At age 76, Jimmy Page has reached that autumnal phase of life where a tell-all autobiography is expected of a superstar rock musician. In 2010, Keith Richards released Life, his surprisingly readable autobiography, in which he explored in detail his former heroin addiction, claims about having his blood changed in 1973, and snorting the cremated remains of his father, among numerous other lurid details. (My favorite recurring leitmotif in Richards’ book are the numerous times he tells a fellow musician that he’s taking too many drugs. One would think that being told you’re overindulging pharmaceuticals by Keith Richards would check even the most hardened addict instantly into rehab, but that rarely was the case, given the high body count of those in the Stones’ orbit.) Two years later, Pete Townshend released Who I Am, his look back at his child abuse via his grandmother, his discovery of the Indian guru Meher Baba, and his infamous run-in with the law in 2003. Last month, Peter Frampton released his own autobiography, Do You Feel Like I Do?

However, unlike Richards and Townshend, Jimmy Page has never been the most forthcoming interview. As long as the conversation stays on the topic of old Les Paul electric guitars and how he (or more likely his then-engineer Andy Johns) created John Bonham’s monumental drum sound on “When the Levee Breaks,” he’s fine. But there’s a reason why Page’s 2014 GQ interview with music critic Chuck Klosterman was titled “Jimmy Page and the Grouses of the Holy.” When Klosterman attempted to ask Page about his alleged (very alleged) heroin addiction in the late ‘70s through the early ‘80s and how he recovered from it, a testy Page responded angrily, “How do you know I had a heroin problem? You don’t know what I had or what I didn’t have. All I will say is this: My responsibilities to the music did not change. I didn’t drop out or quit working. I was there, just as much as anyone else was.”

Much of Klosterman’s interview with Page continues in that vein, leading Klosterman to conclude:

That aforementioned Mud Shark Incident? You will find that tale in the unauthorized biography Hammer of the Gods, written by a man who spent only two weeks with the group and who heard the story from a fired road manager the band has essentially disowned for two decades. Now, this is not to say the event didn’t happen, just as it’s virtually undeniable that Page was intensely involved with drugs. But these are not things he talks about. These are simply things he chooses not to deny. And that makes the extraction of reality profoundly complex.

The Coffee Table Books of the Gods

In the 1970s, stung by early scathing reviews in publications like Rolling Stone, Led Zeppelin and their manager Peter Grant kept the rock press on a very tight leash. As a result, their excesses were largely unknown until the 1985 bio Hammer of the Gods, by rock critic Stephen Davis, opened a floodgate of lurid details from rock biographers who interviewed those in the band’s inner circle, who seemed to confirm many of Hammer of the Gods’ details.

Jimmy Page, being so unforthcoming with the press, with massive potential baggage trailing from the ‘70s — rumors of mud sharks, rumors of underage groupies, rumors of drug and alcohol abuse, rumors of a massive amount of coke-fueled ultra-violence committed by the band’s manager Peter Grant, all culminating in the 1980 death by alcohol-induced asphyxiation of drummer John Bonham’s in Page’s Windsor mansion, and the disbanding of the group — is not someone who is going to cash in, in his mid-70s, with a tell-all autobiography. However, he’s found a way around this problem: rather than write the proverbial warts-and-all autobiography, release slick massive coffee-table books stuffed to the gills with color photographs and weave the story you want to tell around them.

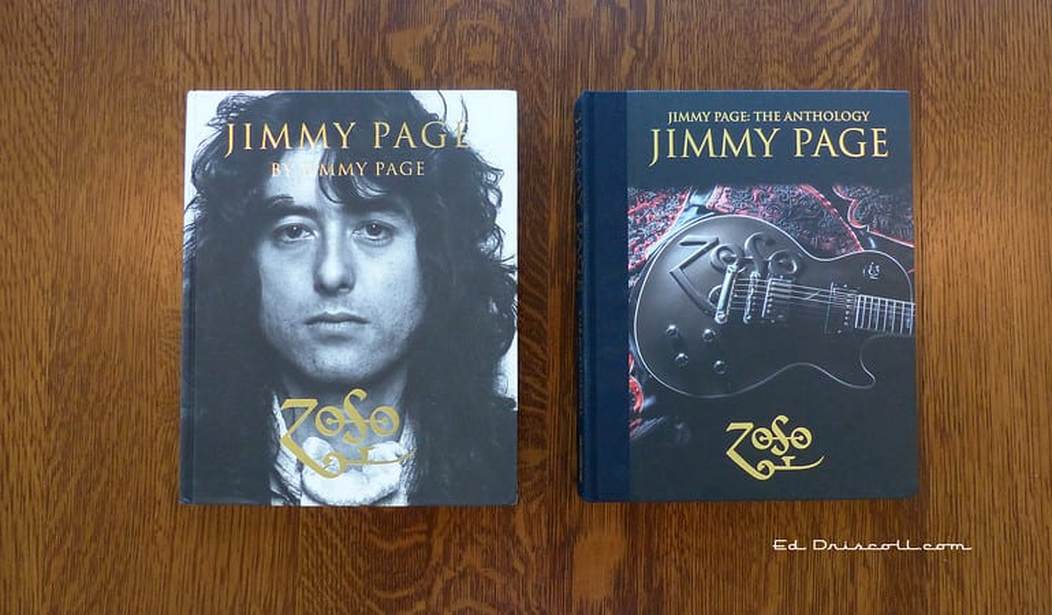

Page’s first book, with 500 pages and over 650 photos and illustrations, was simply titled Jimmy Page by Jimmy Page, originally published by Britain’s Genesis Publications in 2010 in a run of 2,500 copies, each signed by Page, with each copy selling for $700. (In 2012, one copy sold at auction for $1750. Such is the value of a book autographed by the founder of the 1970s’ biggest rock group.) Page’s first book was reissued in 2014 in a non-autographed mass edition that sold at the much more reasonable price of $60.00. (It currently sells on Amazon for $40.99.)

His latest book, Jimmy Page: The Anthology, originally published last year by Genesis Publications, repeated the formula. The first run was of 2,500 copies, each signed by Page, with each selling for $480. A mass edition that began shipping in October of 2020 is currently selling on Amazon for $36.00. It contains 400 pages, many of which are filled with newly photographed examples of Page’s guitars, his amplifiers and studio equipment, and his stage clothes.

Jimmy Page: The Anthology builds on Page’s involvement in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition of rock artifacts titled Play It Loud: The Instruments of Rock & Roll, which ran from April 8 to October 1 of last year. (I was lucky enough to walk through it last April, when no one knew that coronavirus, travel bans and quarantines, and urban riots would dominate the headlines of the following year.)

If you or a friend or family member is a serious collector of “guitar porn” — beautifully lit and photographed examples of rare, vintage guitars, then Jimmy Page: The Anthology will be a most welcome book indeed. It is filled to the brim with dramatically lit and posed photographs of Page’s many guitars over the years. The photos start with the lowly 1959 Grazioso Futurama, a silly-looking Czechoslovakian-made Fender Stratocaster knockoff, since American imports were still restricted in England. It ends with a photo of all of Page’s iconic Led Zeppelin-era guitars lined up on a multi-guitar stand atop a touring flight case: The inexpensive Harmony Sovereign that he wrote “Stairway to Heaven” on; the three-pickup Black Les Paul Custom that he played at the Royal Albert Hall in 1970, and used for much of his mid-1960s British recording session work; the lowly 1961 Danelectro, essentially a student guitar with a Masonite body, that Page made iconic with his in-concert use of the guitar on “Kashmir” and “White Summer”; Fender’s recent reissue of his 1959 Telecaster reproducing his hand-painted dragon design that he played during Led Zeppelin’s earliest barnstorming days of touring; the 1959/60 sunburst Gibson Les Paul Standard that Page is most associated with, as it was his primary stage guitar with Led Zeppelin; the 1971 Gibson EDS-1275 double-necked 6/12 string guitar that Page had special-ordered from the guitar manufacturer to play “Stairway to Heaven” live, and other iconic songs such as “The Song Remains the Same” and “The Rain Song”; and in the foreground, the gold-top Les Paul with a high-tech Transperformance computerized tuning system, which he used in the 1990s, most prominently on his 1994 MTV reunion concert with Robert Plant on “Kashmir,” the program’s climactic song, in which, via the press of a button on the guitar, he went from the song’s primary guitar tuning, DADGAD, to standard tuning at the end of the song for some more conventional power chord riffing to conclude the song in typically explosive Zeppelin-style fashion.

Along the way, there are close-up photos of all those instruments, and some of the more obscure instruments Page has played over the decades, and his amplifiers, both the small Supro amp he recorded the first Led Zeppelin album with, which, when carefully adjusted and miked, generated a massive-sounding recorded tone, and the huge back-line of Marshall amps Page used to reproduce that tone when playing live in concert halls.

There are also examples of Page’s most iconic stage clothes, including the evolution of his iconic mid-1970s “dragon suit.” Budding rockstars will no doubt be studying the photos of Page’s wardrobe in an effort to assemble their own looks.

In the Days of My Youth

Page’s earlier coffee table book, titled simply Jimmy Page, is essentially a scrapbook of photos dating back to Page’s earliest days in skiffle and rock and roll bands. (Both books begin with a now hilariously ironic photo of a very young Page as a choirboy in St. Barnabas Church in Epsom, taken by the choirmaster with the equally incongruous name of Mr. Coffin.) These are followed by photos of Page as a session man, performing with early crush Jackie DeShannon, and then his stint in the last days of the Yardbirds.

After Jeff Beck left, and the Yardbirds continued as a four-piece, Page used the group as a test-run for many of the ideas that he would later incorporate into Led Zeppelin. “Dazed and Confused,” with its violin bowed solo section, “Tangerine,” “White Summer,” and the riff to “The Song Remains the Same,” all began in the Yardbirds.

This book features numerous photos from Led Zeppelin’s earliest days, or as they were originally billed, “The New Yardbirds,” playing in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, in a series of concerts that the actual Yardbirds had scheduled, before their implosion. With replacement musicians who left the Yardbirds’ stiff rhythm section and Keith Relf’s spirited but limited vocals in the dust, Led Zeppelin quickly exploded in popularity.

By 1971, Page hit upon a new way to record the band, renting a former Victorian work home called Headley Grange, where they could eat, drink (and boy did they drink), and sleep their music. Also rented was the Rolling Stones’ Mobile Studio. The results were the backbone of their career-defining untitled album, popularly referred to as Led Zeppelin IV, and containing a track that receives massive airplay even today called “Stairway to Heaven.”

As a result of the album’s massive success, Zeppelin’s tours of the United States were based around a rented Boeing 720 called the “Starship,” with the band’s name painted on the plane’s fuselage. For the next four years, as the photos selected by Page highlight, Zeppelin would be at their apogee. After five concerts in London’s Earl’s Court at the end of their 1975 American tour, Page and Plant split up, with Plant engaging in travel while on the Greek island of Rhodes. There, Plant would have a horrific accident in his rented Austin Mini, resulting in a shattered right leg and elbow.

Fearful that Zeppelin would be grounded forever, Page reconvened the group and booked just 18 days in Munich’s state-of-the-art Musicland Studio to record what would be their 1976 album, Presence. According to road manager Richard Cole, it was during these grueling sessions that Page became hooked on heroin. (And possibly other drugs; photos in Page’s book show him rehearsing for Zeppelin’s 1977 tour show him wearing a Rorer 714 t-shirt, the manufacturer and its brand number for Quaaludes.) Page’s nasty habits did not help his live playing; bootlegs of the band in 1977 are readily found on YouTube, and while the group had their occasional good nights, Page’s lead playing in particular was often a shadow of its former self. The stage suit Page had tailored for the 1977 tour reflected his newfound habits in three ways: a white suit, festooned with dragons and poppies.

Naturally, this being a book assembled by Jimmy Page, you won’t find him making that connection in print, and it’s this phase of his life that has made him so tight-lipped and cross in interviews.

Three years after the 1977 tour, it was all over, after John Bonham’s death. As with the individual Beatles after their breakup, Page never scaled heights as great as he did with Zeppelin. However, there was (particularly in the 1980s and ‘90s) still plenty of live playing, as Page’s first book spotlights with photos of post-Zeppelin bands the Firm, Coverdale-Page, Page and Plant, and a variety of custom-made and modified new electric guitars, a topic explored in depth in the second book, the Anthology.

So unless you want to buy both books, or if you’re Christmas shopping for a Zeppelin addict, which one should you pick? For me, as a guitar fanatic whose interest in playing was partially inspired by Page’s roaring lead playing with Zeppelin, I’d have to go with the Anthology. It’s filled with new, artfully arranged and beautifully lit photographs of Page’s “guitar army” in all their glory. The subplot of Zeppelin’s concerts, particularly their later shows, was Page doing battle with his equipment — the Les Paul, the double-neck, the Danelectro, the acoustic guitars, the violin bow, the Theremin, and the Echoplex — and (usually) winning. And all that kit looks fantastic in the Anthology.

However, for someone who isn’t as big a guitar enthusiast, but wants an overview of Page’s career arc in photographic form, his first book might be the better option.

In both cases, while you’ll learn some interesting trivia along the way, as for the real dirt behind Page’s career, to invert Robert Plant’s lyrics on their epochal song “Kashmir,” none will be revealed.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member