If you intend to bust myths, it’s wise to get the details right.

Three Texas writers — two journalists, one a political operative aligned with the Democratic Party — are out with a new book that is making heavy rotation in mainstream media articles. They’re benefiting from some solid promotion and should thank their publisher’s PR arm. It’s doing its job. Their book is being discussed and will likely sell a few copies.

In their quest to make a buck, it’s unfortunate that the writers who say they’re seeking to overturn “myths” about the Alamo are merely fostering new myths about it.

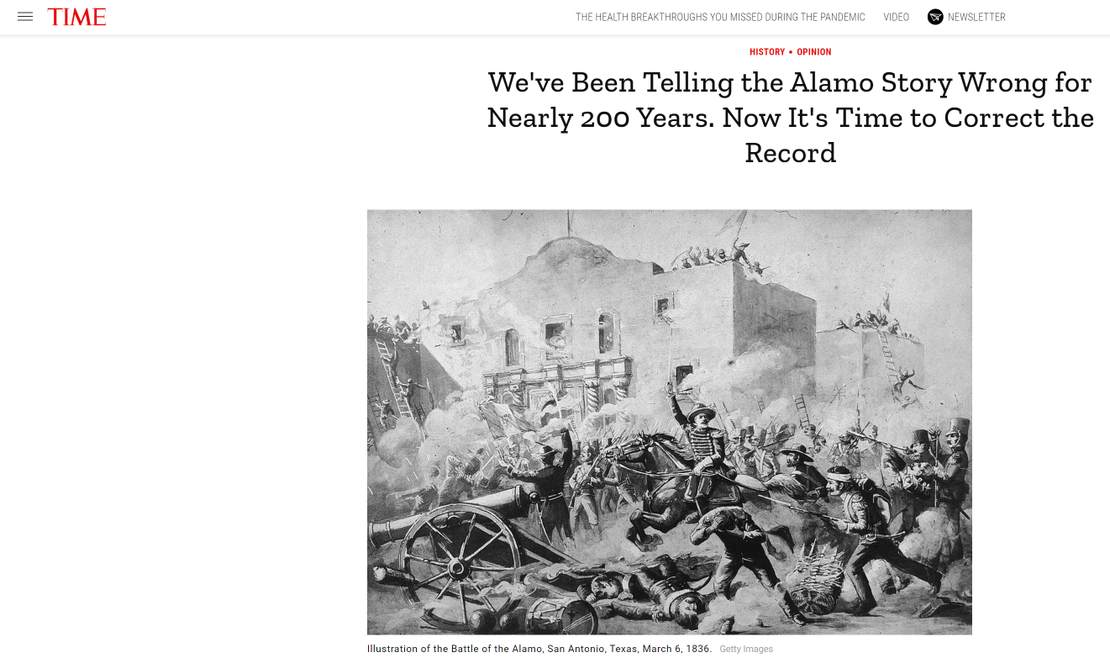

We’ll begin with the mainstream media’s ignorance about the Alamo itself — the structure of the place, as well as the battle. Here’s a screenshot of TIME Magazine’s take, written by two of the three authors of the book.

Alamo and Texas history scholars, or really anyone who knows much about the battle at all, should immediately spot the issues with using this particular illustration to head an article that purports to dismantle Alamo “myths.” One hopes that the three authors of the book did not select this image. The fact that it has accompanied their article in a major publication indicates at least some level of approval for it. It says clearly that TIME has no clue.

Here’s the most glaring problem: The iconic hump in the top middle of the Alamo’s facade was not there in 1836. The front section of the Alamo also had no roof on which those defenders in the top corner of the church, who appear to be waving an American flag while their brethren are being slaughtered right in front of them, can stand. (Not helpful, guys — get down there and fight!) Everything is wrong with that section of the illustration. Why do not the authors consider it problematic misinformation?

The authors slam John Wayne in the piece, calling his 1960 movie a “font of misinformation.” It’s true, the movie didn’t get every detail of the battle exactly correct. It got a lot wrong. Historical investigations and archaeology continue to discover new things about the Alamo, which is wonderful. We know more now than was known about a lot of things in 1960. We also know less in some ways, as time removes us from the heat of one battle and into other battles that take people and circumstances out of relevant context. No movie about a historical event ever does get everything right. To get every detail about the siege and battle of the Alamo correct, it would have to extend to 13 days, for one thing. Even more recent depictions of battles and events that happened in more recent times get this or that detail wrong. It’s Hollywood, not academic studies, as the authors surely know. Oliver Stone managed to make a hero of the crank prosecutor Jim Garrison in JFK, but media ignored that and still do.

John Wayne did manage to get one big and obvious thing about the Alamo church building right. Some years back I went to the Alamo set that Wayne built for the movie, to see it before it closed to the public forever. It’s still standing, out in Bracketville, Texas, west of San Antonio. Here’s a clear shot of what it looked like as of 2017 or so.

No hump. John Wayne 1, current Alamo detractors 0.

That’s because the United States Army was responsible for adding that hump, more than a decade after the Battle of the Alamo. I won’t go into all the details, which are available online and in libraries, but for the curious, Google “Edward Everett Alamo” and start investigating. You’ll learn quite a few interesting details about the Alamo after 1836. For one thing, you’ll learn about that hump we all know today (which Everett himself didn’t like), and you’ll learn that Everett’s unit discovered what he described as “skeletons and relics” left over from the battle. There are no records I know of that detail what his unit did with those items but it’s probable that the bones are buried somewhere on-site and any “relics” went home with the soldiers. These were not unusual practices of the time. The Alamo had been left unkempt after the battle, which does not suggest that its defenders weren’t regarded as heroes (Juan Seguin cleared that up in 1837 — they were seen as heroes at the time and not just by Anglos). It does suggest that Texas was a chaotic place in the years following the revolution, and preservation as such was not yet a value. Survival was more top of mind at that point in history.

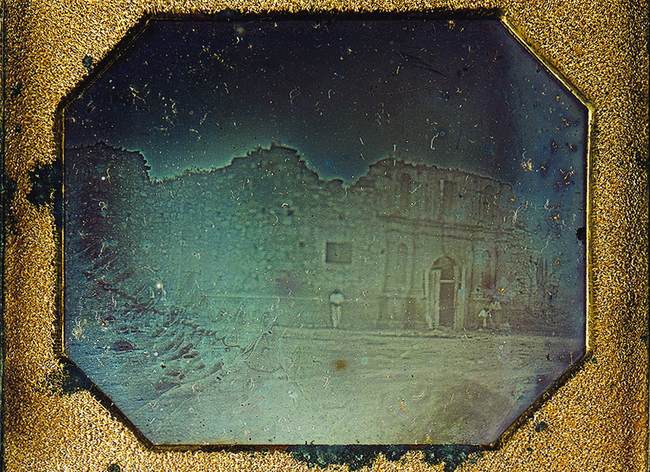

The very first known photo ever taken of Texas was taken at the Alamo. It’s a Daguerreotype. Check out what it shows about the Alamo at the time it was taken, circa 1849. The Briscoe Center at UT Austin holds the original.

Again, no hump. The Army added it during some renovations and clean-up in 1850. So why harp about the hump? What’s the big deal?

Any author who writes anything at all about the Alamo ought to know the hump was not there in 1836. It’s basic to the Alamo’s story.

So is the fact that, of all the sites in all the vast lands of Texas in 1849, the earliest known image taken anywhere in the state was taken at the Alamo. What might this suggest about the battle’s place in the state’s state of mind even in those early years?

The rest of the TIME piece is no better. It questions the defenders’ bravery, which will get tongues wagging but is not fair at all to the men who — unlike the authors or any of us — actually stayed in the compound after Santa Anna surrounded it. It’s also deeply unfair to the Immortal 32, who rode into the Alamo after Travis’ call for reinforcements. They surely knew riding into the Alamo at that point, with it already under siege, meant certain death. But they did it anyway. Whether Travis drew a line in the sand has been debated for years and that debate is not new to anyone who has studied the Alamo to any extent, as is the final fate of David Crockett. Both are discussed by tour guides at the Alamo today if you ask them.

The men stayed when they could have slipped out during the long siege. They knew what was coming. Travis knew when he fired the fort’s largest cannon at Santa Anna’s blood-red flag that he was being defiant, and he and all the men inside knew what Santa Anna would do based on his actions at Zacatecas as well as his open declaration to treat them as pirates. If that’s not bravery, perhaps the term has no meaning in our time.

They question the defenders also because Mexican lancers report that many of them retreated as the fortress fell, and the lancers rode them down and killed them. This does not really change a lot if you know 19th-century warfare. Besieged forces could leave a compound for any of several reasons, including a route (“Run for your lives!”), strategic retreat, or a sally to fight outside the walls. The authors never consider possibilities other than the first, and do not consider the idea that victors tend to write history. They also fail to note that Santa Anna’s own officers were disturbed at the brutality he ordered them to perpetrate at the Alamo, just as he had ordered soldados to perpetrate atrocities at Zacatecas in 1835 and would repeat again at Goliad. The authors do mention Santa Anna’s feelings, though. As if anyone who has taken a look at his character through the lens of multiple actions and decisions of his should concern themselves with the “Napoleon of the West’s” inner dialogue.

I don’t wish to start a flame war with the authors, who have called me “Mr. Alamo.” I rather like the term and intend to use it. I’ve met one of them, and he’s affable and I enjoyed his company despite the gulf between our politics.

I don’t like folks trying to make a buck by beating up the dead, and I don’t appreciate silence from the media in San Antonio or from the public officials who ought to be questioning these authors who bash the Alamo today. One must wonder what their priorities are, just as one ought to question how such glaring errors as those in the illustration TIME chose to accompany its article can find their way to the masthead of what was once one of America’s most prestigious publications.

Update: Vanity Fair used the same anachronistic illustration in its article about the book in question. This tells us a thing or two.

The editorial staffs at these publications don’t know much if anything about the Alamo. The publisher of a book such as this one, in the case of this book the publisher is Penguin, will engage in a public relations push to promote the book. The push for this book has been quite successful; articles about it are everywhere, all of them following the same general arguments about the Alamo, though some have focused on the artifact collection that Phil Collins donated for free to Texas a few years back. Not one publication that has run a piece on the book has questioned it, which again tells us this is a PR push to sell a book, not actual news reporting, even though some of the pieces are written by individuals other than the authors of the book.

The PR push will have been approved at the publisher and very likely by the authors themselves or their agent, who would or should have obtained their approval.

Did the authors who set out to bust Alamo myths know of the issues with the illustration, or not? There’s really no excuse here. If they used the illustration knowing its issues without mentioning those issues to readers, they engaged in misinformation. If they used it unaware of its issues, they know a lot less about the Alamo than they claim.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member