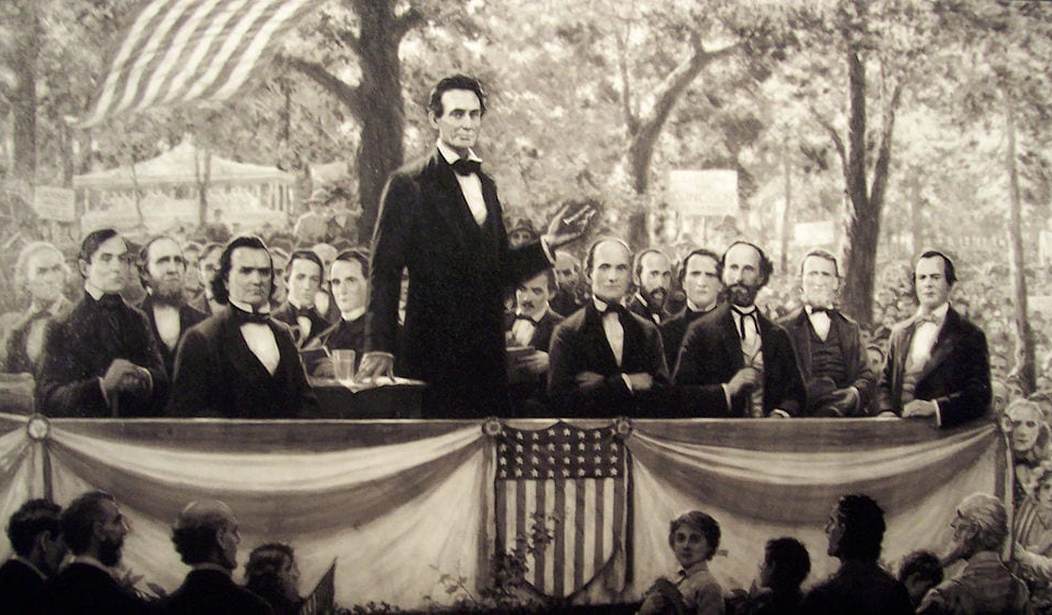

One haven for this lost art is the Lincoln-Douglas Value Debate. Based on the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates themselves, its style asks debaters to identify underlying values in order to answer questions like, “Do governments have a moral obligation to assist other nations in need?” and “In the pursuit of justice, should due process or the discovery of fact be valued higher?” We should take a lesson from Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas. Despite examining heavy issues like slavery, they maintained a professional and idea-centered discourse.

The lessons learned from debating “LD” don’t end with the debate round. The LD framework helps current and future voters discuss current issues and, ultimately, search for truth. Debate requires us to step outside of ourselves, detach our opinions and ideas from our identity, and collaborate with our opponents to gain a new understanding of the topic at hand. Here are a few tips to accomplish this, whether you want to improve your formal debate skills or just avoid doing the same political labeling you hate being done to you:

1. Read some philosophy

Peter Hitchens, the English journalist and author, wrote, “Is there any point in public debate in a society where hardly anyone has been taught how to think, while millions have been taught what to think?”

You don’t necessarily have to dust off John Locke’s Two Treatises on Government per se, but you could do worse. Reading any Enlightenment thinker important to the American founding is helpful for understanding the basics of how the best and brightest thinkers have attempted to answer timeless questions about the purpose of government and how it should interact with the citizenry.

2. Avoid personal attacks

“Insults are the arguments employed by those who are in the wrong,” Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote. Attacking the man, instead of his method, is a popular but poor form.

Recognizing that another person’s argument is not inherent to him or her, and that your argument is not inherent to you, allows the debate to become productive. It shifts your focus from attacking one another in ad hominem fashion to a discussion of truth and how to best pursue it.

3. Identify values

Mark Twain said that “facts are stubborn, but statistics are more pliable.” Examples and statistics are helpful but should be used only to illustrate, not prove an argument. Statistics can be found for almost any argument. What’s important are the values that guide our opinions and arguments.

Values underpin every decision we make, from how to respond to a foreign policy crisis to what to have for lunch. It’s vital to recognize and name them in a debate.

For example, the question might be whether it’s better to eat a salad or a cheeseburger for lunch. It’s hard to compare these choices unless you understand what you value most. Is being healthy your goal? Or is “tasting good” your main criteria? Whatever your answer is, that’s what you value. Your value becomes a measuring tape for deciding which meal to choose.

In politics, as in life, values are where the real debate is. Sometimes, ideological opposites hold the same value but approach it in vastly different ways. But as long as we remain in the weeds of the argument, not realizing the common ground we have, a productive solution will be difficult to reach.

4. Pursue truth

Ultimately, the goal of debate is to reach a better understanding of the truth and walk away from a discussion with a new perspective of another person and his or her point of view. (Or is that the goal? It depends on your values…)

Discussions of sensitive topics like sexuality, science, and morality aren’t easy. But they are necessary. We can argue about them all day, but we will not truly resolve any of our disagreements until we have relearned the all-but-lost art of debate.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member