President Trump spent one of his final days in office visiting a section of the border wall at Alamo, Texas.

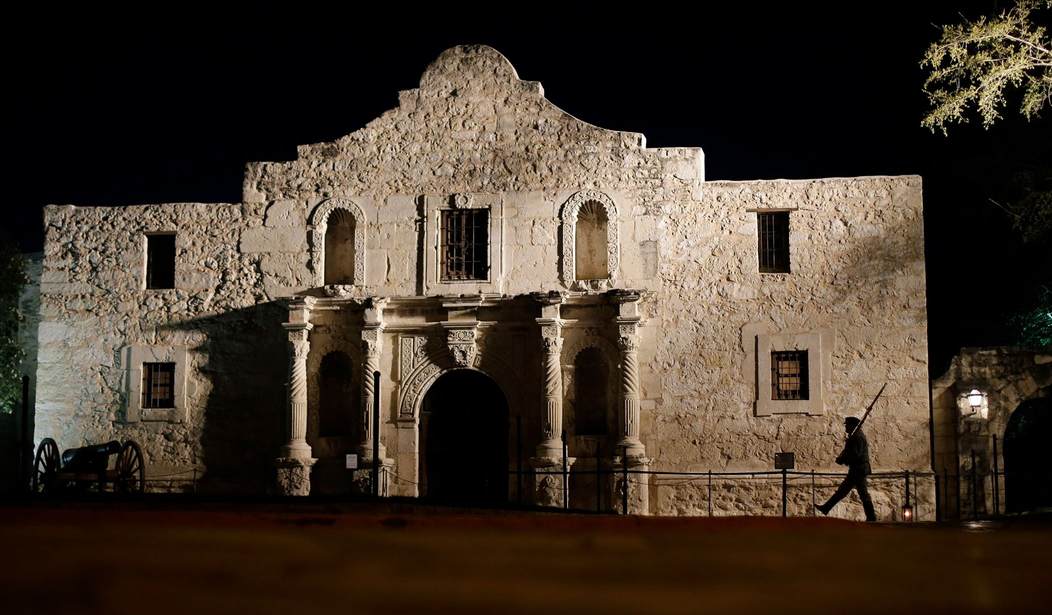

Most folks outside Texas don’t know there’s such a place as Alamo, Texas — a town, not the battle site. The town — Alamo, Texas — is about 240 miles from the Alamo itself, which is situated in the heart of San Antonio, which is also known far and wide by the nickname “Alamo City.” Because that’s where the Alamo, formerly known as Mission Valero de San Antonio when it was founded about a century before the battle, is located.

To be fair, there are many Alamos all over Texas. Buildings built to look like it. Companies with names like Alamo Plumbing. Alamo Rent-A-Car is all over the world. John Wayne built a large-scale Alamo set for his famous 1960 movie out in Bracketville, which still stands though it’s rapidly decaying. Because it’s out in the country, it’s striking that it retained a semblance of a compound lending it a more authentic period look than the modern Alamo, of which probably 75% has been lost to the growth of the city around it. At any rate, Texas is not short of Alamos or opinions about the Alamo.

USA Today decided Trump’s trip to the border town 240 miles from the Alamo was the right time to publish a one-sided piece on the famous Battle of the Alamo, which many on the left have decided to make infamous. If the New York Times was involved it might be called the 1836 Project. USAT sought out a couple of university scholars, both of whom rendered the now politically correct verdict that the Alamo Defenders, indeed the whole of the Texas Revolution itself, had more than a tinge of white supremacy about it. One of the scholars even smeared the Alamo as a monument to the Confederacy.

[Jorge Canizares-Esguerra, professor of history at University of Texas-Austin] said Mexican troops under President General Antonio López de Santa Anna were not coming to take freedom from the Texans but rather to liberate slaves on east Texan plantations. He called the Alamo “the largest statue to the Confederacy in this country.”

If that’s the case, William B. Travis et al. had a time machine.

The Texas Revolution occurred about 25 years before the Confederacy was a thing. Sam Houston opposed secession as governor of Texas, for what that’s worth, and all he did was win the Texas Revolution at San Jacinto and serve as the Republic of Texas’ first president. And while slavery was the primary issue sparking the Civil War — it had been the subject of wrenching debates even during the American Revolution, which wasn’t about slavery, and it had been the subject of the Compromise of 1850 that kicked the can down the road a piece — slavery was not the prime mover in Texas. It was an issue, it just wasn’t the issue. The writings of the Texians themselves make this clear. They were fighting for the same rights they had enjoyed under the American Constitution. Not just the right to own other human beings, though many did, unfortunately, favor slavery, but the rights enshrined in the Bill of Rights.

David Crockett even took this a bit farther. When he entered Texas he had to swear an oath to the Mexican government. Crockett, aware of what was happening across Mexico, actually changed his oath, so that he only swore to live under a “republican form of government.” That’s what the United States had, but Mexico, under dictator Santa Anna was in real danger of losing. Santa Anna had ditched local and state lawmaking and amassed power unto himself in remote Mexico City. This sparked rebellions not just in Texas y Coahuila, but in nearly a dozen other states across Mexico.

That’s important. Texas was not alone in attempting to break away from Santa Anna’s rule. That fact alone suggests the fight in Texas wasn’t some assertion of “whiteness” or even slavery. Native Mexicans revolted against Santa Anna in huge numbers.

Another important point to make is that all this took place during a time in which a wave of revolutions was sweeping across the world. Where it all would stop, no one knew. To oversimplify things a bit, there were two major arguments contesting for the future: limited government of the people through representative republics, or some form of dictatorship in the hands of the likes of Napoleon. The ripples begun by the American — republican — Revolution and the French — Napoleonic dictatorship — Revolution were still playing out. It could be argued that they still are. Look at Venezuela versus, say, Colombia. Or look at the arguments animating Washington.

The Texians themselves, mostly Americans and some Europeans, entered a Mexico that was already at the Federalist vs. Centralist crossroads. Jim Bowie, for instance, moved to Texas in 1830. That’s also important. Bowie’s wife, Ursula Veramendi, was the daughter of the Tejano governor of Texas. When she died during a pandemic in 1833, Bowie was heartbroken and never quite recovered.

Here’s the thing. The main argument in 1830s Mexico, of which Texas was then a part, concerned how powerful the government would be. Mexico was then just a little over a decade from tossing out the Spanish crown. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna was a war hero who started out championing Federalism similar to the American system — some power in the federal government, a lot of power for the states and localities. Because of this, even the Texians, including Bowie, initially saw him as an ally. A Federalist Mexico would presumably protect individual rights similar to the way they were protected in the United States.

The troubles in Texas didn’t start in 1835 or ’36. The first battle relevant to this discussion actually took place in 1832 (there was a very large battle years earlier), when the Mexican government attempted to disarm Texians and Tejanos in Nacogdoches, way over on Texas’ eastern border. Santa Anna was still a likely ally to the Texians—at that point a Federalist. But once he became president, in 1833, he betrayed the Federalist cause and switched to the Centralists, making himself dictator. That’s important. That’s when things went cattywompus and rebellion broke out all over — not just in Texas. It’s worth noting that Santa Anna knew what he was doing. It was no accident at all that he styled himself the “Napoleon of the West.” That was a nod to his high opinion of his military prowess, and what direction he thought Mexico’s government ought to take. Basically, his way or no way.

Santa Anna’s betrayal matters, though it doesn’t come up in USA Today’s story. It had a significant impact on the Texians’ and Tejanos’ view of him and on the course of history. Had he remained a Federalist, there likely would have been no Texas Revolution and no Battle of the Alamo.

The Battle of the Alamo itself followed the Texians’ and Tejanos’ major victories in the 1835 Battle of Gonzales and the Siege of Bexar. The March 6, 1836, defeat — and Santa Anna’s bloodcurdling treatment of the defeated there and at Goliad — became the rallying cry that galvanized all of the revolutionaries. The Alamo was the turning point in the war, important from then forward, though it was a heavy defeat that resulted in the loss of two of the most famous celebrities of the time — David Crockett and James Bowie.

So the Alamo was important in the grand scheme of things, very important, when it happened in the context of the war and afterward as Texas settled. If Texas State Historical Association chair Walter Buenger really told USA Today that the battle was “tactically insignificant” and unimportant until around 1890, then either he or the paper did the battle a disservice. It was arguably the turning point of the revolution. It’s possible Buenger’s thoughts were truncated or distorted. It happens.

This is also important: The last man standing to defend the Alamo during that horrific battle may not have even been Anglo. This can’t be proven, of course. But the evidence is suggestive that the last defender was Tejano.

The last defender may well have been Jose Toribio Losoya. He was born under Spanish rule, in the Alamo when it was both a garrison and a neighborhood. He became a Mexican during that revolution, and then sided with the Texians under threat of execution when the Texas Revolution began. Losoya, like his friends and neighbors who perished in the Alamo with him, was fighting for Federalism. So were Juan Seguin, Damacio Ximinez (the last confirmed Defender discovered, who helped Travis bring a cannon to the fort), and the other Tejanos who died fighting Santa Anna or survived the war as Seguin did (only to be smeared by pretty much everyone later). Losoya’s body was found just inside the doorway of the famous Alamo church (the building most people think of as “the Alamo”). If there was a last stand, that’s probably where it happened. Losoya could well have been the last defender fighting for the cause, a Tejano, resisting Santa Anna’s troops.

Losoya was fighting for his home, certainly, and he was fighting for the universal ideals of the Federalist cause espoused by the Texians who died alongside him. He wasn’t fighting for slavery and certainly not “whiteness.”

I do realize that we have the luxury of space here that a paper such as USA Today does not. We can include more nuance, more twists and turns. These nuances and twists are very important. The reading of history today is being warped and bent toward a modern fad, pushing everything through the trendy but toxic lens of critical race theory. This removes numerous key facts and mangles the story. This is unfair to history and the future.

Here’s another fact that doesn’t get a lot of airtime: Texas’ first vice president, when it was a country, was Lorenzo de Zavala — a well-educated Tejano physician and active Federalist leader. He and Losoya and other Tejanos really do deserve more airtime. It’s a pity that the Alamo has no place to tell their fascinating stories.

Here’s a bit of de Zavala’s, according to the organization that Buenger chairs:

Named by President Antonio López de Santa Anna in October 1833 to serve as the first minister plenipotentiary of the Mexican legation in Paris, he reported to that post in the spring of 1834. When he learned that Santa Anna had assumed dictatorial powers in April of that year, Zavala denounced his former ally and resigned from his diplomatic assignment. Disregarding Santa Anna’s orders to return to Mexico City, he traveled to New York and then to Texas, where he arrived in July 1835. From the day of his arrival, he was drawn into the political caldron of Texas politics.

Indeed he was.

The Alamo suffers today from the fact that it still has no proper museum to tell this complex story. It has never truly had one. This didn’t have to be the case. There was a project recently that would have changed this. I was part of that project for a while and was stalked and threatened by a militia group and smeared for the effort. Conspiracy theorists and misguided opportunists managed to kill that project, injuring the Alamo for decades to come if not forever — and leaving the field to those who wish to re-write the Alamo story and damage its reputation. That’s important, too. The state agency that oversees the Alamo has gone the way of Fight Club and decided not to talk about the Alamo.

The loss is Texas’ and the world’s. The Alamo and the Texas Revolution changed the map and the fate of North America. That story has yet to be told.