Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.

—Leo Tolstoy

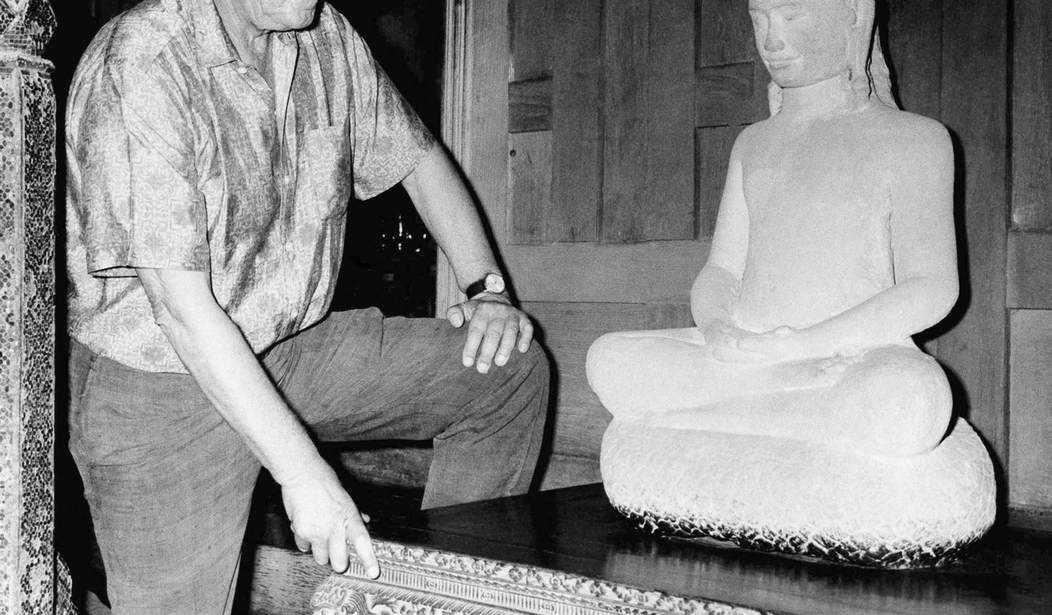

About two weeks ago, at the welcome center in an obscure Thai temple, a white man named River handed me a standard-issue white uniform and a mattress flimsy enough to fold and carry before showing me to my 6 x 8 quarters.

No air conditioning — which is damn near a violation of the Geneva Convention in Southeast Asia.

I hadn’t arrived at prison, although it felt like prison in certain respects.

Strict rules regulated behavior. Spartan meals were taken communally in a large chow hall. Creature comforts were minimal.

“Are you from Canada?” I asked River in one of the very few conversations I had there. I thought I had detected an accent. It could just as well have been a Minnesotan one, though.

“No, they wouldn’t even let me in,” he answered, without elaborating.

I was assured, then, that I had been vindicated in my assumption, based on his mannerisms and drawing from my well of past experiences working with ex-cons in various jobs, that he had, in fact, done some hard time.

Former inmates, in my experience, have a lot of affectations that betray their past, in many of the same ways that former military men do. They exude a sternness and lack of frills in how they walk and move; flamboyance makes one a target of peers or superiors. A lot have that thousand-yard stare of a man who has seen some things not easily discarded.

The institutions they had partaken in had, in short, shaped them irrevocably.

Related: Democrat Hypocrites Accuse Trump of Plotting to Throw Political Enemies in ‘Internment Camps’

During seven days of enforced silence, strangers in all-white uniforms moved in and out of my field of vision constantly. I saw these people every day, but most I never heard utter a word — total black boxes.

Vipassana, in its imperfect translation stripped of the cultural context from which it emerged, means “seeing clearly” or some approximation thereof.

The gist is coming to reality through the only means possible, which is a cultivated deep awareness, to escape the prison of the grasping mind and all of the sensory distractions that assail us every waking moment if we don’t pay attention.

The goal of the meditation is to maintain an open awareness of everything going on internally and externally, but not to either grasp for positive feelings/thoughts/emotions or to run from negative ones. When a thought or feeling surfaces, you just note it mentally with a tag (“feeling”/”thinking”/”seeing”/”hearing”) and return to the present. The distractions can never be fully eliminated, but the goal is to diminish their ability to hijack the mind.

The regimented schedule went like this:

Wake up at 4 a.m.; meditate for thirty minutes; take a twenty-minute break; eat breakfast; meditate; break; lunch; meditate; break; meditate; break; meditate; break… sleep at 10 p.m.

That’s all I did all day every day for seven straight days, from 4 a.m. until 10 p.m., all in near-total solitude, as it was made clear that fraternizing with the other meditators was verboten.

Nowhere to run from the present moment, staring you down.

One would not chase after the past,

Nor place expectations on the future.

What is past is left behind.

The future is as yet unreached.

Whatever quality is present

One clearly sees right there,

Unvanquished, unshaken,

That’s how one develops the mind.Ardently doing one’s duty today,

For — who knows? — tomorrow death may come.

There is no bargaining with Death and his mighty horde.Whoever lives thus ardently, relentlessly

Both day and night,

Has truly had an auspicious day:

So says the Peaceful Sage.

—“An Auspicious Day”

In a world where distractions from emotional and physical discomforts are literally at the tip of our fingers, facing each moment head-on often felt like a battle. At times, the experience was overwhelming to the point of questioning my sanity. In fact, on the intake form, one of the questions pertained to any diagnosed mental health conditions, as in, for some people, this kind of regimen can induce psychosis.

Maybe a peaceful embrace of the moment comes easily for some, but for me, it felt like a kind of war.

In the end, though, I felt like the payoff was some kind of insight that defies description, which seems inaccessible when one lets the monkey mind bounce chaotically from sensory input to sensory input.

Via Journal of Scientific Research in Medical Sciences (emphasis added):

Vipassana seeks self transformation through self observation, where the meditator pays disciplined attention to the physical sensations that continuously interact with and condition the mind… to reduce the tendency of the mind to dwell on the past (thereby reducing regrets), or to delve into the future (thus lowering expectations and anxieties), helping the participant to remain in the ‘here and now’ and achieve relative mental tranquillity.

If you’re ever around Chiang Mai, Thailand, and you’re interested, the program oriented around international visitors at Wat Chom Tong is called Northern Vipassana. (“Wat” is the Thai word for “temple.”)

(As a side note, it is worth noting that there is no idolatry in Vipassana meditation or Buddhism at large. The Buddha, rather than any kind of deity, was just a teacher. So, even if you’re a Christian, the practice of Vipassana itself is not incompatible with other religious restrictions.)