This is the second in a two part article. Read Part One, Where Kurdistan Meets the Red Zone, here. Scroll down for video.

KIRKUK, IRAQ — Kirkuk, like Baghdad, is one of the most dangerous places in the world. Car bombs, suicide attacks, shootings, and massacres erupt somewhere in the city every day. It is ethnically divided between Arabs, Kurds, and Turkmens, and is a lightning rod for foreign powers (namely Turkey at this time) that interfere in the city’s politics in the hopes of staving off an ethnic unraveling of their own.

The city’s terrorists are mostly Baathists, not Islamists, and their racist ideology casts Kurds and Turkmens as enemies. They’re boxed in on all sides, though, and have a hard time operating outside their own neighborhoods. In their impotent rage they murder fellow Arabs by the dozens and hundreds. They have, in effect, strapped suicide belts around their entire community while the Kurds and Turkmens shudder and fight to keep the Baath in its box.

Kurdish and Turkmen neighborhoods are safer than the Arab quarter, but the city is out of control. Car bombs can and do explode anywhere at any time.

Kirkuk, Iraq

I spent the day with Peshmerga General “Mam” (Uncle) Rostam and Kirkuk’s Chief of Police Major Sherzad at a house Mam Rostam uses a base in an old Arab neighborhood that now belongs to the Kurds. Just after lunch Major Sherzad’s walkie-talkie began urgently squawking.

Kirkuk Police Chief Major Sherzad answers a call from the station

“There has been a shooting,” he said. “Two men on a motorcycle rode down the street and fired a gun at people walking on the sidewalk. One of the men was apprehended. They are bringing him here.”

For some reason I assumed when the chief said “here” he meant the police station. He did not. He meant Mam Rostam’s.

“They will be here in two minutes,” the chief said.

“Here?” I said. “They’re bringing him here? To the house?”

“They will bring him here before taking him down to the station,” he said. “I’ll interrogate him here. I’m not going to feel good until I slap him.”

An Iraqi Police truck pulled up in front of the house and slammed on the brakes.

“Here he is,” the chief said.

I grabbed my video camera, flipped the switch to on, and ran out the door.

Both Major Sherzad and Mam Rostam slapped the suspect around, rifled through his personal items, and discovered the astonishingly stupid excuse he and his friend had for shooting at people — an even dumber excuse than if they had been political terrorists.

It was a strange and surprising interruption in the middle of a relaxed interview — basically an episode of Cops in Iraq.

Watch the video. Don’t continue reading until after you’ve watched the video.

qaraf3COnEY

The suspect was taken down to the station. Chief Sherzad went down there to interrogate the shooter — assuming the shooter actually turned himself in. Mam Rostam, my colleague Patrick Lasswell, our translator Hamid Shkak, and I returned to the porch and sat again in our plastic chairs.

“Where were we?” Mam Rostam said, as though nothing important had happened and we could return to our interview now. What else was there to talk about, though, aside from what had just happened? I still wasn’t sure who this guy was and why he and his friend were shooting at people.

“Those guys are not terrorists,” Mam Rostam said. “But they are troublemakers, young people messing around in the town. But we have to seize them and investigate them to find out why they are doing this. People think there are terrorists and that we are not taking care of it.”

“Well, what happened exactly?” I said. I obviously did not yet have an English-language transcript of the video. Our translator Hamid couldn’t hear everything that was said during the interrogation. “What makes you say he is not a terrorist? He was shooting at people.”

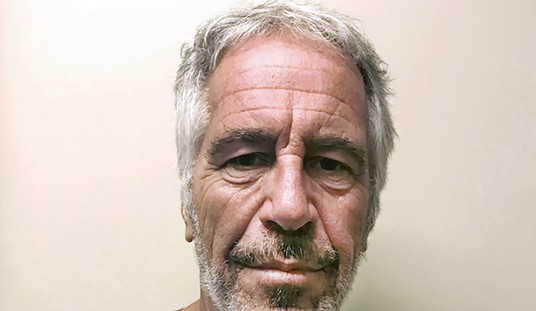

Peshmerga General “Mam” Rostam

“This guy’s identification card in his clothes, in his luggage, shows that he belongs to the Kurdistan Democratic Party,” Mam Rostam said. “That doesn’t necessarily mean he’s not a terrorist, but he’s not a stranger, he’s from the city, he’s known by people who work with the Peshmerga [the Iraqi Kurdish army]. But there are still some questions to be answered as soon as we capture the other guy.”

“You hit him very exactly, it seemed,” Patrick said. “You knew exactly how hard to hit him. His face wasn’t damaged. I would have broken his nose.”

Mam Rostam laughed. “He still seems like a teenager,” he said. “We have to fight them a little bit, to teach them not to do dangerous things, just to stop them where they are. They need to be adjusted more than they need to be punished. So we’re trying this stage with them first. If it doesn’t work, then there is another issue.”

“His teeth were still intact,” Patrick said.

Mam Rostam laughed again. “Those slaps were advice,” he said. “Because the city is unstable, we have to be a little bit violent with people to stop them. Otherwise they won’t be afraid to do many other evil actions. We have to be a little bit severe.”

Everything in Kirkuk is severe.

“What do you think is going to happen in Kirkuk if the United States withdraws from Iraq next year?” I said, wondering if the city would become much severe very quickly.

“It will not be good,” Mam Rostam said. “Not for Iraq and especially not for Kirkuk. At a minimum there will be trouble with the neighbors, with Turkey and Iran. They will interfere.”

“They will interfere in Kirkuk in particular?” I said.

“Especially in Kirkuk,” Mam Rostam said. “Turkey is always interfering. But I believe the U.S. won’t leave Iraq until 2025. That’s my guess.”

“Even in 2025,” Patrick said, “you will ask us to stay longer for tea.”

Really. It’s hard to extract yourself from any kind of social event in the Middle East without being ordered to drink yet another tea.

“If America pulls out of Iraq, they will fail in Afghanistan,” Mam Rostam said.

Hardly anyone in Congress seems to consider that the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan might become much more severe if similar tactics are proven effective in Iraq.

“And they will fail with Iran,” he continued. “They will fail everywhere with all Eastern countries. The war between America and the terrorists will move from Iraq and Afghanistan to America itself. Do you think America will do that? The terrorists gather their agents in Afghanistan and Iraq and fight the Americans here. If you pull back, the terrorists will follow you there. They will try, at least. Then Iran will be the power in the Middle East. Iran is the biggest supporter of terrorism. They support Hezbollah, Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and Ansar Al Islam. You know what Iran will do with those elements if America goes away.”

I seriously doubt Iran would actually nuke Israel, as many fear, if the regime acquires nuclear weapons — although I’ll admit I’m a bit less certain of that than I am of, say, Britain and France not nuking Israel. The Iranian regime, most likely, wants an insurance policy against invasion and regime change. The ayatollahs will then be able to ramp up their imperial projects in Lebanon, Iraq, and the Gulf with impunity.

“Is Iran doing anything here with the Shia Arabs in Kirkuk?” I said. When Saddam Hussein ethnically cleansed Kurds from portions of Kirkuk he replaced many of them with Shia Arabs from Najaf and Karbala that he wished to be rid of. “And what about Moqtada al Sadr? Does he have a presence here?”

“Officially and obviously, no,” Mam Rostam said. “Neither the Iranians or Moqtada al Sadr exist here at all as far as we know. They might be here secretly. They probably are. But there is nothing official or apparent.”

Our encounter with the young punk of a Kurd notwithstanding, most of the violent troublemakers in Kirkuk are Arabs. Most of the victims of violence are Arabs, as well. While sitting a kilometer or so from Kirkuk’s Arab quarter I felt physically repulsed from the area. Going there without serious weapons and armor would be suicidal. What about average Arabs, though, in Kirkuk? They can’t all support the Baathists and Islamists.

“What do the Arabs who live here think of you?” I said to Mam Rostam. “And I mean the civilians, not the terrorist groups.”

General Rostam is well-known in Iraq as a formidable military leader and a genuine bad ass. His body is covered with battle scars, but he’s damn near invincible. He’s the last guy you want on your case if you work with Al Qaeda or the Baath.

Major Sherzad (left), local tribal leader (center), Mam Rostam (right).

“I have good relations with them,” Mam Rostam said. “They come over to the house. Last time some of the Arab tribal leaders came over I took them to our headquarters in Suleimaniya. We enjoy our relations with them. We have no difficulties with them and no differences in our opinions.”

Don’t be surprised by his statement. Obviously he’s exaggerating to an extent. Somebody in that quarter doesn’t agree with his opinions or there wouldn’t be car bombs. But it’s only logical that a typical Arab in Kirkuk wishes to see an end to the insurgency and the terror campaign. Why wouldn’t they? Most of the bombs explode in their neighborhoods. Some of them kill hundreds of people. If the Kurds of Kirkuk live in fear of the bombs, imagine how most of the more-endangered Arabs must feel.

*

It was the end of the day and time for Patrick, our translator Hamid, and I to head back to the sanctity of the Kurdish autonomous region. There are no hotels in Kirkuk, and it would have been madness to spend the night in one if there were. Last year a reporter and a photographer from National Geographic were issued death threats by cell phone mere hours after they arrived in the city.

The three of us said our goodbyes to Mam Rostam after we finished our last glasses of tea. He told me to visit him again if I find myself in Kirkuk in the future while embedding with the American military.

“Do you know a safe way out of the city?” I said to Hamid, who was designated as permanent driver. “This is not the kind of place where we want to make a wrong turn and end up in the wrong neighborhood.”

Hamid Shkak, driver and translator

We had nothing to worry about. Mam Rostam sent some of his men to guide us out of town in a convoy.

I kept snapping pictures on the way out. Kirkuk is unspeakably ugly. I felt gloomy and depressed just driving through in a car. It’s hard to believe people live in places like this and have to put up with its problems. The northern Kurdish cities of Dohuk, Erbil, and Suleimaniya are ramshackle and haywire compared with American cities, but they look like lovely Italian hill towns compared with Kirkuk. Perhaps it’s no surprise that some half-baked and immature individuals take to shooting at people on thrill rides to relieve the pressure.

A typical view of Kirkuk, Iraq, in the central government region

A typical view of Dohuk, Iraq, in the Kurdish autonomous region.

“If the Los Angeles chief of police were caught slapping a suspect on video,” I said to Hamid as he drove, “he would likely be fired.”

Hamid bristled with annoyance. “Do you think American police officers could handle a city like Kirkuk?”

Actually, yes. I thought of that famous line in Casablanca when the German Major Strasser asked Rick, Humphrey Bogart’s character, if he could imagine Nazi troops in New York. “There are certain sections of New York, Major, that I wouldn’t advise you to try to invade.”

But that’s not the real reason. The real reason is that no American officers would join the Baath or Al Qaeda. Far too many officers do in Iraq, which makes a secure environment nearly impossible.

“I don’t mean it as a value judgment,” I said to Hamid. “That’s just how it is. Americans don’t tolerate police violence, even against someone who might deserve it. And yes, I think American police could handle a place like Kirkuk. At least we can be certain the police won’t defect and side with the terrorists, as they often do there.”

We arrived in Erbil, the capital of safe and autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan, in less than an hour. Central government territory is just a few minutes drive south of the city. It’s surreal that Erbil suffers no terrorism while Kirkuk explodes every day. There is no formal border between them, and you could ride a bicycle from one to the other in just a few hours.

There might as well be a border between them. I visited Iraqi Kurdistan four times in fourteen months. But I never felt like I’ve been to Iraq until I went to Kirkuk.

Iraq isn’t a country. It is a geographic abstraction.

Post-script: Patrick Lasswell also wrote about the police smackdown in Kirkuk, and he spent more time on that subject than I did.

Post-script: If you like what I write, don’t forget to pay me. Travel in Iraq is expensive, and I am not able to do this job without your financial assistance. If you haven’t donated before, please consider donating now. If you have donated before (and a thousand thanks for doing that), please remember that my expenses are ongoing and my donations need to be ongoing too.

[paypal_tipjar /]

(Email address for Pay Pal is michaeltotten001 at gmail dot com)

If you would like to donate money for travel and equipment expenses and you don’t want to use Pay Pal, please consider sending a check or money order to:

Michael Totten

P.O. Box 312

Portland, OR 97207-0312

Many thanks in advance.

All photos and video copyright Michael J. Totten

Join the conversation as a VIP Member