VE DAY: The myth of the Bad War.

The elite cultural shift has been something to behold. In broadsheet op-eds and academic tomes, TV shows and movies, pundits and politicos are not simply critical of aspects of British history, pointing out the negatives amid the positives, the regress amid the progress. No, they are engaged in a one-sided, rotten-cherry-picking disavowal of the entirety of Britain’s past. They flatten out its history, reducing it to the singular evils of imperialism, racism and other species of bigotry.

And it seems as if Britain’s role in the Second World War has not been spared. Churchill himself is dismissed as a drunk racist, his statue the subject of activist animus, while the war effort has been reduced to an atrocity-laden exercise in empire preservation. The heroism of conscripts is erased, the ideals for which many fought are ignored. The elite myth of the Good War has arguably now been replaced by something just as false – the new elite myth of the Bad War.

All this has gone down well among a bourgeois left desperate to leave the grubby democratic politics of the nation behind for the gleaming transnational structures of the EU and assorted international climate-change treaties. But it has stuck in the throat of the majority of Brits who remain attached to their nation, for all its flaws, and soberly appreciative of its history. This is a division that has played itself out in several recent elections and, of course, in one famous referendum in 2016.

Having recognised just how unpopular this simplistic assault on Britain and its history is, Starmer’s Labour Party has tried to resist it. Starmer himself rarely seems to make a public appearance without a Union flag lurking, Triffid-like, in the background. Yet, as spiked editor Tom Slater has pointed out, Labour’s patriotic posturing rings hollow. Starmer’s attachment to the nation runs little deeper than flags and sporting allegiances. His is a skin-deep patriotism, one lacking in any political charge or historical consciousness.

This is hardly a surprise. Try as he might, he himself is cut from the same elite cloth as those decrying Britain’s past and attacking its nationhood. He is, after all, a politician who famously declared he prefers Davos to Westminster. A politician who consistently tried to overturn the vote for Brexit. A politician who would rather Britain was an EU member state ruled and regulated by Brussels than a nation state governing itself. No wonder his patriotism is so superficial, his national sympathy so shallow. It has to coexist with a deep-seated technocratic distrust of those who actually live and vote here.

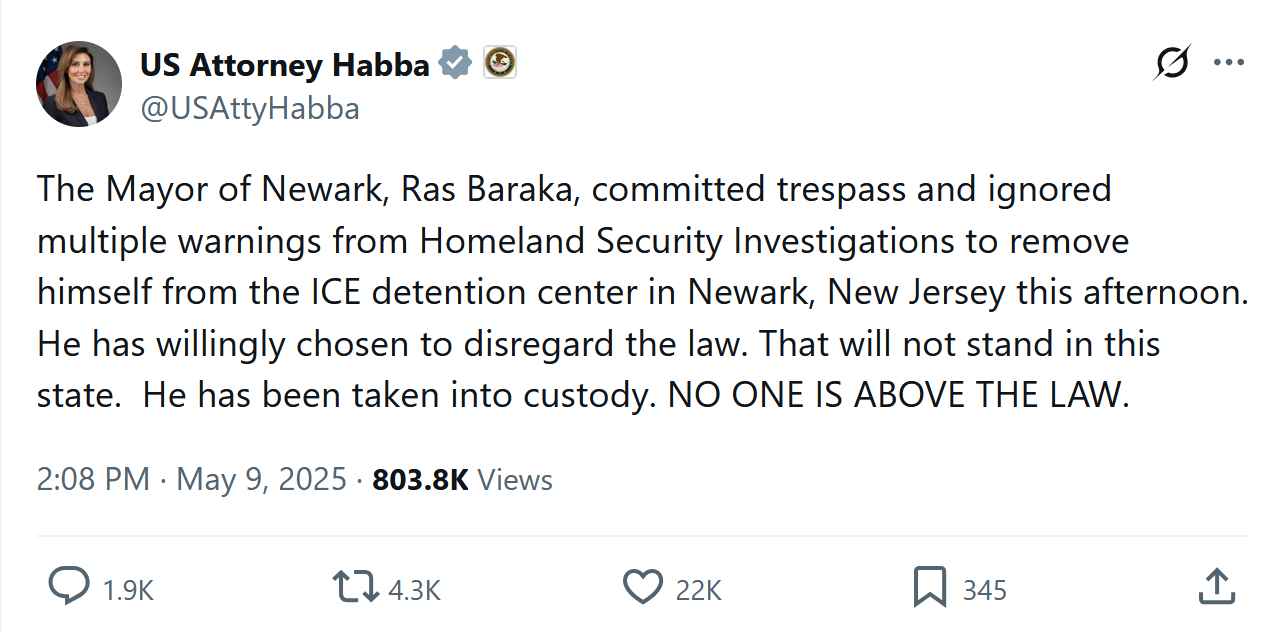

Meanwhile, back in the states, NPR goes full-on nihilist to “celebrate” VE Day: 80 years after VE Day a veteran says, ‘I hope people will see the futility of it all.’

[Harry Miller, age 96] went on to serve in the Korean War, and later he joined the Air Force, serving in the Vietnam War as well. He retired with the rank of senior master sergeant in 1966.

Today, Miller says he likes to share his story to help others understand the futility of war and hopefully inspire them to prevent similar conflicts from happening again.

“I hope, I hope people will see the futility of it all, because look at Germany. Look at Japan. Look at Vietnam. Look at Korea,” he said. “Everything is beautiful over there now, and it could’ve stayed that way, but no, we had to have a war.”

As Mark Steyn wrote in 1998 review of Saving Private Ryan:

Purporting to be a recreation of the US landings on Omaha Beach, Private Ryan is actually an elite commando raid by Hollywood and the Hamptons to seize the past. After the spectacular D-Day prologue, the film settles down, Tom Hanks and his men are dispatched to rescue Matt Damon (the elusive Private Ryan) and Spielberg finds himself in need of the odd line of dialogue. Endeavouring to justify their mission to his unit, Hanks’s sergeant muses that, in years to come when they look back on the war, they’ll figure that ‘maybe saving Private Ryan was the one decent thing we managed to pull out of this whole godawful mess’. Once upon a time, defeating Hitler and his Axis hordes bent on world domination would have been considered ‘one decent thing’. Even soppy liberals figured that keeping a few million more Jews from going to the gas chambers was ‘one decent thing’. When fashions in victim groups changed, ending the Nazi persecution of pink-triangled gays was still ‘one decent thing’. But, for Spielberg, the one decent thing is getting one GI joe back to his picturesque farmhouse in Iowa.

As Steyn concludes, “In that sense, Saving Private Ryan is the antithesis of Casablanca: the problems of one human being are what count; it’s all those vast impersonal war aims that don’t amount to a hill of beans.”