“It is impossible for those outside of literature departments to understand how weird such departments have become. You can see the evidence from without, but only within can you drink deep of our Stalinism Lite.” — Prof. Scott Herring, in Exiled.

Investigations of academia by David Horowitz, Bruce Bawer, and the California Association of Scholars have all pinpointed the massive shift to the left — and the corresponding decline in scholarly rigor and balance — that has occurred in the professoriate at North American universities. More such studies are needed, for the takeover of higher education has in many cases been almost entirely unimpeded and even unnoticed or denied — or made to seem natural and unintentional. Liberal academics, priding themselves on their tolerance, routinely downplay conservative concerns about bias, claiming that the leftist influence is exaggerated or has already passed its peak. Where leftist dominance is admitted, it is claimed to be the innocent result of career self-selection: liberals are, according to the common wisdom, more intellectually curious and creative than conservatives, and therefore naturally drawn to the academic life, just as conservatives — rule-bound and money-obsessed — are naturally drawn to business, police work, or engineering. If leftists do dominate, so the story goes, their presence is benign.

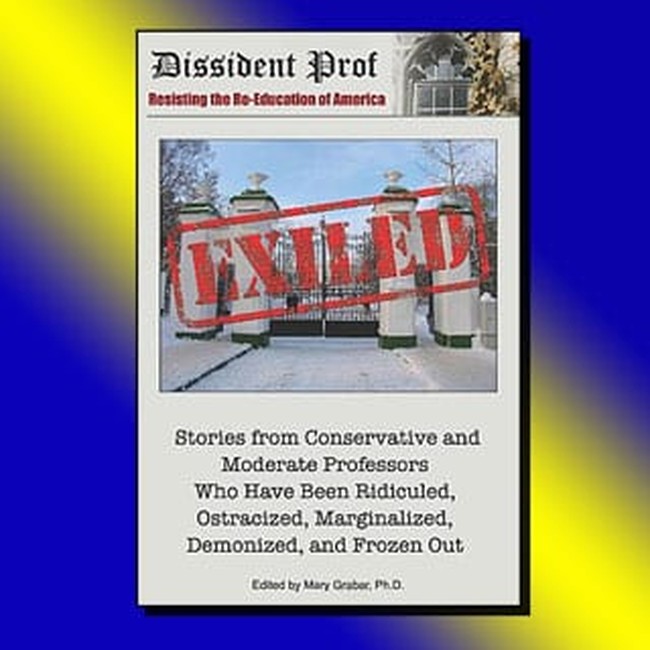

A new book edited by Mary Grabar paints a much darker picture of academic life, showcasing the overt and covert ways that conservative intellectuals are marginalized or excluded. In a series of witty and engrossing narrative essays with the deliciously cheeky title Exiled: Stories from Conservative and Moderate Professors Who Have Been Ridiculed, Ostracized, Marginalized, Demonized, and Frozen Out, the collection provides first-hand accounts of what happens to those who flout the protocols of correct belief or pursue research outside the parameters of approved scholarship. They are indeed “exiled,” if not from academia itself — though some are — then at least from the company of the blessed in their departments and research communities. The pains of such exile range from personal shunning to insurmountable career roadblocks, but worst of all, perhaps, to the recognition that propaganda is being disguised as knowledge in thousands of university classrooms.

The animating spirit behind this collection, Mary Grabar, is an academic and writer, contributor to various conservative journals and electronic forums (including PJ Media.com), and the bold, always-interesting creator of Dissident Prof Press and website. Her blog covers everything from the agenda of the Common Core public school curriculum to the conservative message in The Killing Fields and much else; she writes in an impassioned and no-nonsense style. Horrified by attempts to destroy the traditional literary canon and to remake English studies as an anti-Western (and anti-intellectual) project, she has become an indefatigable critic of progressivism in all its guises. Her introductory and concluding comments in Exiled, in which she denounces the takeover of the academy by thuggish ideologues and pinpoints their sloppy logic and faulty assumptions, are characteristically bracing and informative. The essays she has gathered form a compulsively readable collection illuminating how the leftist bias in academia manifests itself and why it matters.

Forms of academic heresy are manifold. As humorously detailed in the chapter of Exiled titled, “The Most Sacred Part of Them: Professors Behaving Badly,” M.D. Allen entered the outer darkness quite unintentionally. A new professor of literature eager to find his professional feet, he thought he was affirming his progressive credentials when he presented a paper on two English women travel writers at an annual literary conference; because he failed, however, to adopt the mandatory tone and approach to the subject, he was deemed not only inadequate but “offensive” and morally obtuse. From that point on, as he discovered, his attempts to dissent civilly from the tendentious drift of his discipline were met with the kind of open hostility and contempt reserved for the irredeemably odious. Allen ends by reflecting astutely on the forms of (frustrated) religious zeal that leftist persecution embodies. Martin Slann, in “Losing Friends and Dining Alone,” knew full well what he was getting into when he began to disagree publicly with “the doctrine of moral parity” that leftists have instituted for discussion of Islam amongst political scientists. His conference presentations on the moral bankruptcy of the United Nations and the incompatibility between Islam and political democracy produced outraged reaction from audience members and desertion by once-friendly colleagues. The realization that some academics are bigots has not, he avers, bothered him as much as the knowledge that “these same people are teaching hundreds of students each year to embrace a grotesque combination of Islam, Marxism, and contempt for democratic values.” Slann finds compensatory satisfaction in updating a textbook of his own that identifies the totalitarian elements of Islam.

Paul Kengor, in “Anti-Anti-Communism and the Academy,” takes a less personal approach to his experience in political studies, turning the lens on anti-communist scholars Richard Pipes and Vladimir Brovkin, who encountered the determined disbelief of other researchers. Linking individual marginalization to widescale pedagogical bias, he demonstrates how liberal disdain for anti-communism — even amongst those who are not Marxist radicals themselves but nonetheless harbor a loathing for conservatives — has led to a whitewashing of Communist atrocities and socio-economic failure. The effects are, he points out, catastrophic for Americans, who as a result of biased teaching are “not only ignorant of communism but prone to support far-left economic policies or to elect people who have been mentored by communists, have links to communists, or subscribe to forms of socialism.” His analysis of the glaring omissions and inaccuracies in textbooks’ accounts of the Cold War, through which generations of young people have been taught to misunderstand the most decisive ideological battle of the twentieth century, makes for sobering reading.

The last three essays are by scholars who completed PhDs but did not find tenured positions in their disciplines; they write with varying degrees of equanimity or chagrin about the realizations and accommodations they reached. Scott Herring, in “Stalinism Lite,” recognized early on that he would never be able to toe the multiculturalist party line with students in his English classes. He ultimately gave up the liberal pretense, grateful to be able to teach writing to advanced science students in a University Writing Program. Brian Birdnow, in “‘C’ for Conservatism, the New Scarlet Letter,” recounts how all his worst fears about completing a doctorate in a liberal-dominated History discipline were confirmed by his professional struggles. His book manuscript on the Communist Party of Missouri was repeatedly refused publication by biased university presses, and he had the unpleasant experience of witnessing the takeover of his discipline by social historians, who edged him out of the job market and turned him into a “non-person.” In “The Creed of Political Correctness,” Jack Kerwick shows how he came to see that his cherished idea of the university as a forum for the free exchange of ideas was “a fiction of the first order,” in a discipline (Philosophy) obsessed with pious utterances about social power, and in which intellectual curiosity and civil debate are almost non-existent. The sense of loss — not only of career opportunities but of an ideal — is palpable in all three of these cogent and absorbing analyses.

Despite Herring’s claim that “reality” will ultimately trump “ideology,” there are few rays of light here. Far from dwindling in significance and power, leftists seem firmly in possession of the ivory tower. They have been remarkably successful in transforming once-substantial academic subjects into programs of indoctrination: students learn a turgid theoretical language enforcing a simplistic and misleading worldview in which a band of heroic victims — the transgendered, the racialized, the othered — struggle against their white male oppressors. Everything that has gone before in western culture, including its democratic institutions, civilized codes of conduct, and traditions of difficult freedom, are dismissed as remnants of a fascist past while a moratorium is strictly enforced on criticism of Islam or communism. Professors who are openly unorthodox in their teaching and research are rarely hired, and the few tenured heretics able to speak out are for the most part acutely aware of their isolation. Under such circumstances, there is small hope for immediate change: anger-fuelled individual resistance, resigned irony, or humorous refusal to conform — and the will to write about them — are perhaps the best responses we can hope for, and all are robustly on display in this marvelous collection.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member