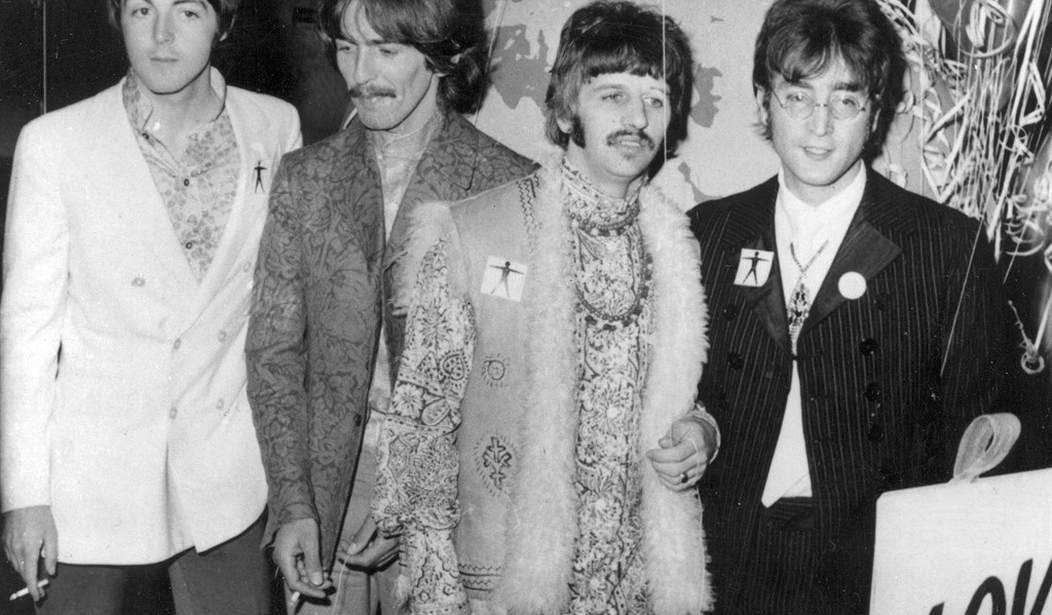

What more is there to say about the Beatles’ Get Back mini-series on the Disney Plus streaming platform? I wrote up my initial take on Thanksgiving Day. But having now survived all eight hours or so, here are a few more thoughts, beginning with the series’ demonstration of the Beatles’ charisma. The footage has a definite meta quality to it; you wonder how much the Beatles are playing for the cameras, particularly once the band leaves drafty Twickenham Film Studio for their own studio in the basement of the Apple building on Savile Row. Lennon clearly enjoyed demonstrating his rapier-like wit, and McCartney seemed to think he was coming across as a major musical deity. Ringo, about to shoot The Magic Christian with Peter Sellers, also enjoyed being in front of the camera. Only Harrison was initially uncomfortable, leading to his temporarily quitting the band.

As the best moments of the mini-series demonstrate, the Beatles as a foursome had charisma to burn. According to George Martin it was that charisma that led him to sign the band to EMI even more so than their nascent musical skills:

“I did think they had enormous talent,” George [Martin] would later allow, “but it wasn’t their music, it was their charisma, the fact that when I was with them they gave me a sense of well-being, of being happy. The music was almost incidental. I thought, ‘If they have this effect on me, they are going to have that effect on their audiences.’” In short, he was absolutely charmed by them, by their personalities far more than their music at this stage. As [Martin] later remarked, “You actually felt diminished when they left.” For the Beatles’ part, the Scousers from Liverpool were understandably intimidated by the thirty-six-year-old [Martin] and said, ‘Yeah, I don’t like your tie.’”

After the formality of [Martin’s] lengthy diatribe, the room lapsed into an awkward silence. This was Abbey Road, after all, the studio where technical personnel wore crisp white lab coats, while administrative types like [Martin] donned coats and ties. At first, [Martin] didn’t register the joke. He would later remember being especially pleased with the tie that he had chosen that day— a black number featuring a red horse motif. George Harrison briefly felt as if he might have crossed a line with his deadpan attempt at humor, later recalling, “There was a moment of ohhhhh, but then we laughed and he did too. Being born in Liverpool you have to be a comedian.” Once everyone had joined in the merriment, the floodgates of the Beatles’ penchant for humor and self-deprecation opened wide up. As [early Beatles engineer Norman] Smith remembered, Harrison’s moment of levity “cracked the ice, and for the next 15 to 20 minutes the Beatles were pure entertainment. When they left, George and I just sat there saying, ‘Phew! What do you think of that lot then?’ I had tears running down my face.”

Later in their careers, the Beatles could turn on the charm whenever the camera and/or the tape recorder was rolling. Geoff Emerick, who engineered arguably their best albums, including Revolver, Sgt. Pepper, and Abbey Road, quit the group over what he perceived as the tense atmosphere of the “White Album’s” sessions, except for when media figures dropped by:

Kenny Everett, the BBC disk jockey, came into the studio and did an interview with the four Beatles while they were working on “Don’t Pass Me By.” It was a distraction, but John got into quite a jolly mood, hamming it up for the microphone, so it did help lighten the atmosphere. The Beatles always could switch the charm on and off, and for that half hour, they became their Hard Day’s Night characters, clowning around and acting like the lovable moptops that the public knew. It was nice to see, and I began thinking that maybe there was a glimmer of hope after all. But it didn’t last for long. As soon as Kenny left, they reverted back to their miserable selves.

Power Shift

There were multiple power plays going during the “White Album” sessions. While John Lennon had formed the Beatles and dominated its early recordings, he became increasingly dissipated during the period of 1966 and ’67 due to his many LSD trips. As a result, by Sgt. Pepper, Paul McCartney was increasingly running the show. McCartney’s power only increased when manager Brian Epstein died in 1967. As Emerick wrote in his autobiography:

Looking back on it all these years later, it’s obvious that Paul saw a vacancy in leadership after Brian died, and he stepped in. Perhaps that ultimately led to the band’s breakup, but the fact of the matter is that someone had to. Surely Ringo and George Harrison couldn’t, and between his drug use and unfocused mind, John simply wasn’t capable of it at that point in his life. As I see it, Paul saved the band. After Brian’s passing, they could have decided to quit while they were ahead, but he kept them going for another few years. As it turned out, they would be rocky, divisive years, but no one knew that at the time, and the Beatles still had some great music left in them. So just as Paul had assumed some of the production responsibilities from George Martin, he now filled Brian’s shoes as well. Sure, he made mistakes, but he kept the greatest band in the world going at a time when they could have easily crumbled. I reckon he deserves a lot of credit for that.

There’s a touching scene in Part II of Get Back when McCartney tells Lennon, “You have always been boss. Now, I’ve been, sort of, secondary boss,” attempting to reassure John that he’s still in charge of the group, despite seeming to be more interested in bed-ins, “bag-isms” and posing naked on album covers with Yoko Ono.

Having fallen madly in love with Ono the previous year, her constant presence alongside Lennon was John’s way of tacitly saying to McCartney, “if you want to keep this band together, you need me, and I want Yoko. Take it or leave it.”

Because Lennon and McCartney dominated the band’s songwriting and recording process, the two viewed Harrison and Starr as somewhat lesser Beatles. As the Get Back footage demonstrates, Ringo was vital as a human drum machine, playing endlessly during the band’s increasingly lengthy sessions, and inventing brilliant drum patterns. But George was another story, hence his temporary divorce. Emerick wrote that “In general, sessions where we did George Harrison songs were approached differently. Everybody would relax—there was a definite sense that it really didn’t matter. It was never said in so many words, but there was a feeling that his songs simply didn’t have the integrity of John’s or Paul’s—certainly they were never considered as singles—and so no one was prepared to expend very much time or effort on them.”

Harrison’s solution during the “White Album” when he didn’t think John and Paul were taking “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” seriously was to bring in his friend Eric Clapton to play the solo. Suddenly, having to deal with one of the most famous electric guitar players in the world, Lennon and McCartney suddenly smartened up and rose to the challenge.

Harrison would employ a similar strategy during the Let It Be sessions: bring in his friend Billy Preston to play keyboards.

When Preston shows up about an hour and twenty minutes into Part II of the Get Back miniseries, the band suddenly starts to gel, and instantly songs begin to sound like the Let It Be record. Both are in large part due to Preston’s keyboard chops and his instant chemistry with the band.

It may also help that George Martin, the Beatles’ longtime producer, is much more of a presence in Part II, working with producer-engineer Glyn Johns to move the proceedings further.

The Cheapskate Epitaph, Reborn

It’s understandable that Let It Be, both the album and film, were seen for decades by many as the Beatles’ swan song, even by those who knew that Abbey Road, while it was released nine months after the Let It Be’s sessions, preceded the release of Let It Be. It’s also understandable how, compared to Abbey Road, Let It Be is seen as the inferior album, particularly given its longtime reputation as “the Beatles’ last album:”

The album was met with mixed reviews at the time of its release. [New Music Express] critic Alan Smith wrote “If the new Beatles soundtrack is to be their last then it will stand as a cheapskate epitaph, a cardboard tombstone, a sad and tatty end to a musical fusion which wiped clean and drew again the face of pop”. Rolling Stone magazine was also critical of the album, citing Spector’s production embellishments as a sore point: “Musically, boys, you passed the audition. In terms of having the judgment to avoid either over-producing yourselves or casting the fate of your get-back statement to the most notorious of all over-producers, you didn’t…”

It didn’t help that shortly after those reviews were published, John Lennon had his epic 1970 interview with Jann Wenner of the Rolling Stone, and went out of his way to trash the film and its recording sessions, and describing Phil Spector’s production as a remarkable salvage effort:

“[Spector had] always wanted to work with the Beatles,” John Lennon told Jann Wenner in a 1970 Rolling Stone interview, “and he was given the sh*ttiest load of badly recorded sh*t with a lousy feeling to it ever, and he made something out of it. He did a great job.”

Few others involved in the project agreed. In his 2015 autobiography, Sound Man, Glyn Johns did not mince words, writing, “after the group broke up, John gave the tapes to Phil Spector, who puked all over them, turning the album into the most syrupy load of bullsh*t I have ever heard.”

When George Martin discovered that EMI wouldn’t allow him his usual producer credit on Let It Be, despite his role with the Beatles during the project, his response to the record company brass was that the album’s rear sleeve should read, “Produced by George Martin, Overproduced by Phil Spector.”

But today, the album version of Let It Be is seen in a much kinder light. As the Daily Beast went out on a limb to note last year, “Let It Be, the Beatles’ ‘Worst’ Album, is Actually Pretty Damned Great.”

And it was arguably made even better by the 2003 release of the unfortunately titled Let It Be…Naked, which stripped away many of Phil Spector’s overdubs, and used the bare-bones version of “The Long and Winding Road” seen in the Let It Be movie, one of several numbers the Beatles didn’t record on the rooftop, in part because they couldn’t lug a grand piano up to the roof. It’s unfortunate that Get Back doesn’t use the complete versions of the acoustic songs the Beatles recorded the day after the rooftop concert, but this is likely due to Peter Jackson wanting to keep Let It Be as its own movie.

As to the surprise that Jackson’s miniseries cast the Beatles in a more cheerful light than Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 1970 documentary, this is the power of editing down from a massive amount of footage and choosing the bits you want to see. In Alan Alda’s otherwise forgettable 1986 film Sweet Liberty, the former M*A*S*H star, now playing a history professor hired by a film production about the Revolutionary War, and is shocked by how much of his technical advice is ignored in favor of a Hollywood-izing 1776. For the climactic battle, he convinces the actors to do it right, much to the chagrin of the director, played by the late Bob Hoskins. Afterward though, the film’s cinematographer, played by veteran character actor Saul Rubinek is pretty chipper about the whole thing, telling Alda, “I shot it with six cameras. I can put it together any way I want. It’ll be terrific — you’re gonna love it!”

Similarly, Jackson “was granted access to 57 hours of video footage from the 22-day Let It Be album sessions and more than 100 hours of audio, and asked to try and make a documentary with it.”

As the New York Times noted in mid-November during the runup to Get Back’s release, “Of course, the Beatles did not disband in January 1969. They went on to record ‘Abbey Road’ later that year:”

But Jackson’s mini-series makes clear that the end was nigh. If there is a true culprit in the breakup, it was the business conflicts that ensued during 1969, when the group tussled over its management, and Lennon and McCartney tried but failed to take control of the company that held their songwriting rights.

Those problems are foreshadowed in “Get Back” with the utterance of a single name: Allen Klein, the American business manager who arrives a few days before the rooftop show to pitch his services for the band. Shortly after the events shown in “Get Back,” Lennon, Harrison and Starr all signed on with Klein; McCartney declined, and the schism was never repaired. Klein died in 2009.

When Klein’s name was uttered, I found myself yelling at the screen, “Don’t do it boys — you’ll be sorry!”

The Ballad of John and Yoko

“Our movie doesn’t show the breaking up of the Beatles,” the Times quoted Jackson as saying, “but it shows the one singular moment in history that you could possibly say was the beginning of the end.”

There is a bit of revisionist history in some of the interviews Jackson gave regarding Yoko Ono’s role in the Beatles’ dissolution, such as this Grauniad article from Saturday, November 20th:

Another moment that gave him particular delight involves McCartney discussing Lennon and the presence of his soon-to-be wife Yoko Ono in the studio (at one point we watch Lennon and Ono celebrate, mid-song, as they get the news that Ono’s divorce has been finalised). McCartney, as if gazing into a crystal ball, says: “It’s going to be such an incredible sort of comical thing, like, in 50 years’ time, you know: ‘They broke up because Yoko sat on an amp.’”

“I was stunned when I first heard that,” says Jackson. “Of course, they didn’t break up because of Yoko, but Paul can do an interview today and say it wasn’t and people will take it with a grain of salt. You can’t do better than [having] a contemporary source.”

Yoko sitting on an amp didn’t break up the Beatles — the Beatles were used to having non-members in the studio when they were recording, and created at least two “happenings” to bring outsiders in, such as the recording of the song “Yellow Submarine,” where the band created a party atmosphere to capture sound effects — such as the roaring laugh at 56 seconds into the song from George’s then-wife, Patti Harrison. The Feb. 10, 1967 orchestral session for a “Day in the Life” was attended by members of the Rolling Stones, and even the Monkees:

However, Yoko’s worldview and artistic temperament certainly did play a major role in the band’s disintegration, as Ian MacDonald wrote in Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties in the chapter on post-Get Back, pre-Abbey Road single, “The Ballad of John and Yoko:”

The softness cultivated in him by Yoko Ono had always been there, seeking expression; indeed, it was awoken before he met her by LSD. With its beatific impersonality, acid had a profound impact on the outlook of a generation, and Lennon, who took it in enormous quantities, was one of its most influential converts. Among other things, what the drug did for him was to elevate his psychologically conditioned sympathy for the underdog into a universal concern for love and peace which, striking him with the force of conversion, quickly inflated into messianism…

Equally contradictory, Yoko Ono balanced a hard-headed, even heartless percipience with a fey narcissism which, held in check by her intellectual peers in the New York avant-garde scene, ran riot once liberated by Lennon’s intuitive and untutored indiscipline. While exchanging comfort and confirmation, the pair brought out the worst in each other, he inadvertently diverting her from the sharp Oriental Dadaism of her early work into a fatuous fugue of legs, bottoms, and bags, she encouraging him to believe that orderly meaning was a male hang-up and that the secret of peace was to be sought in pure sensation and guiltless sex. Since she was his intellectual superior, most of the influence ran from her to him; and, since he was her artistic superior, this influence streamed straight into the public domain through his music. Their activities accordingly became unguardedly naive, their gesture of letting their pants down on the cover of Two Virgins showing how far intelligent people can infantilise themselves by pretending to believe what at heart they don’t. Under the ostensibly selfless holy foolery they indulged in during 1968-70 was a core of exhibitionistic self-promotion. Behaving as if they had personally invented peace, they jetted round the world in first-class seats selling it at third-rate media-events. This was arrogant as well as silly, and the news media’s derision, of which “The Ballad of John and Yoko” self-righteously complains, was not only inevitable but, in the main, justified.

Of all the dangerous ideas Ono unloaded on her spouse around this time, the most damaging was her belief that all art is about the artist and no one else. Serving to confirm Lennon’s self-absorption, this also torpedoed his universalism, and it was as a man struggling to resolve this exacerbation of his lifelong emotional contradictions that he reeled from heroin to Primal Therapy to Maoism and finally to drink during the next three years. Otherwise scathingly honest, he unwittingly put himself into a position in which he was obliged to defend things that, deep down, he cared nothing about. Uncompromising as ever, he threw himself into this trap with total commitment, not only refusing to draw a line between his public and private life but going out of his way to personalise everything that happened in his vicinity, a self-centredness which could hardly avoid occasionally degenerating into paranoia, as “The Ballad of John and Yoko” demonstrates. Indeed, so outrageously egocentric is this song that it’s difficult to know whether to deplore its vanity or admire its chutzpah in so candidly promoting Self to artistic central place.

In his Friday Nov. 19 article in the Washington Examiner titled, “Get Back, Yoko,” Eric Felten wrote:

The crowd I first saw the original film with weren’t interested in a happier spin on the Beatles. They were there to render judgment, to be the choric voice of the Beatles’ community declaring their disapproval. In other words, they were there to boo. They were there to boo Yoko Ono. If I remember the film correctly, the opening credits were barely done when we see John Lennon, and there is Yoko, sitting right beside him.

“Boooo.”

Then, there is Yoko, knitting right beside him.

“Boooo.”

For the length of the movie, every time Yoko was on camera, the crowd booed, as if to say, “Take that, Yoko, for breaking up the Beatles.”

* * * * * * * *

Either way, the Jackson remake of Let It Be is a reminder that documentarians are not in the unambiguous truth business. Take the same pile of reels, and one can tell diametrically opposed stories. It’s a phenomenon worth remembering when watching someone get skewered on 60 Minutes.

That said, one thing is constant: I still expect to hear Yoko booed.

While Allen Klein deserves the lion’s share for causing the break-up of the Beatles, believing that Yoko’s continual presence played little or no impact is a bit of historical revisionism way too far. But then, she had to sign off on the project in the first place.

Ultimately, Get Back is a frustrating mini-series. As The Onion joked after its release, “New Beatles Doc Gives Man Greater Appreciation For How Long 8 Hours Feels.” However, it does demonstrate the Beatles’ creative process at work. Or at least one of their creative processes. Rather than the endless overdubs of the Revolver/Sgt. Pepper sessions, the Beatles tried to make a live album in the studio (and on the rooftop) — and in the end, succeeded. If Klein hadn’t entered the picture, or if Lennon and McCartney had given George Harrison more creative space, it’s entirely possible they could have continued into the ‘70s, perhaps adopting the policy of the Rolling Stones or Genesis, who gave their band members plenty of room for solo projects in the 1980s. Since it wasn’t to be, Jackson’s Get Back is the visual swan song the Beatles deserved.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member