Two days ago, I wrote in this space on Sunday's debacle in Los Angeles, at which pro-Palestinian (read pro-Hamas, pro-murder, pro-hostage-taking, pro-rape) demonstrators shut down access to the Adas Torah Synagogue in the heavily Jewish Pico-Robertson neighborhood. LAPD officers were slow to respond and ineffectual when they did respond, leading to speculation on social media that they were ordered to stand down in the face of pro-Palestinian provocation.

One should always be reluctant to ascribe to malice anything that can be explained by incompetence or inexperience, so, absent any credible report that someone did indeed order the police to stand down, I will continue to believe that when trouble broke out at the synagogue on Sunday, the LAPD was caught unprepared and unable, not unwilling, to quell the violence.

I didn't witness the incident, nor have I spoken with anyone present, so what follows is pure speculation, albeit based on more than 40 years in law enforcement, more than 30 of it with the LAPD. The first thing to keep in mind is that in the LAPD, Sundays are the least busy days of the week and therefore the most lightly staffed. What's more, the officers who are on duty on Sundays are often the least experienced, this owing to the fact that officers higher in seniority are given preference in selecting days off and that most of them choose to be off on weekends.

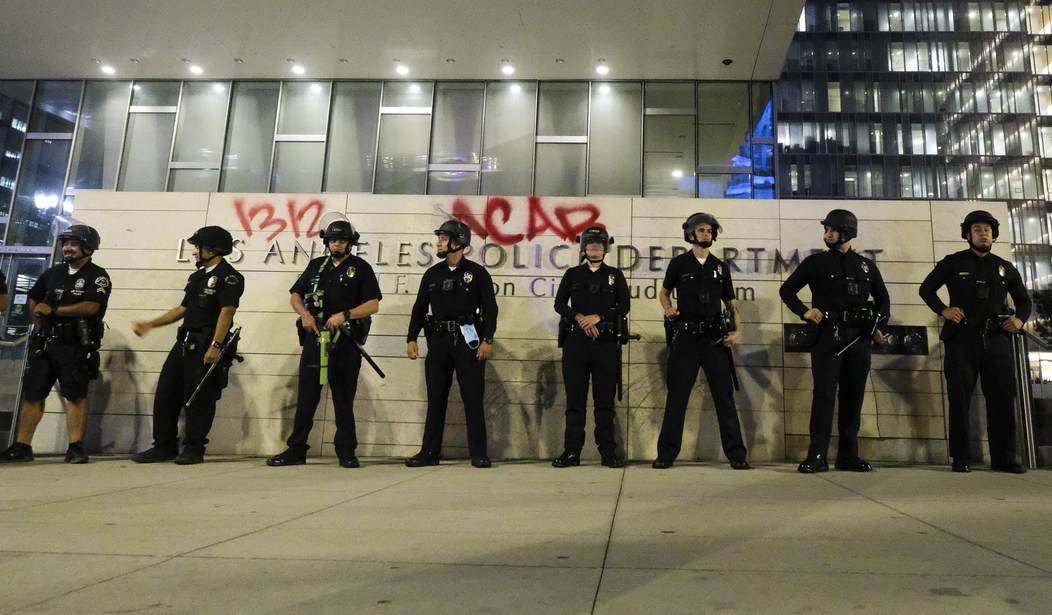

My speculation is supported by viewing video clips from the scene like this one, in which most of the officers' serial numbers are displayed on the back of their helmets. The higher the number, the newer the cop, and most of the officers depicted in this clip are pretty green.

What's more, the West Los Angeles Division is home to about 230,000 people spread across 64 square miles, yet patrolling the area on Sunday were probably no more than 16 officers and a sergeant or two. This crew would have been overseen by a watch commander back at the station, either a lieutenant or senior sergeant. Few if any of these officers would have had any significant training in crowd-control techniques. Both captains assigned to the station, the patrol commanding officer and the area commanding officer, would have been off duty (not that their presence would necessarily have helped).

In short, the available personnel at West L.A. Division were unable to contend with the situation at hand, necessitating the drawing of resources from the other divisions in the LAPD's West Bureau, Wilshire, Hollywood, Olympic, and Pacific, all of which would have had staffing and experience issues similar to those seen at West L.A. The department's cadre of officers best trained and equipped for crowd control, those assigned to Metropolitan Division, were either off duty or assigned elsewhere in the city.

Also keep in mind that, like the Hamas terrorists in Gaza they so admire, pro-Palestinian demonstrators in the U.S. welcome violent confrontations with the police, with the aim of generating provocative video clips that they can disseminate on social media and air on sympathetic media outlets. A case can be made for the police using restraint in dealing with such a mob, but only if the confrontation is exclusively between the mob and the police. However desirable it may be in some circumstances, restraint cannot come at the price of innocent blood. When innocent parties are being attacked, as occurred at the synagogue on Sunday, the time for restraint is over.

The ultimate decision on what police action to take in such a situation rests with the incident commander, who must weigh the law enforcement objectives against the resources available to achieve them. In this case, the objectives should have been clear enough, even to an inexperienced supervisor: protect lives and property and ensure the free exercise of rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

Yes, the pro-Palestinians have the right to protest in front of a synagogue but not to limit the safe access to it by those choosing to enter. Protesters blocking access to the synagogue should have been warned to move, and those failing to do so should have been arrested. It baffles me that, if the account from The Free Press writer Noah Pollack is accurate (and I have no reason to doubt it), the police didn't issue such an order and enforce it, using whatever lawful force was necessary.

Though I doubt the police at the synagogue on Sunday were under orders to stand down, is such an order unthinkable? Given how politicized the police profession has become, especially in cities, like Los Angeles, governed by leftists, the answer, sadly, is no. If L.A. Mayor Karen Bass, Brandon Johnson in Chicago, or Eric Adams in New York, to name just three prominent examples — if any of them were to detect an advantage in restraining the police from taking action against some group of favored political allies, would any of them be shy about communicating their preference to their police chiefs? And would those chiefs have the courage to uphold the law despite the mayor's wishes?

Sadly, it bears reminding that the war in Gaza continues and that there are still hostages, including Americans, being held there since being taken on October 7. Many of the perpetrators of the Oct. 7 atrocities remain at large and engaged in the war, including the architect of the attack, Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar. Pro-Palestinian protests will continue in this country until the Gaza war ends and very likely even longer.

Add to this already fraught climate the friction of the coming presidential election, and you have the ingredients for much tumult in the months to come. If politicians order their police officers to ignore lawbreaking, as was done for example in 2020 in Minneapolis, where the mayor ordered the police to abandon a police station to the incendiary whims of rioters, chaos inevitably follows.

A police officer has an obligation to disobey an order that is unlawful, immoral, or unethical, and any order that subjects innocent parties to peril would be all three. Who will stand tall when their moment to choose arrives?

Join the conversation as a VIP Member