So… who had Vermont in the “State Hardest Hit By Irene” pool?

http://youtu.be/WpRErzxj0Uo

Hurricane Irene made landfall in three places Saturday and Sunday: first at Cape Lookout, North Carolina, then near Beach Haven, New Jersey (ten miles north of Atlantic City), and finally at Coney Island, New York. But this storm won’t be remembered for its impact on the coast. Oh, there was wind annd surge, and there was damage: the Outer Banks Highway was destroyed, Hoboken was flooded, and Lower Manhattan’s seawall was overtopped, among other effects. But when the best an AP reporter can do for a lead quote about a disaster is, “You could see newspaper stands floating down the street,” that’s a pretty good sign it wasn’t exactly the storm of the century — at least not along the coastlines where it hit. Of particular note, flooding in New York was far more shallow and limited than had been feared.

Instead, Irene will be remembered first and foremost for her inland impacts, specifically the catastrophic river flooding now underway in, among other places, the Catskills of New York and, most especially, the last state in the Northeast to make a pre-storm disaster declaration: Vermont.

http://youtu.be/M8zZLyct_D8

(WARNING: Second clip contains profanity.)

The situation in Vermont is pretty terrible, and getting worse as rivers rise. (That appears likely to be the major Irene-related storyline going forward.) Even in New Jersey, where fears of a heavy impact along the shoreline caused Governor Chris Christie to famously advise residents to “Get the Hell off the beach,” the biggest problem was not storm-surge flooding, but river flooding. (“Get the Hell off the riverbank”?)

The inland flooding was no surprise; indeed, I’d been saying for days that it might be “biggest threat of all.” Still, it’s impressive and awful to see the rainfall totals, which are just freaking huge, and the results are devastating in many cases. Irene’s unusually slow movement for this latitude, plus its interaction with a stationary front, have combined to produce a truly historic flooding event that will be the hurricane’s biggest meteorological legacy.

Just as inland flooding was no surprise, the lack of devastating winds was likewise hardly a shocker. We’ve suspected since Wednesday afternoon, and known since Friday morning, that Irene’s winds would not be a huge problem. You can safely ignore the deranged, Drudge-linked conspiracy theory that this 950 millibar storm was somehow a trumped-up tropical depression: plenty of wind observations demonstrate that it was certainly a Category 1 hurricane at landfall in North Carolina, and at least a strong tropical storm in New York and New Jersey. Nevertheless, Irene’s winds were obviously nowhere near what was legitimately feared when it appeared, at midweek last week, that the hurricane might hit North Carolina as a Category 3 or 4, and weaken only to a Category 2 or 3 by its more northern landfalls. But, again, we knew by Friday that the winds would likely underwhelm, and anyone who expected otherwise by Saturday was either not paying attention, being misled by media hype, or both.

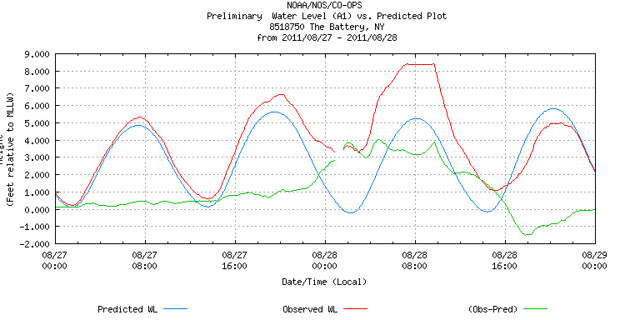

What was a surprise was the storm surge — or relative lack thereof. You’ll remember that, even after it became apparent (and was acknowledged in the forecasts) that Irene would make landfall in a weakened state, forecasters were still expecting a storm surge significantly higher than a “typical” hurricane of Irene’s anticipated wind speed. As Dr. Jeff Masters put it Friday morning, “we can…expect a storm surge one full Saffir-Simpson Category higher than Irene’s winds.” Instead, Irene produced a storm surge topping out at roughly 4 feet all up and down the coast — exactly what you’d expect from a storm on the borderline between Category 1 hurricane (4-5 feet) and a tropical storm (0-3 feet). The only reason New York flooded at all was because Irene came in at almost exactly high tide. The tide alone (slightly elevated due to the New Moon), 5 feet above the low water mark, did more than half the work of overtopping those 8-foot seawalls. And they were only just barely overtopped, which is why you saw reporters standing in ankle-deep waters rather than seeing Lower Manhattan transformed into a latter-day Atlantis.

Why did the storm surge (like so many pieces of economic data recently) underperform expectations? I’m frankly not certain. Remember, I’m not a meteorologist, and I’m certainly not a hydrologist. But I’ve seen this story before, as I pointed out Friday night, when surge fears were high:

But will the surge predictions be borne out? I remember well the predictions of a catastrophic, higher-than-the-winds-would-indicate storm surge with Hurricane Ike in 2008, and those predictions weren’t borne out by the reality (although the surge was plenty bad). Will the same thing happen with Irene, or will the surge meet (or exceed) forecasters’ expectations? I just don’t know.

Ike and Irene were both unusually large storms with unusually deep pressures, whose winds didn’t strengthen as much as expected before landfall, and both resulted in unmet expectations of terrible storm surge. I’m not qualified to opine on what exactly went wrong with these predictions — though if the late Alan Sullivan were still with us, perhaps he’d revive his pimple/hive analogy — nor to suggest changes to the models or anything like that. But it’s certainly worth noting that the last two hurricanes to make landfall in the United States were both huge storms that were expected to cause storm surges well in excess of their wind strength, and both failed to meet the expectations of the computer models. Hopefully the NHC’s post-season analysis of Irene will have some answers on this. Or maybe there’s a Ph.D. thesis in this question for some enterprising meteorology student.

Of course, the big question most people are asking about Irene isn’t why its storm surge was 4 feet instead of 6 or 8, but why it was only a minimal hurricane / strong tropical storm at landfall in the first place. It’s tough for me to get too exercised about that question, since that particular die was cast long ago, between Wednesday afternoon and Friday morning. But anyway, the New York Times does a pretty good job explaining it:

“We were expecting a stronger storm to come into North Carolina,” said James Franklin, chief of the hurricane specialist unit at the National Hurricane Center in Miami. “We had every reason to believe it would strengthen after the Bahamas.”

He added, “What we got wrong was the structure of the storm.”

Forecasters had expected that a spinning band of clouds near its center, called the inner eyewall, would collapse and be replaced by an outer band that would then slowly contract. Such “eyewall replacement cycles” have been known to cause hurricanes to strengthen.

While its eyewall did collapse, Irene never completed the cycle, Mr. Franklin said. “There were a lot of rain bands competing for the same energy,” he said. “So when the eyewall collapsed, there were winds over a large area.”

That led the storm to be much larger, but with the winds spread over a larger area, they were less intense.

All of which brings us to the inevitable questions about “hype.” Was Irene overhyped? Well, yes and no. The fearful possibility of a monster hurricane hitting North Carolina, then taking an exceedingly dangerous and potentially mega-destructive track up the densely populated East Coast, was very real and fully justified as of midweek. And indeed, Irene took precisely the near-worst-case track that was being discussed, with near-worst-case tidal timing for both Chesapeake Bay and New York harbor to boot. That’s 2 out of the 3 necessary conditions to produce a mega-disaster. But all 3 must happen for the “worst case” to occur, and Irene only managed to bat .667. Worst-case scenarios generally require a bunch of bad things to happen in just the right (or rather wrong) combination; otherwise, the feared disaster, no matter how real the threat was, doesn’t come to pass. Here, Irene simply failed to ever became a true “monster” in terms of intensity, and thus her effects were vastly less severe than what they could have been. There was nothing preordained or inevitable about that failure — indeed, the meta-conditions were broadly favorable for rapid strengthening — yet it didn’t happen, demonstrating once again forecasters’ admitted lack of skill at predicting hurricane intensity (in stark contrast to the ever increasing skill, sharply on display here, at predicting hurricanes’ tracks up to 72 hours or so).

As I wrote in my post about “misconceptions,” the mere fact that a worst-case scenario doesn’t occur is hardly proof that it should never have been considered a possibility, or that precautions taken against such a scenario were therefore unwarranted. That’s totally illogical. I’m sure NOAA officials and others would love to have access to the 20/20 Hindsight Computer Model that some commentators seem to possess, but absent that, I believe it was completely justified and necessary to evacuate the folks who were evacuated, given the uncertainties in the forecast at the time decisions had to be made (specifically with regard to the storm surge). It’s the nature of the beast, given the current limits of our forecasting ability, that most “alarms” will be “false alarms.” It’s simply impossible to know with certainty what a storm will do at the time when evacuation decisions must be made, so we have no choice but to “prepare for the worst,” knowing full well that, in most cases and in most places, the worst will not happen. Thus, the fact of a “false alarm,” without more, is not evidence of improper “hype.”

Yet overhype certainly exists, not so much in the forecasts or the precautions, but in the media coverage. “Preparation for the worst-case scenario makes sense,” writes the Telegraph‘s Toby Harnden, “and could have saved hundreds during Katrina. But the worst-case scenario was largely portrayed as inevitable.” That’s a big problem in the early stages of hurricane coverage: the tendency to filter out the uncertainties, and treat the worst-case possibilities as probabilities or near-certainties. This, in turn, feeds into a cycle of self-perpetuating hype, which at some point seems to pass a “point of no return,” after which any walk-back of the doomsday talk is seen as irresponsibly advising people to “let their guard down” — not to mention hurting ratings. That helps cause what I view as the primary problem, which I’ve observed many times over the years: the MSM’s failure to adjust the tone and substance of the coverage once it has become apparent that the worst-case scenario(s), despite having previously been realistic possibilities, have now become unrealistic. In other words, they fail to dial down the hype a notch when the hype, once reasonable, is clearly no longer justified. I tweeted Friday morning about this, stating: “Media must be careful today. Fine line b/w preventing complacency & overhyping a weakened Irene (which breeds cynicism and…complacency). Ideally, you communicate that Irene is a big deal that people should take seriously, but no longer likely to be an apocalyptic hellstorm. But that’s hard to do in practice, especially when MSM weather coverage generally has two settings: 1. #Ignore. 2. #OMGApocalypticHellstorm!”

As I wrote Saturday morning, “we can now be quite confident this won’t be a world-historical disaster… even while being equally confident that it is a force to be reckoned with, and one residents should not blow off. Surely there must be some way to communicate both of these concepts simultaneously.” Needless to say, this properly calibrated, nuanced message didn’t win the day. Instead, many folks apparently continued to believe they were indeed dealing with an apocalyptic hellstorm, a world-historic disaster of the sort that had been, in reality, pretty much off the table since Thursday or Friday. Why did they believe this? Because many folks in the media didn’t convey otherwise, even though the National Hurricane Center had made the diminished threat clear. (It’s not like I was going out on a limb. I was just relaying the publicly available forecast information.)

This pattern is dangerous, because it can breed both complacency and arrogance — the latter exemplified by Anne Thompson’s comment on the NBC Nightly News that New Yorkers had gained their “swagger” back because “New York took the best that Irene could give, and made it through.” That statement might make sense, if Irene had given New York anything close to “the best [it] could give.” But Irene didn’t do that. It’s absolutely critical to understand that this was nowhere near the worst-case scenario for NYC & environs, thanks to Irene’s limited strength. That scenario will occur come to pass someday; it just wasn’t today, thank goodness. But my fear now is that, when the eventual day of reckoning comes, folks won’t take it seriously because “they said that about Irene too.” Complacency caused by media overhype can kill, just as surely as complacency caused by people “letting their guard down” due to underhype. Finding the proper balance is very tricky, and impossible to do perfectly — but the media certainly needs to do better.

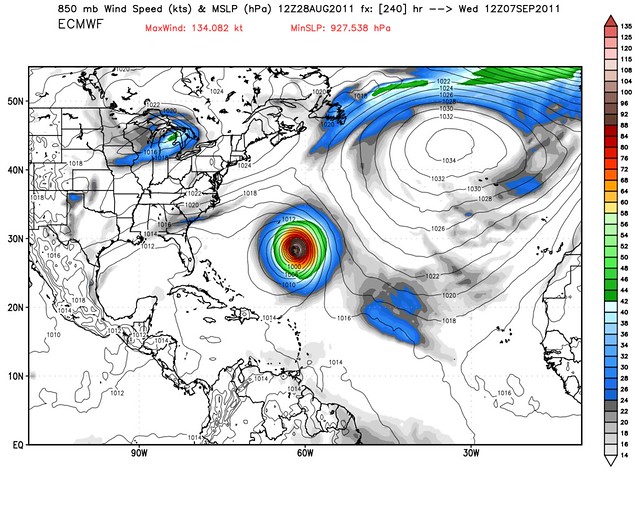

Heck, maybe the “day of reckoning” will come sooner rather than later. Let’s hope not. But computer models are calling for “Invest 92L,” a tropical wave off Africa, to eventually become Hurricane Katia (the replacement on the six-year rotating name list for the retired name “Katrina”), and some models think it will eventually menace the East Coast in about two weeks’ time, potentially around the weekend of 9/11. (FSU meteorologist Ryan Maue, he of the beautiful computer model graphics, referred to a Saturday-night model run as the “oh s**t, not again” forecast.) Other models think it will slide harmlessly out to sea. Here’s what the European model predicts for September 7:

It’s way, way, way, WAY too early to tell what “proto-Katia” will do, or to worry about this hypothetical storm. But it just goes to show how active the tropics are right now.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member