When I started writing this piece, China had just moved troops into the disputed border with India on its western frontier. So this piece was mainly about that. But events kept moving fast, in Hong Kong, Beijing and then Taiwan, when China threatened to use force against the island a little over 100 miles off its coast. China is now making serious threats on both its eastern and western flanks, and we have arrived at the anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.

Prior to the past week of riots in the U.S., communist China inserted troops into the disputed border zone with India in an area called eastern Ladakh. This territory runs along the border, called the Line of Actual Control, between the two Asian powers.

India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has begun building roads and bases in the mostly undeveloped region, but in areas India says are not in dispute. It says its actions are all happening clearly on the Indian side of the LAC. China, according to reports, has moved troops across the LAC border in the disputed area, onto Indian territory. Chinese military planes are showing up on Indian radar.

This is one of China’s most provocative actions against India in recent years. India’s reaction has been muted so far. Modi met with his top military staff and discussed the incursion, but India has not issued an official comment. This is as close to a comment as New Delhi has given:

“China’s strategy to put military pressure on India will not work. We want restoration of the status quo along the LAC,” said an official on the condition of anonymity.

It’s worth pointing out, the disputed area runs along the current Indo-Chinese border, meaning the border between India and Chinese-occupied Tibet. Prior to 1949, China and India did not share a border. Tibet was the large buffer state between them. Neither was much of a global force prior to 1949. India and China were weak regional states with more cultural than military or economic influence. India only became independent of British rule in 1947.

Today’s world hardly resembles the world before 1949. India has become one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. China is the world’s fastest-growing economy, or it was prior to the coronavirus pandemic. China is making aggressive moves from its eastern coast to its western frontier, and globally through its Belt and Road initiative (which is really a debt trap for developing countries).

What’s remarkable about China’s moves is that it is acting simultaneously on multiple fronts, even as its economy has been weakened by the coronavirus outbreak. China’s economy contracted in the first quarter of 2020 for the first time in nearly a decade, and it is no longer issuing an economic forecast for 2020.

But while China’s economy supposedly suffers, it is engaging aggressively in the South China Sea, notably by constructing islands and fortifying them. It is clamping down fast and hard on Hong Kong, threatening to end the “one country, two systems” setup it has lived with since 1997. While it has one eye on free and democratic Taiwan to its east, China is moving troops into the disputed territories on its western frontier with India (via Tibet). Is China setting itself up for major conflicts on both of its flanks? Is it assuming no one will dare stand against it?

The Forgotten Illegal Occupation of Tibet

If you’ve guessed from the above that China’s moves with regard to India involve Tibet, you guessed correctly. Most are aware of the disputed territories, Jammu and Kashmir, that lie on India’s western frontier. We tend to think of the dispute as being between India and Pakistan, and that’s not incorrect. India and Pakistan have fought skirmishes and wars over the territories.

But the border dispute also includes a third party, China, in Ladakh, which is east of Jammu and Kashmir.

China entered the border dispute thanks to its invasion of Tibet in 1949. After World War II, Mao Zedong led the communist takeover of mainland China. The nationalists, led by Chiang Kai-Shek, lost the war and retreated to the island of Taiwan, which lies about 112 miles off the mainland’s eastern coast. Over the decades, Taiwan has developed from dictatorship to democracy, while the communist mainland maintains that it has the right to own Taiwan, citing historical ties between the mainland and the island.

Taiwan enjoyed international recognition as the Republic of China up to the 1970s, when President Richard Nixon “opened” communist mainland China. President Jimmy Carter formally moved U.S. recognition from Taipei, Taiwan to Beijing, China, in Dec. 1978. Through the decades since, Republican and Democratic presidents have tilted toward Beijing while also maintaining a defense relationship with Taiwan.

Rewinding a few decades, China’s civil war began in 1948. By 1952, the communists had consolidated mainland control. In 1949, China invaded Tibet. Similar to its claims on Taiwan, China cited history in a self-serving way. Taiwan has long had historic cultural and economic ties to mainland China, but it was rarely under any mainland government’s direct control. The same can be said for Tibet.

Historically, Chinese empires and emperors had trade and military relations with Tibet, but Tibet was a large independent nation for most of the past 2,000 years. It formally declared independent status in 1913, decades before the communist takeover in China. The Dalai Lama was both Tibet’s religious and national head. Tibet maintained its own culture, languages, and religion distinct from China for millennia.

The Chinese invasion was over quickly, as China’s military easily overpowered Tibet’s small 40,000-man army. By 1950, China had consolidated control over Tibet and the world had little choice but to accept it as a fact while denouncing China’s illegal invasion and the brutal suppression and occupation of the Tibetan people. The current Dalai Lama lives in exile — in India. That’s one of the sore points between India and China.

“Free Tibet” was once a human rights rallying cry on the left, up to the late 1990s. But as China has grown wealthier, the cry to free Tibet has gone quiet. You’d be hard-pressed to find a human rights activist on any college campus today who knows much about the Tibet invasion and occupation at all, but they know about Israel and the Palestinians.

Why Did China Invade Tibet?

China’s invasion and occupation of Tibet are, according to Beijing, about reuniting China’s historic territory. The real reason China invaded Tibet is much more hard-nosed: to seize its land and resources.

If Tibet was the free and independent state it was prior to 1949, it would be the world’s 10th largest country territorially, but one of it smallest by population, with just over 3 million people.

Tibet is rich in natural resources, with significant deposits of copper, gold, silver, lithium, zinc, chromium, and uranium among other resources China and all modern economies need. Today China mines Tibet extensively, but native Tibetans have no voice and do not profit from China’s exploitation of their land.

Companies close to Beijing conduct all of the exploration and mining, and the mineworkers are imported from China. China transfers the minerals to its own industries. Simply put, China is squatting on Tibetan land in order to extract monetary and strategic value without any regard or compensation for Tibet’s people. China has treated Tibet in this way for 70 years, with less and less criticism from the outside world.

In 2018, the South China Morning Post (which is based on Hong Kong but has become pro-Beijing over the past few years) wrote that Chinese mining in Tibet could become another flashpoint between China and India.

People familiar with the project say the mines are part of an ambitious plan by Beijing to reclaim South Tibet, a sizeable chunk of disputed territory currently under Indian control.

China’s moves to lay claim to the region’s natural resources while rapidly building up infrastructure could turn it into “another South China Sea”, they said.

That was prescient. It may also have been a warning. “South Tibet” is Beijing’s name for some of the disputed territory between itself and India, on the eastern edge of Bhutan. In the last few years, Chinese passports have included not just Tibet, but also the disputed “South Tibet,” in images of China’s territory. Those passport maps include Hong Kong and Taiwan, too.

China masks its territorial ambitions in history, but it’s really focused on establishing prestige, consolidating resources and defensible borders, while crowding out rivals. Hence, the moves against Hong Kong, in the South China Sea (which is really about controlling trade and strategic routes), against Taiwan (prestige, trade and military value) and on the Tibetan border (minerals, border and pushing out India). It’s all a matter of prestige and the pursuit of national interest and power politics.

India vs. China

India and China are both very different in status from where either was just a few decades ago. In that time, China has become the world’s second-largest economy and its fastest-growing, along with becoming the world’s manufacturing hub.

China has gone from backwater to world power so quickly that much of the world hardly noticed until it was too late, but it is now an ideological, strategic and economic rival to the United States.

China’s central role in manufacturing has become painfully clear during the coronavirus pandemic. China reportedly hoarded medical supplies while it covered up the outbreak in the early, critical days. This tactic may return again in future conflicts.

China’s view of the world is deeply ethnocentric, seeing itself as the world’s rightful central power. It sees the centuries during which other powers have been ascendant, from the Russian czars to the Empire of Japan to the British Empire and the American centuries as aberrational, glitches in a system in which China should have been the axis around which the whole world ought to turn.

China has used its wealth to build a very strong military with blue water capabilities for the first time in modern history, an air force and a space program that is now planning missions to the moon and Mars. The latter are primarily prestige programs, just as China’s infamous lab in Wuhan is. They are about achieving prestige parity with the United States to eventually surpass and supplant it.

China also uses its wealth to fund propaganda campaigns and centers worldwide, including “Confucius Institutes” on school and university campuses across the United States. China uses its wealth to subvert American interests on our own soil, the latest example is former ambassador to China Max Baucus. Baucus has become China’s paid representative in the U.S. and worldwide media and politics. Just Google “Max Baucus China” to find examples like this and this. On Bloomberg TV recently, Baucus said Beijing would prefer Democrat Joe Biden to President Donald Trump in this fall’s elections. How many other prominent Westerners in politics and media are on China’s payroll?

China’s economic might became a weapon to silence American supporters of the Hong Kong democracy protests in late 2019 and early 2020. Beijing canceled pre-season NBA games and events when just one major NBA figure voiced support for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protesters. Beijing was easily able to use its dollar power to chill free speech on American soil, among wealthy sports owners, coaches, athletes, and media, despite our historic defense of free speech.

China has used the past few decades to lay the groundwork for it to surpass the United States and become the world’s dominant power. Human rights worldwide would die should that ever happen. China’s communist oligarchy does not abide dissent or criticism at all. China controls the Internet within its borders, with help from Western technology giants who also use Chinese citizens in the United States on H1B visas to displace American workers.

The Disputed Border Regions

On the Tibetan border with India, China certainly wants to extract all the minerals it can, without any regard for environmental impact, as it has done for decades. It also wants to assert its dominance over India as a regional and global power as both have risen, but with asymmetrical growth heavily favoring China.

India is one of the few Asian powers capable of challenging China on the continent they share. Whether India ever will challenge China is another matter, but it is one of the few regional powers that really could. Both understand this; one of India’s military bases outside its own territory is in Cam Rahn Bay, Vietnam. India monitors the South China Sea from that base. Vietnam, nominally communist, defeated China in their 1979 war and has become increasingly capitalist since the 1990s. Today Vietnam’s top trading partner is the United States, followed closely by China.

One might think of Russia as another potential regional rival to China, but the two are probably less likely to engage in combat now than probably any time since the end of World War II. The fall of the Soviet Union removed their communist intra-ideological rivalry. Russia simply has far fewer people and a much smaller economy than China, and other than oil it has fewer valuable natural resources.

Tibet, on the other hand, not only is rich in minerals, it may be rich in oil. China has been exploring Tibet for oil for several years.

Tibet is definitely rich in water. This map on Free Tibet (admittedly not an unbiased source) makes that plain. Three of the region’s most important rivers, the Mekong, the Yangtze, and the Yellow River, and several others all originate in Tibet before flowing into other countries. China dams these rivers to generate electricity that it uses to power its own industries and cities.

At Home and at Harvard, Communist China Runs the Ultimate Cancel Culture

It also can use these rivers to control water supplies in Vietnam, Thailand, Burma, Laos, Cambodia, and Bangladesh. By controlling Tibet, China can starve several of its potential regional rivals of one resource humans cannot live without.

Does anyone want to bet China would not strangle these countries — or at least threaten to — if it deems such actions are in its interests? Should war break out between China and a rival — India, the United States, Japan, practically anyone — Tibet’s water would swiftly become Beijing’s leash keeping its southeast Asian border states in line.

Such action might cross the line into war crimes, but China’s occupation of Tibet is illegal and its treatment of the Uighurs and dissenters is brutal and inhumane. China hoarded medical supplies during the early coronavirus outbreak, then shipped faulty equipment overseas as countries suffered from the outbreak China failed to control.

China is the world champion in mass murder, worse than the Soviets and even the Nazis — combined. Communist China’s founder, Mao Zedong, led the world’s worst mass starvation and killing campaigns in human history, the Great Leap Forward (1958-1963, 45 million estimated deaths), and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976, estimated 20 million killed). Mao was directly responsible for history’s worst and most tragic mass killings. His communist descendants regard him as a hero and are no more enamored of human rights or life than he was.

The Stakes in the Disputed Territories

As we look at today’s India and today’s China and the moves along the LAC, the differences are very clear and the stakes are very high. China is the world’s most populous country; India is second. China has the world’s second-largest economy and its second best-funded military; the United States remains first in both of those categories. India is the world’s second-most populous country. India boasts the world’s fifth-largest economy, with Japan at number three.

Globalists engaged China and gave it favorable trade deals and status on the theory that a wealthy China would become a democratic China and during the Cold War, would be a counterweight to the Soviet Union. That has not happened, instead, China has become more repressive at home and more aggressive abroad. But perhaps the globalists’ theory that has failed in China has worked in India.

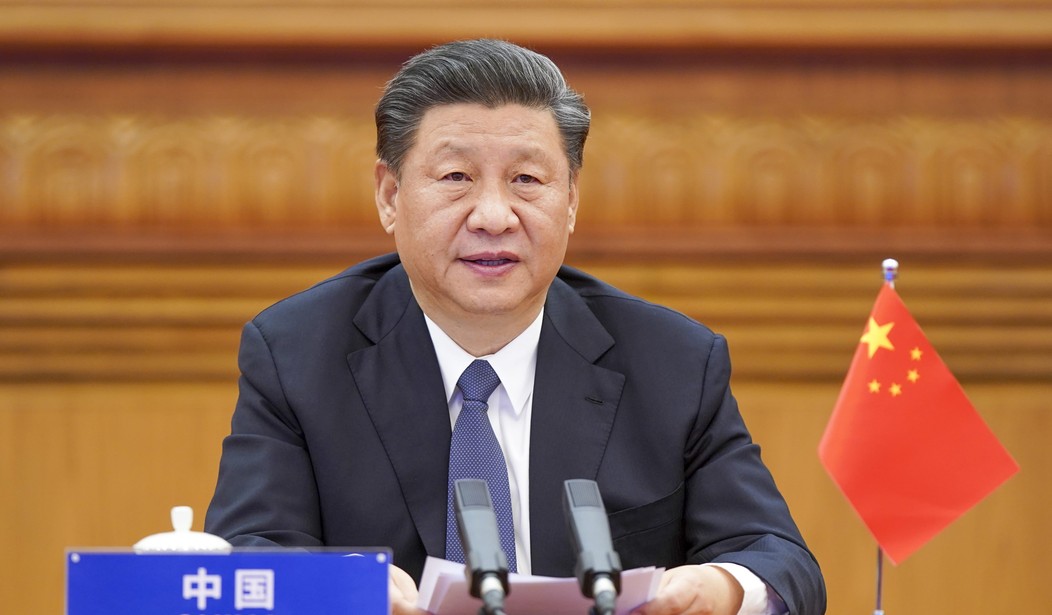

Both India and China are nuclear states. Their interests have become increasingly divergent in recent years as India has become more democratic and China, less and less. Both India’s Modi and China’s Xi are pursuing their perceived national interests abroad and in the disputed territories. But where China is becoming more aggressive with multiple regional and global rivals, India is intentionally warming up its relations with the United States, Israel, Japan and other open societies.

Multiple Fronts and the Near Future

As the Hong Kong story moved quickly, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that China’s moves against Hong Kong mean the city-state is no longer autonomous. The following day, Beijing approved the so-called security laws regarding Hong Kong, effectively proving Pompeo right. After China approved the new laws, the United States, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom issued a joint statement condemning the move.

China has of late tried to bully Australia away from its close relationship with the U.S., to no avail so far. Key U.S. ally Japan is also “seriously concerned” over China’s treatment of Hong Kong. South Korea, the pro-Beijing South China Morning Post writes/warns, will have to choose between China, its largest trading partner, and the United States, its military and strategic partner. The world economy depends on a free Hong Kong. China’s moves were never going to pass unnoticed.

Either Congress or President Trump could react to Pompeo’s report on Hong Kong’s status, triggering a legal change in its special status. This would have sweeping effects on trade and travel. Hong Kong is currently the world’s main conduit to fund business in China, and China’s main conduit for funds going out to invest worldwide.

That’s due to Hong Kong’s respect for the rule of law and generally accepted business practices. China is less dependent on Hong Kong than it was a few years ago but the city’s unique status is still key. If China cannot move investments through the city, those investments may not happen or go elsewhere, such as Seoul or Tokyo. The world has begun divesting from China during the trade war and the coronavirus pandemic. Hong Kong’s fall could be expected to speed this up.

The question behind all of this, is why is China acting against India, Hong Kong, the South China Sea, and Taiwan all at once? It seems foolish to provoke so many issues against so many strong adversaries at the same time.

War is a test of wills. While China’s actions have not sparked war yet, any or all of them could. China is not behaving as if any or all of the possible consequences for its actions, including war, are of any great concern. It’s behaving as if it simply does not know how to behave, but this is a calculated stance. Some of China’s actions may be mere distractions from its true goal. It’s clearly testing the world’s will over Hong Kong. A war with India is less likely to trigger U.S.-led military reaction than assaulting Taiwan would.

China’s multi-front belligerence suggests some possibilities: that China believes it is strong enough to handle major conflicts on multiple fronts now in relation to any of its potential adversaries; it believes it has a very short window during which it has the relative strength and opportunity act without triggering severe consequences; or it believes the U.S. and its allies (and India) lack the will to stop it.

While the China crisis was heating up, the George Floyd protests devolved into street riots and violence in about two dozen American cities, violence led by the international terrorist group antifa. How does a United States that is at least temporarily preoccupied with serious internal violence and deep division in an election year impact China’s strategic decision-making? Was this already baked into China’s strategy?

Time will tell. And possibly, not very much time.

Bryan Preston is the author of Hubble’s Revelations: The Amazing Time Machine and Its Most Important Discoveries.

Without Communist China, Would Palestinian Terrorism Have Become Such a Menace?