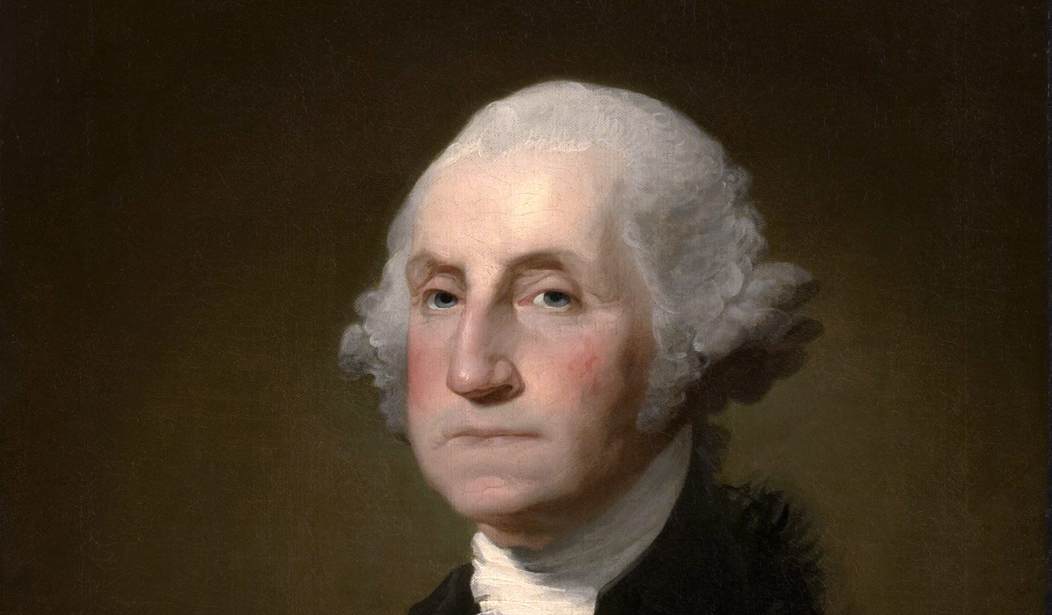

Writing a successful play is no easy task. When I was commissioned to write a play about the young George Washington several years ago by a California-based producer, I had no idea the project would take me into the dizzying orbit of “devised” or collaborative work.

Collaborative work is a tricky and dangerous terrain. After all, the expression, “A camel is a horse designed by committee,” didn’t evolve out of thin air.

This figure of speech takes a dim view of committees and group decision-making, at least when it comes to the incorporation of too many conflicting opinions into a single creative project.

“Too many cooks spoil the broth,” also sends the same message, that being: everything is spoiled if too many people participate in a single task.

There are exceptions, of course. Editors, I think, can work collaboratively, but it is an entirely different ballgame for writers. When an ex-New York screenwriter I know told me about her experiences as one of twelve—yes, twelve—writers for a TV sitcom, I wondered how a roomful of people like that could get anything done.

This friend told me that the writers would sit around a huge conference table with their notepads and pens, and that after scribbling lines of dialog, they would compare notes and brainstorm. After multiple revisions and discussions, they would brainstorm again and then vote on the best lines.

When the writing session was over, they would order take-out.

An excruciating process to say the least, for how do you get twelve people to agree on anything, much less a storyline for a TV sitcom? Twelve may be an apostolic number, but it’s too many brains for a smooth consensus. Think of the angst and tribulations that juries go through when it comes time to reach a verdict.

I had always thought of writing a play as a solitary endeavor, like the way novelist Thomas Wolfe (Look Homeward, Angel) wrote his novels on yellow legal pads standing up in his kitchen and using his refrigerator as a desk top. (Wolfe also had the rustic habit of submitting his manuscripts to his publisher in longhand).

Some writers, while not of a collaborative mind, are able to write in public. This is especially true of French writers. One has only to think of the artists who were able to concentrate in cafes like the Café Flores on the St.-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. Café Flores is where Jean-Paul Sartre wrote notes for his play “No Exit.” It’s also where Simone de Beauvoir, Sartre’s primary mistress (he had more than one) worked out many of her projects as well. On the other hand, the novelist Colette locked herself in her house in order to find the concentration to work. Marcel Proust (Remembrance of Things Past), however, was so noise-phobic that he wrote all day in a cork-lined room, surfacing only in the evening when he went out with his coachman.

As a student in Baltimore, I tried the writing-in-public thing, only I didn’t go to cafes but to the local Greyhound bus station where I wrote poems about the people I observed. There’s never a shortage of oddballs in bus stations. Mostly I felt like a poseur writing this way. Not surprisingly, none of the poems produced under the glare of a bus station security guard proved to be any good.

The start of my project for the California producer was like a honeymoon in Versailles. Although not a writer himself, the producer suggested reference books, trips to important Washington “hot spots,” conferences and lectures to attend in order to help improve my knowledge of the man. Problems at that time were minimal, and the future for the play looked bright.

Although the theme of the screenplay had been worked out and agreed upon in advance, in time the producer began to look at the theme as a moveable feast, at first suggesting very minor changes and then slowly going whole hog the way contractors do when they gut a house.

The work went from being a play about the first president of the United States to being an epic about slavery.

Eventually the producer brought in other people to add their own two cents. In the beginning, only one or two people were consulted but then the new voices included secretaries, personal friends, the UPS man, strangers met on elevators, trains, or in city restaurants. Some changes made to the play were necessary; and (surprisingly) not everything suggested by the chorus was bad. Parts of the play even showed signs of improvement. But this was true only for a short while because soon the play became unrecognizable, a kind of Tower of Babel with changing themes.

The play had been so worked to death it lost its focus and soul.

The new version of the new play now only asked the question: Was Washington a racist? Does he deserve to be written about as if he was a good guy? The slaves who had worked for Washington had heretofore been peripheral characters but now Washington was almost invisible. There’s nothing wrong with this if that’s the story you want to tell. The problem was that the story or the theme of the play kept changing depending on who the producer was talking to.

In the end, the credits under the play’s new title page were now a mile long: The Story of George Washington, a Play by Marge Dilworth, Frank Coffee, Jim Cohen, David Buster, Donald Barnhouse, Jeff Hunter, Peter O’Toole, Frank Conroy, Henry Miller Jr., Tom NcHale, Arlene Apposite, Paul Goodman, Berry White, Bill Cosby Jr., Amanda Fox and (by the way)… Thom Nickels.

The title page alone reminded me of those short “sound bite” news stories written by four journalists.

Discouraged, I did some research and discovered that “devised” work in the theater is the latest avant garde infection. A noteworthy champion of “devised” work is David Dower, Associate Artistic Director at Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage. At a panel discussion once, Mr. Dower proclaimed, “The future of theater will be made by devised work,” and that “the days of one writer sitting alone in a room, submitting the play to the theater,” are over.

Huh?

Arena Theater, for instance, has a new “devised” policy of accepting plays from playwrights whom they “engage” with, meaning if you are a playwright outside their professional circle, you don’t stand much of a chance.

Michele Volansky of Philadelphia’s PlayPenn wrote about Mr. Dower in a past issue of PlayPenn’s newsletter and voiced a”‘wait and see” view about devised work, giving it the benefit of the doubt while also wondering about some of its more radical expressions, such as a play without a written text.

“For a play to endure,” she wrote, “you have to have a text.”

A text! How revolutionary!

As for the “devised” concoction of what once was my play, I can only compare it to man-made satellites shot into space. A satellite, of course, is made by a community of builders—a committee—so that there’s some likelihood that it will not crash to earth.

Plays, however, are not mechanical devices but creative projects that depend on a single artistic vision. That’s why the producer’s group of engineers posing as playwrights could not prevent The Story of George Washington from leaving its orbit and crashing to earth.

And crash and burn it did, as this particular story of George Washington was never heard from again.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member