A lone wanderer with hard-won fighting skills drifts into a town. There he finds two factions vying for power and devises a way to play one off of the other while keeping his own skin intact through his wits and his otherworldly prowess with weapons, but few words. Lots of stares and squints, more than a few bullets flying, but very few words.

If that simple plot sounds familiar it’s because it powers three titanic tentpoles in pop culture spanning the last 60 years, right up to the present, and launched one of the most iconic careers in film. It first turned up in Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961). Sergio Leone melted it down from Kurosawa and turned the lone samurai into The Man With No Name, who is neither a vintage cowboy nor a classic Western lawman, played by a young TV star named Clint Eastwood.

A Fistful of Dollars (1964) should not have worked, not with that budget (about $200,000), not with a TV actor Hollywood didn’t want (Eastwood), and not by moving the Western epic popularized by the likes of Roy Rogers and John Wayne out of the United States. The film was moved to Italy and Spain for production, where local crews argued over who was paying for what and local actors played townspeople and villains without speaking a word of English. The two actors American audiences would have most recognized, young Eastwood and veteran actor Lee Van Cleef, spoke perhaps the fewest lines of any major movie duo. To top all of that off, Ennio Morricone came up with a spare, flickery, twangy theme that resembled very little of the music that had powered the Western genre to date. It sounded more medieval Japanese with Spanish and Italian notes than any of the grand, sweeping epic themes John Ford or John Wayne used.

The third major pop-culture engine powered by the lone wanderer storyline is The Mandalorian, which knowingly takes more than just that story from Kurosawa, Leone, and Eastwood. It borrows sonic notes from Morricone and the spare-speaking hero from Fistful and its sequels, For a Few Dollars More (1965), and the masterpiece of the trio, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966). Mando’s nickname even sounds a bit like Manco, the Man With No Name’s stated name in For a Few Dollars More. The Man With No Name actually had three names: Joe (Fistful), Manco (More), and Blondie (Ugly). The latter name makes no sense, given the fact that Eastwood has brown hair.

Related: The Mandalorian Is on Track to Be the Best Star Wars in Ages

As noted, none of this should work. There’s no movie magic formula that says it will. Eastwood wasn’t proven bankable talent. The budget for the films was so small he brought his own wardrobe from the TV show that he had been playing on, Rawhide. That’s where his boots came from. He bought the jeans and the hat. The blanket he wore, he seems to have picked up in Spain. Eastwood had one hat on the set of Fistful, which he bought and brought himself. “If I lost that hat,” he told an interviewer years later, “I was a goner.”

The director lacked a track record and had been fired after just one day on a previous film in 1962. Morricone’s soundtrack is haunting but was also a major risk at the time. Who uses a whistler as a key motif for the soundtrack of a dark, violent Western? And they shot the films in Europe despite the Western being the most iconic American film genre of the time, because European crews and actors were cheaper than their American counterparts. The heroless storylines in the Eastwood/Leone trilogy turned the Western epic on its head. Eastwood didn’t speak Italian, and Leone didn’t speak English. Audiences had numerous reasons to reject the films. They also had big, successful Westerns still fresh in their minds: John Wayne had spent millions shooting his Alamo epic in Texas just a few years earlier. Leone spent a lot less filming all three of his films including the epic Civil War battle scene in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

But sometimes alchemy does produce gold. Fistful was a hit and an instant classic. Eastwood’s understated, grim, squint-eyed performance transformed him into an international star. He could say more with a look, a flick of his hand to his sidearm, and a chomp on his cigar than most actors could say with a page of dialogue. He always seems on edge, thinking, determining the sequence in which he will shoot the opponents he faces. He’s not a hero. If anything, he’s a lone schemer trying to survive, who does happen to do the right thing when he has to. Leone kept the dialogue so spare not because he knew the talent he had in Eastwood or how he would necessarily build a scene in editing, but to cut costs. When he does talk, Eastwood has a way of turning the sometimes silly dialog into deadly serious threats.

Eastwood was probably the only actor who could have made it work, plus he had help from Leone’s use of cuts, angles, and fields of view to depict rising tensions or move the story without anyone saying a single word. And then there was Morricone’s haunting, almost alien score.

The Spaghetti Western trilogy made Eastwood an icon-in-the-making and changed movie-making. The films’ loose plots, tight situations, violent gunfights, lack of archetypal heroic figures, and weather-beaten sets, second actors, and extras made the world Leone built look real and lived-in. Nothing in the Man With No Name trilogy looks fake (though the dubbed dialog does take getting used to). Every board and trail, every saloon and brothel, every gun and every face, looks like it has a deep back story. Other filmmakers would take cues from the mixture Leone conjured up.

Eastwood later said it was the Kurosawa aspect that first drew him to Leone’s production, that and a free trip; he was already a fan of Yojimbo. “This thing will either do really well or it won’t do anything,” Eastwood says of his expectations at the time. “Probably the latter.” He thought it might “bomb out” but he would get a trip to Italy and Spain out of it, so he signed on to star, provide his own wardrobe, and keep track of his own props. “You all can go to Hell,” Eastwood might as well have been saying to Hollywood, “I’m going to go shoot a weird, low-budget Western with an Italian director in Spain.”

Recommended: You Still Can’t Take the Sky From Me: ‘Firefly’ Shines in the Age of Lockdowns

Kurosawa’s towering work on The Hidden Fortress (1958) would influence two Hollywood films that have become monsters in their own right: The Guns of Navarone (1961) and then Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1977), two different war pictures that focus on one side’s need to remove the other side’s biggest weapon. Star Wars: Rogue One returned to that basic plotline decades later and it still works. Harrison Ford starred in Navarone’s 1978 sequel a year after starring in Star Wars IV as space cowboy and smuggler Han Solo, creating his own iconic character.

One of the many reasons Star Wars IV works from the first frame is that George Lucas built a galaxy that looked lived in, with worn ships, dusty towns on backwater planets, and second-fiddle character actors who look like they’ve lived the lives the film says they have even though most of them appear briefly and aren’t human. Lucas owes quite a bit to Leone and Eastwood. Ford might admit he owes some of his other iconic character, Indiana Jones, to Eastwood’s Man With No Name.

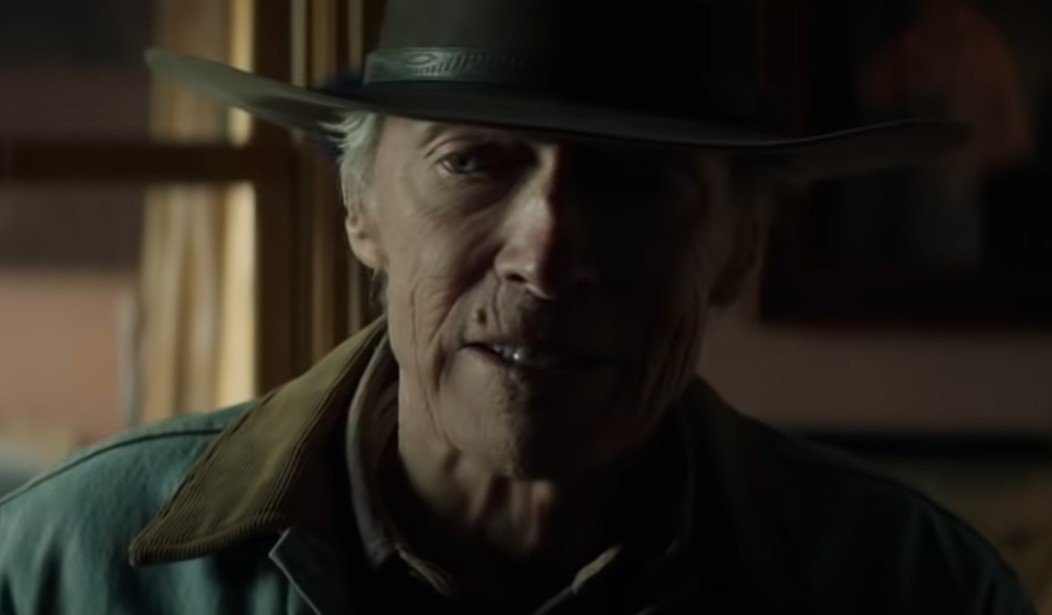

Eastwood carried the facets that made him an icon through the 1970s Dirty Harry films and his return to Westerns with Pale Rider (1985) and Unforgiven (1992) at a time when the Western was beyond dated. Both were hits anyway. The latter especially feels like the Man With No Name has returned for the final judgment of his immortal soul. A year later he played an undisputed hero in In the Line of Fire. Eastwood’s film catalog crosses seven decades now and includes Westerns, comedies, cops, jazz giants, drug smugglers, romance, political thrillers, and just about anything else one can imagine.

He’s back at age 91, having seen and done everything from directing Oscar-winning films to talking to an empty chair in front of the whole world (I was in the room for that performance, by the way, and it worked very well in person). His latest film is Cry Macho, in which he stars and directs. He doesn’t portray the Man With No Name, but his 2021 character might be Manco’s modern grandson.

“I used to be a lot of things,” Eastwood’s Macho character says, “but I’m not now.”

Clint Eastwood has been everything there is to be in film, and it all started when he took the risk to work for an Italian director on a shoestring budget in Spain making a little Western movie in which he said very little while speaking volumes with his squint and his sidearm.

One thing Clint Eastwood is and will always be is a master of film and a gigantic talent — an American legend. It’s good to see him back on the big screen again.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member