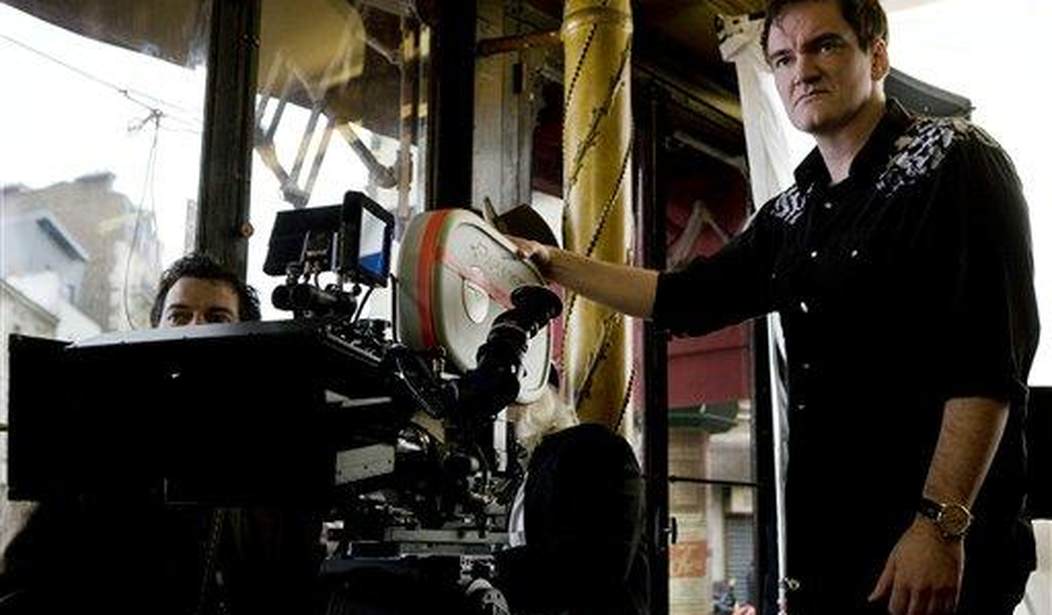

One of the legends of how Quentin Tarantino learned to direct was watching movies while working in a Southern California video rental store. However, the store contained not just fuzzy VHS cassettes of the usual Hollywood popcorn fare, but videos of obscure European art house films and other exotica the owner taped off the broadcasts of a Los Angeles cable channel whose fans simply called “The Z.”

DVDs and Blu-Rays, with their director’s cuts and bonus materials, would be unthinkable without the pioneering efforts of the Criterion Collection’s laser discs of the mid-to-late 1980s, a series of expensive titles aimed at film obsessives. But the Criterion Collection would be unthinkable without Z Channel.

The 2004 documentary Z Channel: A Magnificent Obsession, currently on Amazon Prime, was directed by Alexandra “Xan” Cassavetes, the daughter of John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands.

The cable channel began in 1974, with the initial goal of showing films in the pre-VCR era, and getting decent television reception for people living in areas like the Hollywood Hills, where terrestrial television antennas offered a notoriously snowy picture. (The local cable company’s early set-top box had alphabetical channel buttons for the then-novel concept of additional channels beyond the big three commercial networks and PBS.)

Near the beginning of the film, Chuck Ross, Z Channel’s first door-to-door salesman, walks through the Hollywood Hills and explains, “So, it was back in 1974, and I had just started selling cable television, and the Z Channel had just started. So, we came up here to the Hollywood Hills. And it was really great because these people had terrible reception. They couldn’t see anything on their television. And not only were we offering good reception, we gave them movies, uncut and no commercials, in their bedroom, in their living room, wherever they wanted it. They ate it up. It was very, very successful.”

Hollywood has been a company town since the 1910s. And in the 1970s and ‘80s, Z Channel’s programming flattered Hollywood’s insiders and influenced Academy Awards contests. Even before Ross appears onscreen, directors such as the aforementioned Tarantino, Robert Altman, Henry Jaglom, Alan Rudolph, Penelope Spheeris, James B. Harris (whose career began as Stanley Kubrick’s first producer), actor James Woods, and actress Theresa Russell namecheck the eclectic films they first saw on The Z.

Also, before Ross appears onscreen, there’s a flashback to a 1989 L.A. news radio report of Jerry Harvey, the channel’s head of programming, shooting his wife and then turning the gun on himself.

Interlinking those two segments is a short clip from the 1962 western Ride the High Country, in which Mariette Hartley asks Joel McCrea, “My father says there’s only right and wrong — good and evil. Nothing in between. It isn’t that simple, is it?” McCrea replies, “No, it isn’t. It should be, but it isn’t.”

Cassavetes’ documentary intersperses breezy then-recent interviews with Hollywood legends, somewhat more harrowing conversations with former Z Channel employees, clips from the all-embracing fare shown on The Z, and in its creepiest scenes, 1980s radio interviews of Harvey speaking in an unsettling near monotone, played on top of grainy, slightly desaturated and noticeably unpopulated shots of Hollywood and L.A.

With his encyclopedic knowledge of film, Harvey began his career in the since-demolished Beverly Canon Theatre, where in 1974, he showed the uncut version of Sam Peckinpah’s classic 1969 anti-western, The Wild Bunch. Peckinpah himself arrived to deliver the print, and the two quickly became friends. Harvey co-wrote the script for a spaghetti western directed by Monte Hellman called China 9, Liberty 37, starring Warren Oates, Jenny Agutter, and Peckinpah in a rare acting role, which was released in 1978.

After Harvey kept watching cable TV and yelling at the screen at how bad the programming was, his then-girlfriend suggested he write a letter to the cable company, whose management was impressed with his knowledge of film, and hired him. Shortly after being hired, Z’s then-head of programming quit, Harvey replaced him, and he, and the channel, were off to the races.

How Annie Hall Won Its Best Picture Oscar

But even before Harvey arrived, Z Channel was a smash with Hollywood elites. In 1978, the New York Times reported:

The Academy Award‐winning “Annie Hall” had one distinct advantage over its four competitors. To see it, the majority of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences voters had only to reach over and turn on their television sets.

The week before nominating ballots were mailed last January, “Annie Hall” played on the Z Channel in Los Angeles, part of an $18.95‐a‐month cable television system. Since 1975, studios have been cautiously placing a few of their new movies on Z for one special screening that usually coincides with the mailing of the academy ballots. The correlation to unexpected acting nominations has been surprisingly high. Diahann Carroll for “Claudine,” Glenda Jackson for “Hedda,” Maximilian Schell for “The Man in the Glass Booth,” Liv Ullmann for “Face to Face” and Marcello Mastroianni for “A Special Day” probably owe their nominations in large part to the special rooms to see”…Marcello Mastroianni probably owed his Oscar nomination in large part to a showing on Z. screenings, while Art Carney may owe his Oscar for “Harry and Tonto” to a showing on Z just after the final ballots were mailed out.

“We have 87,000 subscribers,” Frank Hickey, head of marketing for Theta Cable, said. “Almost 47,000 of them take the Z channel, including all subscribers who live in Beverly Hills and Bel Air. Two years ago, a survey that we did not Commission said that 75 percent to 80 percent of academy members were subscribers.

A few years later, during an era when VCRs were just beginning to arrive in homes, and pre-recorded videotapes were rare and quite expensive, Z Channel offered Hollywood elites (and everyone else in the city who signed up) a remarkably diverse playlist, with then-recent blockbusters like The Empire Strikes Back playing alongside little-seen foreign art films such as 1959’s Black Orpheus. The Z often showed films shot for widescreens in theaters in a letterboxed format to preserve their aspect ratios, another practice the Criterion Collection would adopt two decades before widescreen HDTVs arrived in America.

While channels such as HBO and Showtime were becoming major powerhouses in other cities, in 1982, they had 14,000 and 7,000 subscribers in Los Angeles, respectively. Z Channel had 80,000. The late film critic F.X. Feeney, who wrote for Z Channel’s monthly newsletter, and co-produced the documentary, tells his interviewer about attending a cable company convention in the 1980s at a large hotel, with representatives of channels including HBO, Showtime, and The Movie Channel. “Big table, dais, pitchers of water, nameplates,” Feeney tells his interviewer. “Jerry’s down at the other end. And everybody’s going down the list, talking about how many committees they’ve got, how many market research [firms]. ‘We hired this firm from New York.’ ‘We’ve got this firm from Chicago.’ ‘Jerry, how many firms do you draw on to choose your programs?’ He says, ‘I don’t consult anybody. I just see movies. I just show good movies.’ ‘Yeah, but [what’s] your decision-making process? Who’s your committee?’ ‘I don’t have a committee. We have people in the office; we talk, we like movies, but basically, it’s just whatever we want to see.”

The Birth of the Director’s Cut

Z Channel could give remarkable critical reassessments of films that had failed at the box office. Harvey was friends with director Michael Cimino, and Cimino’s 1980 film Heaven’s Gate, his follow-up to The Deer Hunter, was such a flop, it put venerable studio United Artists out of business. Because it played dreadfully in sneak previews and received deadly reviews by critics, UA cut over an hour from the film.

In 1982, Harvey insisted that UA management reassemble the uncut version, aired it, and it became a ratings smash, due to the film’s infamy. Feeney says, “I have this fantasy that in the year 2050 or the year 2075, they’re gonna read about the furor that attacked Heaven’s Gate; the furor that came down upon Heaven’s Gate, and they’re not gonna believe it. It’s gonna seem like science fiction.” Feeney also notes that this 1982 airing was the first time a film was marketed as “the director’s cut.”

Similarly, James Woods tells of appearing in Salvador, Oliver Stone’s first directorial effort, co-starring James Belushi. Despite receiving several good reviews from critics, it too made a hasty retreat from theaters. However, due to Harvey championing the film and airing it frequently on Z Channel in the fall of 1986, Woods and Stone each received Academy Award nominations, which would have never happened otherwise.

Harvey championed the 1975 film Overlord, a low-budget WWII movie whose scope was significantly expanded by seamlessly interspersing documentary footage of D-Day and the training leading up to it with newly shot black and white dramatic footage of actors in scenes written to work the 1940s shots. Harvey flew Stuart Cooper, the film’s director, into Los Angeles and set up interviews with critics.

Similarly, Harvey aired Penelope Spheeris’ 1981 documentary of the L.A. punk rock scene, The Decline of Western Civilization. Spheeris tells of the film’s theatrical debut, “We showed the film one night, midnight. They had to shut down Hollywood Boulevard, and 300 motorcycle cops came. We had a letter afterwards from Daryl Gates, the chief of police, saying, ‘Please don’t ever show that movie in Los Angeles again.’”

“You Never Know When You’re Living in a Golden Age”

A Z Channel subscription came with a monthly magazine that both served as a programming guide and critiqued the channel’s films with lengthy Roger Ebert-style reviews. Feeney, who wrote for Z’s monthly guide, tells his interviewer, “My belief, and I know that this is Jerry’s belief, too, is that if you appeal to the most intelligent member of the audience, everybody else follows along. There’s this feeling that you have to appeal to the common denominator. Jerry and I hit on the phrase, ‘the uncommon denominator.’ That’s what we want, because we want to go for the smart folks — because everybody is smart.”

Today we take cable channels like Turner Classic Movies and Cinemax (which borrowed The Z’s late-night softcore porn approach) for granted, along with Blu-Rays packed with bonus material. But somebody had to do it first, and for a time, Z Channel did it right. As writer-director Alexander Payne says – while wearing a Z Channel t-shirt – “You just never know when you’re living in a golden age.” But it was not to last.

As shown by his remarkably eclectic programming choices, Harvey was brilliantly functional in the office, endlessly calling studio executives insisting they track down the obscure film he had to have yesterday, but self-medicating, alternating booze and No-Doze pills. He visited a psychiatrist at least twice a week. He told employees that he was crazy, and his girlfriend that one day he was going to lose his struggle with reality. And sadly, ultimately, he did. Harvey’s “Magnificent Obsession” drove him to great heights as Z Channel’s programming impresario. But it ultimately doomed him, and worse, his wife.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member