How or why children develop disorders such as anxiety or depression is a topic that many parents and psychologists alike hope to better understand. A recent study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (JAACAP) might be able to shed some light on the subject.

The researchers found that “early indicators of anxiety and depression may be evident in a newborn baby’s brain.” This finding is significant because it tells us that brain structure can be responsible for the eventual development of anxiety and depression in children (rather than these disorders causing a change in the brain).

Initially when the researchers began the study, they were examining the differences in brain connectivity between full-term babies, and those born at least 10 weeks premature (since the latter group tends to be at a higher risk for developing mental disorders later in life). PsychCentral discusses the findings:

“The fact that we could see these connectivity patterns in the brain at birth helps answer a critical question about whether they could be responsible for early symptoms linked to depression and anxiety or whether these symptoms themselves lead to changes in the brain,” said Cynthia Rogers, M.D., an assistant professor of child psychiatry. “We have found that already at birth, brain connections may be responsible for the development of problems later in life.”

[…]

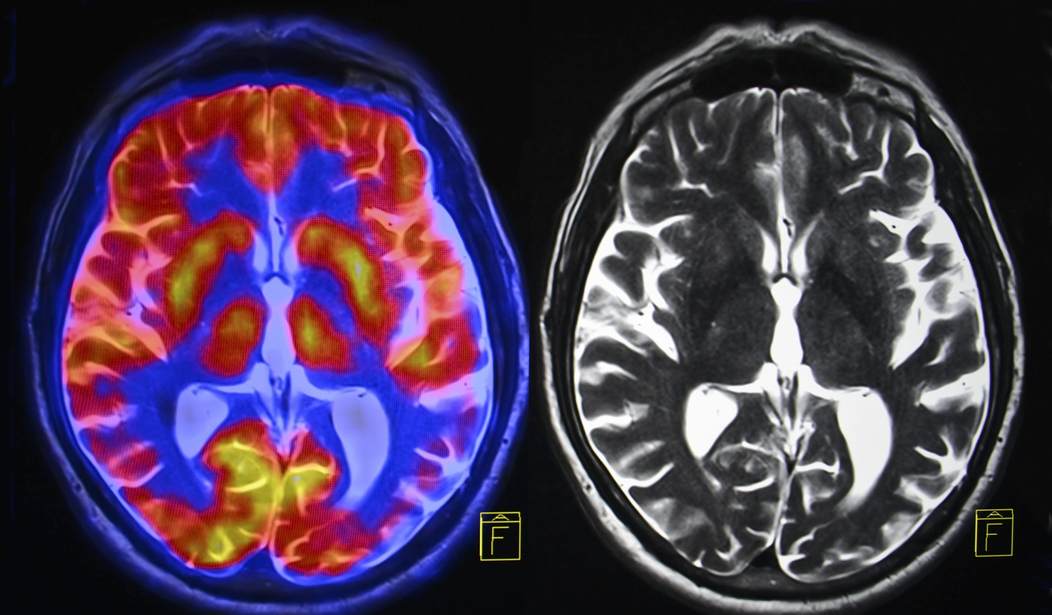

The findings reveal that connectivity patterns between the amygdala and other regions of the brain in healthy, full term babies were similar to those found in adults. Although there were similar patterns of connectivity in premature infants, the strength of their connections between the amygdala and other brain regions was decreased.

Furthermore, connection patterns between the amygdala and other structures — like the insula, which is involved in consciousness and emotion, and the medial prefrontal cortex, which plays roles in planning and decision making — were associated with early symptoms related to depression and anxiety.

When the researchers gathered subsets of the two groups of babies for a follow-up at two years of age, there was no early sign that the premature babies were more likely to develop depression. But other factors might have come into play, including the socioeconomic and mental health background of the parents of the full-term babies. In the event that the researchers’ grant is approved, they will be able to observe the children when they are closer to ten years old in the hopes of finding something more conclusive on the matter.

Nonetheless, the discovery of brain structure differences in newborns is significant in and of itself and can open the door for new approaches to treating children who are showing early signs of anxiety and depression.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member