Before we start, I need you to know that I'm not advocating for medically assisted suicide (MAS). I do believe that I grasp why some people, in rare and specific circumstances, view it as a deeply personal choice.

That belief comes not from emotion, but from watching the hardest years of suffering and listening to families stare at a future without mercy. As more states pass laws, including Illinois, which recently became the twelfth state to legalize medical aid in dying for terminally ill patients with strict criteria, the debate has grown far beyond politics, and into the core of how we treat the most vulnerable among us.

MAS raises essential questions: Who decides who is qualified? How do we protect people from coercion? What role should the government play at all?

These aren't easy matters, because they touch on autonomy, suffering, moral law, and the limits of state authority.

At the center of these laws are standards. In Illinois, for example, only adults with a terminal diagnosis expected to result in death within six months, confirmed by two physicians, may request medication that ends life.

The law requires oral and written requests, separated by waiting periods to ensure clarity. Physicians must tell patients of all other options, including palliative care and hospice. People who assist must not coerce or sway anyone to choose aid in dying.

Even with those rules, we need to ask who interprets them when the question turns grey. If fear, pain, or despair cloud a person's mind, is he or she capable of consent?

That's why some organizations, such as Dignitas in Switzerland, have a multi-step process. There, candidates travel to the facility, where mental health professionals assess their case; then they choose a day while they're clearly of sound mind to enact their choice. Decisions are repeated, verified, and only finalized when the person still has capacity and direction.

There isn't a single person who makes the call. Layers of checks protect against impulsive choice; their insistence on mental clarity prevents decisions made under duress or influence.

Should a Power of Attorney ever have the right to authorize MAS on someone's behalf? The short answer is no: A POA exists to manage affairs if someone can't act for himself or herself, but any directive that ends life and crosses a boundary that most legal systems and ethical guidelines maintain is out of bounds.

Only the person at the center of the decision can choose. If he or she doesn't have that capacity, MAS should be off limits, to protect the vulnerable from the misuse of power.

Different medical professionals feel differently. General physicians often focus on relief of suffering, and might support MAS for a person facing unending pain without hope of medical improvement.

Psychologists and psychiatrists tend to tread with caution; their daily work involves evaluating cognition, mood, and the potential for treatable depression. Many will agree to evaluation for competence, but resist any framing that normalizes ending a life as a solution rather than a last resort.

Palliative care specialists will argue for comfort, dignity, and pain management up until the last heartbeat, without assistance to hasten death.

Yet another aspect in this debate is religion. Catholic teaching, for example, views life as sacred from beginning to end. Any act that intentionally ends an innocent life, even to relieve suffering, remains morally unacceptable.

Other faiths differ. Some Protestant streams emphasize individual conscience under God. Judaism may allow withdrawal of extraordinary means, but it can be hesitant to endorse direct aid in dying. Buddhism places weight on intention; ending life carries heavy karmic consequences.

These perspectives shape how followers weigh MAS on both moral and spiritual grounds.

At a basic level, we have to define "quality of life." Is a life that can't improve still worth living? Who declares quality has faded?

In clinical settings, quality of life isn't a fixed number; it includes autonomy, pain level, cognitive awareness, and emotional connection. Calling quality "over" isn't a scientific measure; it's a judgment, and we need to be careful about imposing that judgment on others.

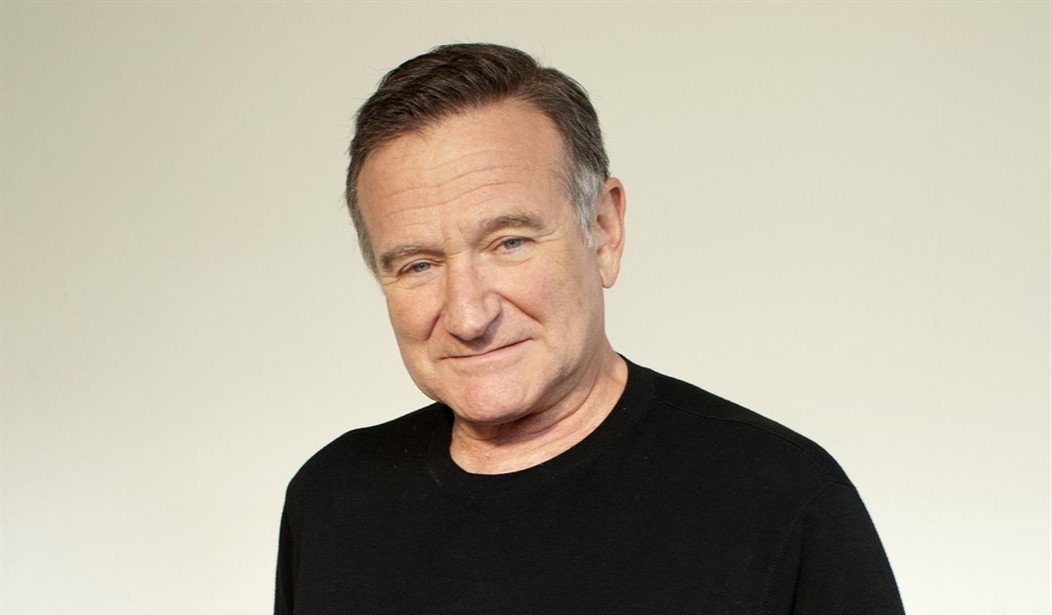

Robin Williams was suffering from Lewy body dementia, a neurodegenerative disease that causes severe cognitive decline, paranoia, depression, and hallucinations, often misdiagnosed in its early stages. As the disease rapidly worsened and stripped away his ability to think and function clearly, he died by suicide in Aug. 2014.

Robin Williams faced emotional torment and raw despair. His story reminds us that human suffering isn't easily quantifiable in a world where MAS becomes the default, under pressure to avoid suffering and to value efficiency over empathy.

Why, then, do some argue that MAS should be legal? A key reason is mercy, not shortcuts, and the desire to give people options when every other care path fails to ease suffering. If a person passes all safeguards and mental competency checks, many feel a moral society should allow choice.

Yet morality and legality don't always align. Our society balances individual rights with collective protection: Laws exist to prevent coercive death, because once states sanction ending lives on demand, society steps into dangerous territory.

Looking at the broader trend, MAS laws vary by state. Washington, Oregon, Vermont, and other states allow medically assisted death with strict criteria. They illustrate that each state defines boundaries within its culture and values.

A federal mandate would erase that local calibration. State's rights matter here, because local communities can decide whether and how to allow aid-in-dying. As in New Jersey, residency requirements stood up in court precisely because state policy holds the authority to make these weighty decisions.

I hope to add a little personal perspective. I've been close to psychologists and others who work with people's mental states. They've helped me understand why some feel MAS aligns with compassion when facing relentless decline, such as Lewy body dementia or unending pain. I can also understand why others recoil from that final choice, because they cling to the value of life even when every day carries injury and sorrow.

Both points have merit.

I've also seen how faith guides people through their toughest hours. Years ago, in Wausau, Wisc., a coffee shop owner chose prayer over medicine as their daughter faced her final days, despite her illness being easily treatable.

National commentary condemned them. I didn't, I can't judge what lies beyond another person's belief or God's call. To be Christian is to grapple with mercy and judgment, so look for the right path even when it confounds us.

In separate trials, the couple was found guilty of second-degree reckless homicide in 2009. The judge ruled that while the First Amendment protects religious belief, it doesn't necessarily protect life-threatening conduct. Wisconsin law exempts parents using prayer from neglect charges only if the condition isn't life-threatening.

The parents were sentenced to ten years' probation and six months in jail each, to be served in one-month increments over six years.

So where do I land? Not as an advocate, but someone who sees that MAS, carefully structured, may belong in rare and specific cases. I don't face terminal decline, or cling to each breath out of fear, but out of wonder at recovery and grace.

I believe that choice matters, that robust safeguards, mental capacity assessments, and personal autonomy should guide us.

The government shouldn't forbid a path when all criteria indicate that a person's decision is free and competent.

For sober discussion of life, law, and the boundary where choice confronts suffering, join PJ Media VIP and support writers who refuse easy answers.

Gain deeper essays and philosophical nuance. Sign up with promo code FIGHT.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member