"September 5," now out on Blu-ray and currently streaming on Paramount+, starts with the classic 1970s-era ABC TV logo followed by an expository montage with a chippy 1970s-style narrator telling the home viewers that the 1972 Munich summer Olympics were that city’s first since 1936, “a starting signal for a peaceful postwar Germany to share itself with the world.” The narrator beams with corporate pride, explaining the basics of how satellite TV works, and that ABC cameras are everywhere during the games, “including on the Olympic tower, which gives us a nice overview of the Olympic village.” Not coincidentally, as the montage explains how the images are being transmitted throughout the world, there is a brief shot of the World Trade Center in New York. (It’s a bit of an anachronism since construction of the two towers was not yet complete in 1972, but it works as a subliminal hint of the menace to come and as a callback to the ending of Steven Spielberg’s 2005 film, "Munich.")

Also not coincidentally, the montage ends with the firing of a starter pistol, the most benign use of a gun that will be seen in the film. The montage looks like something that the boffins at ABC Sports could have created in their sleep in 1972, but as the movie's editor Hansjörg Weissbrich told the “Art of the Cut” blog, “actually, it’s not a promo from the network. It’s pieced together by us. We had a couple of different options for the opening of the film, but eventually we felt that the best option would be to start with that promo to set all the important information up, like where we are, what it is about, that it’s the Olympic Games to be broadcast live… We wanted to also create a light tone at the beginning to set the stakes for what would follow.” The montage explains the mechanics of how the men who were covering a sporting event—a bit of light entertainment for the viewers back in the U.S.—would have to shift on the fly to covering the first terrorist attack ever broadcast live on television.

Once the montage is complete, the action then shifts to the men in ABC’s control booth in Munich, showing the basics of a live multi-camera shoot (in this case, of U.S. swimmer Mark Spitz versus his German counterpart) and how the director calls off which shot he wants to see next.

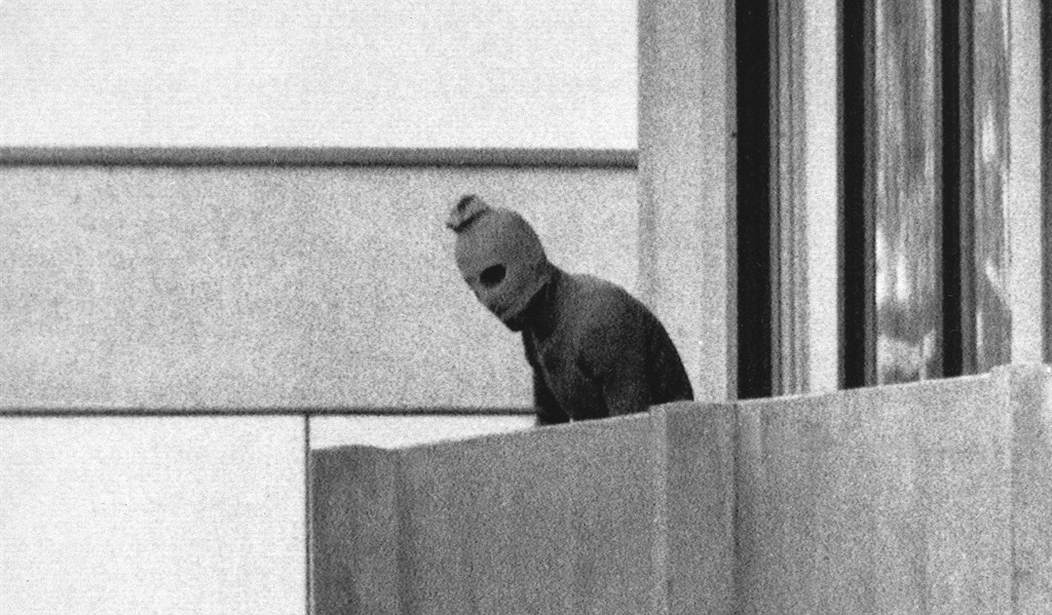

After the night crew winds down and begins to prep the control room for another day’s broadcasting, gunshots are heard outside the studio. The Palestinian terrorists are beginning their takeover of the Israeli quarters of the Olympic Village.

Budget limitations forced tighter, focused story

"September 5" exists because Tim Fehlbaum, its 42-year old Swiss director, wanted to make a film about the terrorist attack, but found that actually filming it would be far too expensive for the budget he could hope to raise:

The Swiss writer-director — he previously made two indie sci-fi films — started really big. He was going to capture from every angle that fateful day of Sept. 5, 1972, when eight terrorists from the Palestinian militant group Black September infiltrated Munich’s Olympic Village and attacked Israeli athletes, killing two and taking nine hostage. (All would end up dying.)

Police officers, Olympians, journalists, civilians, government diplomats — Fehlbaum and his co-writers Moritz Binder and Alex David would cut between them all, creating a Rashomon for the Olympic era. The seismic event — a brazen act of evil on the world’s biggest stage — demanded a big cinematic treatment. Fehlbaum would give it nothing less.

But then a little voice called financial reality piped up. “We had a script and I think it was quite good,” Fehlbaum says. “But I looked at Philipp [Trauer, his producer] and said, ‘How are we going to do this?’ There was simply no one who was going to trust me with the kind of budget we needed to make a movie like this.”

Film is what happens when ambition runs into disappointment. And Fehlbaum had just suffered a head-on collision.

The movie that would result instead — a 91-minute bullet train about media ethics titled September 5 — created a buzz out of Telluride, prompting an acquisition frenzy and vaulting to the top of THR’s Feinberg Forecast best picture list, where it continues to sit ahead of its limited release by Paramount on Dec. 13. But the road from there was filled with more speeding obstacles than the Autobahn.

Rather than “a big cinematic treatment,” the budget Fehlbaum could raise forced him to go small and intimate. He eventually found Geoff Mason, now 83, but in 1972, a young producer for ABC Sports who was manning the control room in Munich when he heard the first gunshots. Fehlbaum and his production crew would have marathon Zoom calls with Mason, who explained the logistics of live television in 1972.

Depicting a sharp contrast to today’s ubiquitous social media

And in today’s world of ubiquitous smartphones and social media, those logistics look absolutely primitive. Almost everyone now carries around in their pocket a camera capable of near-cinematic levels of detail. But in 1972, color TV cameras were massive devices and produced comparatively crude pictures. To supplant the basic images of talking heads and athletes in the stadiums those studio cameras were recording, ABC Sports also employed portable 16mm film cameras – film that needed to be developed in a lab. (When the crew cut to a commercial, the ad briefly shown is for a Kodak Super 8 movie camera, yet another once ubiquitous device that’s now contained within the iPhone and without the need to drop film off at Fotomat to be developed.)

The film's production design and props department do a brilliant job of recreating what would have been state-of-the-art, no-expense-spared network broadcasting technology in 1972, tacitly highlighting how crude and out of date that technology is today. A supporting actress in "September 5" has the full-time job of moving around white letters on a black background to create the names that would superimpose on top of each on-air reporter, a technique that would soon be replaced by increasingly sophisticated computer systems.

The actors’ interactions with period videotape footage of Jim McKay reporting from Munich in 1972 is surprisingly well done. Regarding the cast, the Hollywood Reporter notes:

Casting was its own challenge. Filmmakers needed actors who resonated with modern audiences but also brought an air of ’70s grit. Peter Sarsgaard, a quiet voice of journalistic authority in Shattered Glass, would play Arledge. “Actors like to act and show off, but the piece did not call for that,” Sarsgaard says. “There is a more potent form of authority — where you just know you have the power and don’t have to demonstrate it.”

British actor Ben Chaplin fit the bill as Marvin Bader, a real-life Olympics operations maven who as the son of Holocaust survivors carried some baggage into the control room; he says he identified with the tension of shouldering another’s pain as you also try to shed it. The film skates thrillingly not just through every logistical hurdle but every moral and character wrinkle, and Bader proved a fitting vessel.

German actress Leonie Benesch would be cast as Marianne — a young, dedicated production assistant who would not just serve as the linguistic link between the U.S. team and German locals but as a thematic fulcrum as well, representing a new fresh-faced Germany that in its futility to stop the attack is suddenly showing its wrinkles. She is a composite character, but Benesch notes that “the feeling that Marianne had of not being able to show that Germany was in a new place was very real.”

And then there was Mason. John Magaro was not an obvious choice — a workaday actor known for the violent-but-sensitive Vince Muccio in Orange Is the New Black and indie roles like Past Lives and First Cow. Then again, the real-life Mason was not an obvious choice either — a workaday type himself thrust into the spotlight. The match took, and the production had its Mason.

The real-life Mason was trying to make tough moral choices on the fly while also attempting to seize the moment, and Magaro latched on to the tension. “Geoff was trying to make his way in the business, and one way to do that is to lean into the sensational, while the other is to be a journalist in a pure form like Marvin Bader,” he says. “This gray area was a rich thing to play.”

Despite its retro art design, the producers couldn't have known how contemporary a movie they were making, as Judith Miller wrote in her review at Tablet:

The film was in post-production when Oct. 7 took place. Fehlbaum has said in interviews that no one associated with the film predicted that it would be released as Israel was reeling from this even more horrifying attack. But the Hamas terrorists had clearly absorbed the lessons of Sept. 5. They wanted their slaughter to be seen, virtually live, and celebrated. In fact, much of what we know about the massacre and abductions that day initially came from what the attackers themselves recorded, broadcast, and boasted about on their own social media. As such, a direct line can be drawn between the 1972 Munich Olympics, when ABC covered the terrorists, and Oct. 7, when the terrorists dispensed with their media intermediaries and recorded the slaughter themselves. Both generations of terrorists were performing for the camera. And as Fehlbaum clearly knows, viewers can’t look away.

But leftist critics and awards bookers certainly could. In September, Scott Feinberg of the Hollywood Reporter wrote up last year’s Toronto International Film Festival and noted:

But for the most part, the humdrumness of this year’s fest feels like the result of self-inflicted injuries — and not just the silly festival-exclusivity policy.

My understanding is that TIFF outright rejected September 5, which was the hottest sales title that played at the Venice and Telluride film fests — and, THR reported this morning, has landed at Paramount — ostensibly because it might generate controversy related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. So, fearing a backlash, the fest did not screen a film that is going to get a best picture Oscar nomination and maybe even win — it could have done so on opening night, which was, appropriately enough, Sept. 5 — but did screen Russians at War, a documentary that’s sympathetic portrayal of Russians involved in the Ukraine conflict did result in protests of such a scale that the fest ended up pulling the film.

The following January, Seth Mandel of Commentary described young leftists at the Brooklyn Alamo Drafthouse theater diving for the fainting couches when tasked with running "September 5" for audiences:

Many of its own employees, organizing under its union, were outraged. They petitioned their employers to stop showing the film. Alamo appears, as of this writing, to have ignored them.

But it’s the petition itself, which of course soon garnered signatures from all manner of local organizers, that has to be read to be believed. Calling the film “Zionist propaganda,” it reads, in part:

“Echoing the well-worn pattern seen since 9/11, September 5 is yet another attempt by the Western media to push its imperialist and racist agenda, manufacturing consent for the continued genocide and cultural decimation of Palestine and its peoples. It is quintessential Orientalism: Depicting Arabs and brown people as evil, antisemitic terrorists, while lionizing the very newsrooms that provide political cover and, in many cases, cheer for endless wars and genocide. We’re certain that Alamo’s quirky pre-show won’t provide this context.”

The movie “depicts” Arabs as “antisemitic terrorists”? The movie is about an actual event, in which Arab anti-Semitic terrorists carried out murderous acts of terrorism. What’s more, the film is about the coverage itself—because a fair amount of what happened was broadcast. People watched it. This was a historical event that happened, like the moon landing.

More from the petition: “We, NYC Alamo United, wholeheartedly condemn the Alamo’s willingness to profit off of the genocide of Palestine.”

So we have two principles undergirding the opposition to the film. The first is that literal history as it happened is “Zionist propaganda,” and the second is that any depiction of Israelis or Palestinians is “profit[ing] off the genocide of Palestine.”

Speaking of the moon landing, near the end of "September 5," when it looks like a happy ending is imminent, Peter Sarsgaard’s Roone Arledge says to Ben Chaplin’s Marvin Bader, that the president of ABC told him that more people watched their coverage of the Munich terrorists “than Armstrong stepping on the moon.” "September 5" feels very much like the mirror universe equivalent of Ron Howard’s classic "Apollo 13" movie from 1995. The mostly male characters in garish early 1970s togs and fat sideburns grimace around a minefield of television monitors in the hopes that the men they’re watching on their TV screens will survive their missions. We know how both stories will end (if you’ve made it this far, you know that "September 5" won’t end on a happy note), but it’s a testament to both films’ writing, acting, directing, and editing that both are thrilling, eminently watchable films. And from that perspective, and its sad and agonizingly contemporary theme, "September 5" is highly recommended.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member