Every time something controversial happens in American politics, there are always people who want to pronounce it "treason."

See, for example:

Wouldn't this be treason by Mark Milley? pic.twitter.com/iqOrOHKFeM

— Gain of Fauci (@DschlopesIsBack) January 14, 2025

and this:

Treason and money laundering.

— GABRIEL 🪽 (@TheGabriel72) January 16, 2025

She makes a great point. However, it makes me sick hearing how the government spends our tax dollars while I work a full-time job, at a 100 plus hours every 2 weeks and I'm still struggling to buy groceries, pay my utilities and pay my mortgage. pic.twitter.com/hYwf1JDo0b

It's certainly not limited to the Right.

Nor did Trump escape accusations of treason.

The Founders were well aware — only too well aware — of the risks they had taken by starting the Revolution. As Ben Franklin is supposed to have said, "We must all hang together, or we shall assuredly hang separately." After all, it was only a hundred years or so since Henry VIII had taken heads left and right on accusations of treason for reasons as various as disagreement over his dissolution of the Church to an indelicate but effective means of divorce.

The Founders were well aware — only too well aware — of the risks they had taken by starting the Revolution. As Ben Franklin is supposed to have said, "We must all hang together, or we shall assuredly hang separately." After all, it was only a hundred years or so since Henry VIII had taken heads left and right on accusations of treason for reasons as various as disagreement over his dissolution of the Church to an indelicate but effective means of divorce.

While the penalty for treason was by then hanging rather than beheading, it was nonetheless very fatal.

In the Federalist paper number 43, Madison (writing as Publius) said:

But as new-fangled and artificial treasons have been the great engines by which violent factions, the natural offspring of free government, have usually wreaked their alternate malignity on each other, the convention have, with great judgment, opposed a barrier to this peculiar danger, by inserting a constitutional definition of the crime, fixing the proof necessary for conviction of it, and restraining the Congress, even in punishing it, from extending the consequences of guilt beyond the person of its author.

Honestly, it seems pretty clear in the Constitution and even clearer when you look at what the Supreme Court has said in, for example, the ex-Parte Bollman decisions and in Aaron Burr's treason trial — in which he was acquitted, of course. The congress.gov site expands further:

The Treason Clause is a product of the Framer’s awareness of the numerous and dangerous excrescences which had distorted the English law of treason. The Clause was therefore intended to put extend[ing] the crime and punishment of treason beyond Congress’s power.1 Debate in the Constitutional Convention, remarks in the ratifying conventions, and contemporaneous public comments make clear that the Framers contemplated a restrictive concept of the crime of treason that would prevent the politically powerful from escalating ordinary partisan disputes into capital charges of treason, as so often had happened in England.2

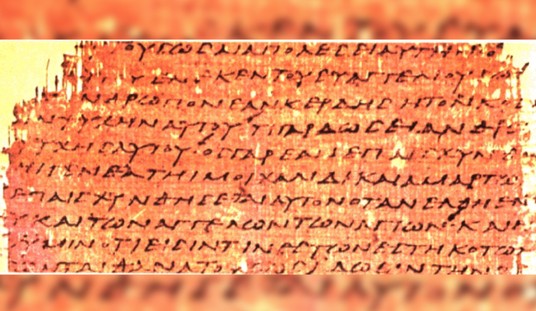

Thus, the Framers adopted two of the three formulations and the phraseology of the English Statute of Treason enacted in 1350,3 but they conspicuously omitted the phrase defining as treason the compass[ing] or imagin[ing] the death of our lord the King,4 under which most of the English law of constructive treason had been developed.5 Beyond limiting Congress’s power to define treason,6 the Clause also limits Congress’s ability to make proof of the offense of treason easy to establish7 and to define the punishment for treason.8

The thing that has me petting this peeve is this: The elements of treason in the United States are:

- Levying War: The first element is "levying War against [the United States]." This means engaging in an actual rebellion or insurrection against the government of the United States.

Pay close attention here. It's got to be actually levying war. Real live shooting and stuff. And it's a good thing because the Biden administration would have hung all the J6 "insurrectionists" before Trump could have pardoned them. A posthumous pardon isn't much comfort. - Adhering to Enemies, Giving Them Aid and Comfort: The second element involves:

- Adhering to the enemies of the United States, which implies allegiance or attachment to these enemies.

- Giving them Aid and Comfort, which includes actions that support or benefit the enemy, directly or indirectly.

Again, pay attention. It's treasonous to "adhere to the enemies of the United States" and "give them aid and comfort" only if there are actual shooting war hostilities going on.

Now, you might think that "enemies" is the out here — after all, aren't China, Russia, and Iran "enemies"?

And the answer is, well, no. Grok summarizes this:

Thus, an "enemy of the United States" in the context of treason involves entities with whom the U.S. is in active, recognized military conflict, whether through declaration or through clear, ongoing hostilities. This definition is narrow to prevent misuse of the treason charge against political dissent or other non-military opposition.

Look, I understand the impulse — it's a common one on the left or the right: accuse your enemies of something heinous, like treason, because they are, like, bad people. Really, really bad people, and they deserve it.

Robert Bolt answered that by putting words into Thomas More's mouth:

William Roper: “So, now you give the Devil the benefit of law!”

Sir Thomas More: “Yes! What would you do? Cut a great road through the law to get after the Devil?”

William Roper: “Yes, I’d cut down every law in England to do that!”

Sir Thomas More: “Oh? And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned ’round on you, where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat? This country is planted thick with laws, from coast to coast, Man’s laws, not God’s! And if you cut them down, and you’re just the man to do it, do you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes, I’d give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety’s sake!”

Sir Thomas More saw the consequences of tearing down the law to get an enemy. Don't imagine that the Founders weren't aware.