WASHINGTON – An Iran expert said the interim agreement on the country’s nuclear program will bring limited relief to Iran and will not necessarily ease the regime’s existential challenge.

Speaking at a panel of Iran experts at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., Suzanne Maloney, senior fellow for foreign policy at the Brookings Institution, said she was stunned that the Iranians were willing to accept such a “relatively paltry amount” in terms of funds and the facilitation of new business as part of the Geneva agreement.

“The administration is quite correct when they’ve been describing consistently that the package that was offered in Geneva was a modest one,” she said.

Under the proposal offered in Geneva, Iran will be allowed to access $4.2 billion of its own money held in bank accounts outside of Iran over the next six months. Other sanctions will also be lifted to allow Iran to engage in petrochemical exports, imports for its automobile industry, and gold trade for a period of six months.

She said the relief package would prove not to be a “shot in the arm” to the Iranian economy at this point, but, in fact, it might worsen the predicament of the Iranian economy because of the threat of liquidity flowing into the country.

“Liquidity is not the major demand of Iran…the difficulty is with the domestic structure of the economy and with doing business abroad. The fact that Iranians can’t get a letter of credit and they can’t engage in simple trade remains pretty much the case,” Maloney said. “So whatever additional revenues may accrue to the government…and the Revolutionary Guard as a result of these new sanctions is paltry and would do little to affect the overall competitiveness of the economy until certain structural issues can be addressed.”

Maloney said the economic crisis Iran is facing today is “a louder and stronger echo” of economic crises that the Islamic Republic has faced previously throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

During the Iran-Iraq War, the price of oil dropped and the burdens of the war and social spending became too large and too difficult for the Islamic Republic to bear. In 1993-1994, the postwar boom in imports and consumption contributed to a debt crisis that again forced a retrenchment in government spending.

She said on each of these occasions Iran dealt with the crisis through a couple of different mechanisms, such as trying to establish austerity programs and implementing a series of political and social reforms.

“In each of these cases Iran managed to muddle through,” she said. “The difference between today and those periods…is the sanctions.”

Maloney said Iran had sought during the economic crises of the 1980s and 1990s to mitigate some of the effects of domestic economic pressures by seeking more foreign investment in the oil and gas sector.

Signs of this have started to appear in Iran, Maloney noted. Bijan Namdar Zanganeh, Iran’s oil minister, has begun beating the drum about the return of foreign capital to these sectors after the agreement was announced in late November.

Israeli officials have said the sanctions relief package could be worth as much as $40 billion to Tehran. Senior Obama administration officials have provided a more modest estimate, saying the deal would be worth $7 billion at the most.

“The numbers that have been thrown around by some…$20 or 40 billion…are totally illusory,” she said.

Maloney said the idea that any of these relief measures will generate an influx of foreign exchange into Iran is a “political case, not an economic case.”

Sanctions have cost Iran $120 billion in lost revenue since the U.S. and the European Union started imposing strict penalties on energy, shipping, banking, and other Iran-related transactions in 2010, according to the Treasury Department.

Nevertheless, these international sanctions have been only a part of the economic malaise affecting Iran since the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

Hadi Salehi Esfahani, an economics professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said Iran’s economic woes go beyond sanctions.

Esfahani said Iran’s economy is currently going through a period of stagflation – the combination of high inflation and slow economic growth.

This period of stagflation is not a result of international sanctions but rather because of poor policymaking that has caused negative economic growth and high inflation, he said.

Esfahani attributes Iran’s economic circumstances to two causes: politics and “fiscal dominance” – a situation in which the central bank becomes largely irrelevant and monetary policy’s primary aim is to ensure the solvency of the government. He said Iran’s political system is set up in a way that encourages poor governance and poor decision-making, citing former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s populist policies as examples.

After Ahmadinejad came to power in 2005, he promised to bring “oil money to people’s dinner table.” The last two years for which there is available data, 2010 and 2011, show falling poverty and inequality but also worsening economic conditions in Iran.

Ahmadinejad was able to finance his populist policies due to the influence of Iran’s political class over the central bank, Esfahani said.

Inflation has soared for two years and productivity slumped as even tougher sanctions imposed to counter Tehran’s nuclear program have taken their toll. Inflation had fallen to 36 percent by the end of October and the government aims to bring it below 25 percent by the end of March 2014.

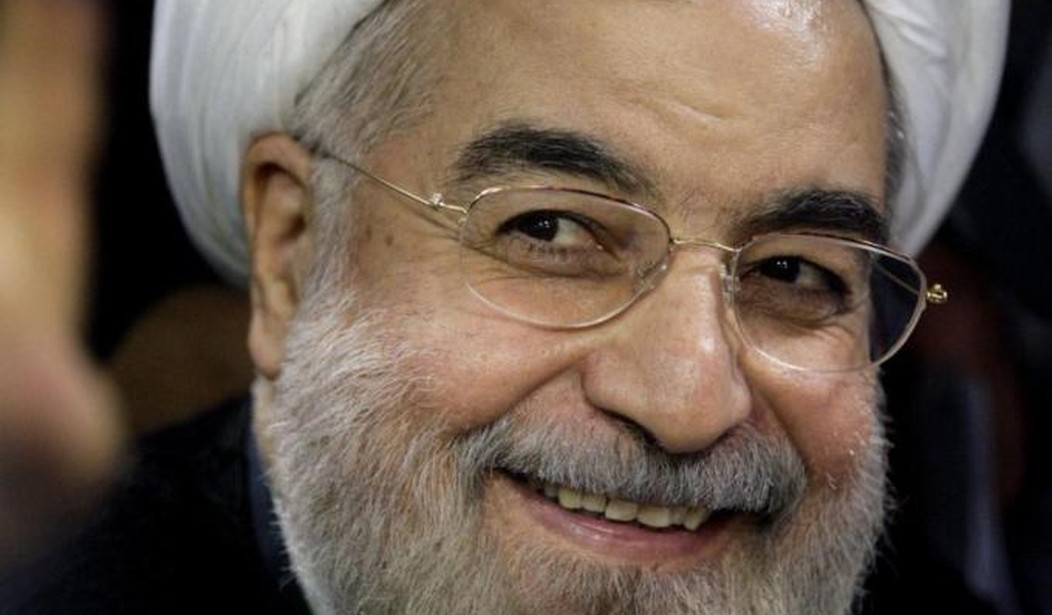

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has vowed to bring down inflation and boost growth to lift the economy. Rouhani himself has admitted that Iran’s economic problems have more to do with the profligacy of his predecessor, openly blaming Ahmadinejad’s mismanagement for the country’s economic problems.

Esfahani said Iran’s leadership has put off pursuing sound economic policies, believing the next group of leaders will tackle the economic issues that beset the country. He noted, however, Rouhani’s attempts to address some of these issues by reforming subsidy programs for the poor and reducing energy subsidies to bring costs closer to market prices.

The International Monetary Fund estimates that Iran’s economy will shrink 1.5 percent this year in inflation-adjusted terms, after an estimated contraction of 1.9 percent in 2012, which was the biggest since the Iran-Iraq War ended in 1988.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member