[jwplayer config=”pjm_lifestyle” mediaid=”52327″]

Louis Farrakhan (approvingly) called it “Preparation for race war” while according to Brietbart’s Big Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino’s Oscar-winning film Django Unchained was “The Most Pro-Freedom Movie of 2012.”

Then there was Marc Lamont Hill, the intellectual mediocrity of a Columbia professor who gets dragged out of mothballs when a racial event reaches pop status, says something stupidly outrageous, apologizes or clarifies, then gets put away until the next time.

On a CNN panel about the ghoulish fan club for rampaging LAPD ex-cop Christopher Dorner, who counted among his victims the Asian-American daughter of a cop who investigated him, Hill said:

And, many people aren’t rooting for him to kill innocent people: they’re rooting for someone who was wronged to get a kind of revenge against the system. It’s almost like watching Django Unchained in real life. It’s kind of exciting.

Perhaps the most famous off-screen line about the film came from an opening Saturday Night Live satirical monologue from Jamie Foxx that riffed on “how black is that,”

I play a slave. How black is that? And in the movie I had to wear chains. How whack is that? But don’t be worried about it because I get out the chains, I get free, I save my wife, and I kill all the white people in the movie. How great is that? And how black is that?

But in the film, Django does no such thing. In fact, [SPOILER ALERT] he teams with a white guy whose moral outrage eventually gets the better of him, and gets himself killed (and without whose help, Django would have accomplished none of his heroics.)

I recently grabbed Django Unchained at a Redbox, and found it far less a compelling re-watch than it was as a first time experience in the theater (and less disturbing, having watched it in an urban multiplex where audience reaction was, at times, appallingly inappropriate). This movie relies so much on shock value and surprising choices (particularly musically) that the second time around, some of the anachronisms become much more annoying.

And since Tarantino himself brought up history…

Next: Django Unchained is much like the rhetoric that helped cause the Civil War..

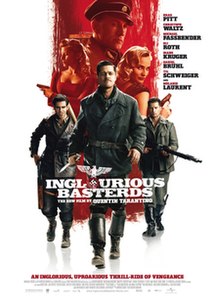

Look, nobody expects to go to a movie by a guy whose homage to The Dirty Dozen [SPOILER ALERT] showed WWII ending early because a group of avenging Jewish commandos were able to assassinate Adolf Hitler, along with much of the High Command.

So next to that, Django Unchained doesn’t mess with history much. After all, slavery happened, and it was really bad.

But Django Unchained really isn’t about history, like all of Tarantino’s work — other than his greatest movie Jackie Brown, a straight up adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s novel Rum Punch — it is about the movies.

The obscure Franco Nero 1966 Spaghetti Western Django, a movie so violent it was banned in Britain until the 90s, is, predictably, one of Tarantino’s favorites. But that movie about a fortune-hunting drifter bent on avenging his wife, who kills about half of the Mexican Army, shares little with this Django other than name, style, and a savage setting in a place that never existed.

Django Unchained really owes most to the Clint Eastwood classic The Good the Bad and the Ugly and the underrated must see James Garner/Louis Gossett Jr. movie Skin Game.

Like The Good the Bad and the Ugly, Django is filled with guns that weren’t invented yet, ammunition that wasn’t even thought of yet, and a “historical” setting that only exists in the movies.

Okay, if you want to do a “spaghetti western set in the South,” as the director says, it wouldn’t really work with muskets, but the hellhole plantation is filled with gunfighters with guns that were featured over a decade later at the OK Corral. Hell, even Tarantino didn’t give his WWII Jewish-American soldiers Uzis. Profanity and violence warning:

[jwplayer config=”pjm_lifestyle” mediaid=”52328″]

If the Confederacy had had Winchester 73s, they would have won the war rather easily.

Perhaps most significantly, and maybe damningly, is that Tarantino’s real inspiration for the setting of Django Unchained is another exploitation film, Mandingo, perhaps the prime example of the fetishization of black violence in pop culture history.

Mandingo and Django treat as fact the idea that slave owners staged fights to the death between slaves for their own amusement. Since the novel, its sequels, and the horrible movie adaptation, Mandingo entered the public consciousness in an almost subconscious way that has many Americans thinking this actually happened — at least somewhere.

This is, however, complete balderdash. And it’s not just Confederate apologists who say so. Even the most leftish of historians say there is zero evidence of such activity. They point to the obvious economic disincentives, and the fact that records of the era are remarkably detailed. Also, logically, for such a system to exist, many plantations would have to be involved, or it would be remarkably expensive for the participants.

Having just read Thomas Fleming’s remarkable A Disease in the Public Mind: A New Examination of Why We Fought the Civil War, Django Unchained reminded me of the kind of slander and wild stories put out by the Abolitionists to stir up war — both race and civil.

In my interview with Fleming, he discussed the over the top rhetoric in which all kinds of depravations were made up of whole cloth and presented throughout Northern churches as truth:

For the first half of the 20th Century, the abolitionists were recognized as one of the prime causes of the Civil War. Their current popularity is the result of the civil rights movement, which ignored their dark side. I was amazed — and distressed – when I encountered the virulence of their hatred. By the time the 1850s began, they preached a paranoid detestation of “The Slave Power.” They compared the South to Anti-Christ. Others said it was the apocalyptic dragon of the Book of Reveleations, rising to strangle freedom in the North as it had extinguished it in the South. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts summed up this fanaticism in a single sentence. “Are you for freedom or slavery?” he shouted to a Boston audience. “Are you for God or the devil?”

… The abolitionists’ goal was not persuasion of southerners. It was to shame them into submission, confess their guilt and free the slaves. It was essentially a fanatical religious crusade.

Next: Quentin Tarantino claims a murderous fanatic is the greatest American of all time.

In an interview on the Charlie Rose show on PBS, Tarantino was talking about his then recently released film Django Unchained with guest host director Richard Rodriguez. He revealed that his greatest American hero was… John Brown.

QT: I would one of these days love to do the John Brown story, he’s one of my biggest heroes of all time; and I’d actually like to play John Brown because I think I kind of look like him a little bit. But I’m actually thinking that may be the last movie I’ll ever make–I’ll be 59 or 60, I’ll look the right age, I’ll be the right age. And so, that’s like an Unforgiven thing–

RR: Why is he such a hero?

QT: Because he pretty much ended slavery all by himself. And like all great patriots, was tried for treason [laughter]. I mean he’s the only white man that’s ever earned a spot on black history calendars, alright, and there looking you in the eye. Nobody saw slavery the way he saw it, and “if we have to start killing people to stop this then they’re going to know what time it is.” I just love him. He’s just my favorite American.

But as Fleming reminded us, QT is not the first American writer to lionize Brown.

The best people of the North showered praise on a fanatic who believed that “without the emission of blood, there is no forgiveness for sin.” In Kansas a few years earlier, Brown had murdered six unarmed southerners before the horrified eyes of their wives and children, and ordered his sons to hack up their bodies with swords.

After Brown’s execution, America’s best-known writer, Ralph Waldo Emerson, declared him the equal of Jesus Christ. Another Massachusetts man told Emerson that compared to John Brown, Christ was a “dead failure.” He had ignored three decades of northern prayers begging him to end slavery. John Albion Andrew, the governor of Massachusetts, declared the South had to be conquered, “though it cost a million lives.”

But Brown was not just a bloodthirsty fanatic, he was also… an idiot. I have compared the praise of Brown by Abolitionists to the situation if pro-lifers were to laud an abortion clinic shooter. But it’s really worse than that.

Praising John Brown at Harper’s Ferry for his crusade to end slavery would be like praising an abortion clinic shooter who accidentally shot up a crisis pregnancy center instead of an abortion clinic.

Next: John Brown’s Moronic Revolution

John Brown’s decision to seize the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry was about as dumb a choice as any would-be guerrilla leader could make on several levels.

Harper’s Ferry was an almost impossible place to hold and defend, but thanks to railroad lines, an absurdly easy place for the authorities to reinforce quickly.

Brown’s “plan” was to ignite a race war, and hoped slaves would join in his fight. But Harper’s Ferry had almost no slave population,(88) had a large number of free black citizens (1251), and was generally known as a pretty tolerant place. The first man killed by Brown’s forces was Shepherd Hayward, a free black man, shot in the back trying to flee.

The next casualty was town mayor, Fontaine Beckham, a man particularly known for his sympathy and kindness to black residents of Harper’s Ferry. He had employed Hayward and was so distressed by his death that he carelessly exposed himself to fire from Brown’s men. Beckham’s will left money for another of his employees, a free black man, to purchase the freedom of his family who were still slaves.

Oops.

The man most people consider the Greatest American, George Washington, may have had questions raised about some of his military decisions, but he didn’t attack, say Concord, and kill a bunch of people sympathetic to the revolution…

So why is this important? Many reviews noted that the Mandingo fighting was a myth, but hey, slavery was really really bad, so who cares about a little exaggeration? While Tarantino certainly played with the facts of WWII, imagine if the director had proposed there was cannibalism at Auschwitz.

But the movie does not act as though this was something extreme or hidden, but an accepted and even widespread enough of a practice to have a circuit, complete with business agents, scouts and champions. (When actually, it would have been illegal.)

On the other hand, if a young person is convinced that this was typical slaveholder behavior, that all slaveholders should be slaughtered — and oh, by the way, a chunk of the Founders were slaveholders, and they wrote this Constitution you are told to care about…

Join the conversation as a VIP Member