For years now, Disney has taken great care of its classic films. The company pulls beloved videos in and out of the “Disney Vault,” both as a clever marketing strategy and as a way to share the best of the best (along with the occasional Eisner-era cheapquel) with new generations of enthusiasts. The advent of new technology — from DVD to Blu-Ray to whatever a Platinum Edition is — means that the classics will remain in fans’ collections for years to come.

That is, except for one film. Believe it or not, one Disney classic has not seen the light of day since 1986. The company has kept it under wraps for over a quarter-century in spite of two Oscars and a revolutionary blend of live action and animation — not to mention the fact that the film inspired a popular attraction that appears in three Disney theme parks. To this day, collectors scramble for bootleg copies — my brother owns two DVDs along with a VHS copy with Japanese subtitles — and at the shareholders’ meeting every year, someone inevitably asks CEO Bob Iger when the movie will finally make its way out of the Disney Vault.

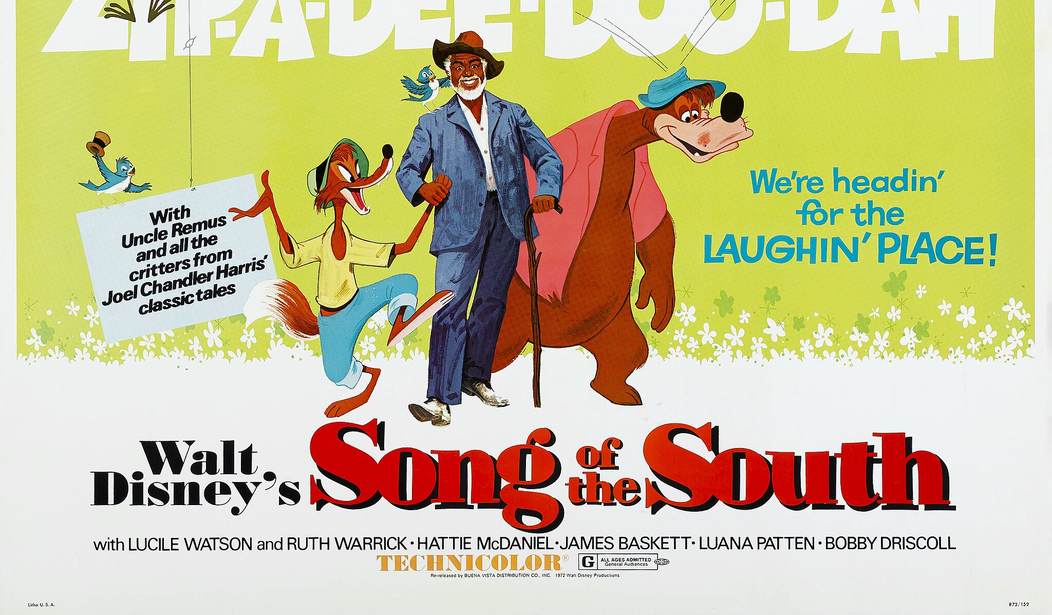

The film? Song of the South. For years critics have derided the picture as an example of the racism of the first half of the 20th century, while fans of the Uncle Remus tales have long pleaded for Disney to rerelease this beloved classic.

The great Leonard Maltin has gone on record advocating Song of the South‘s release as recently as December 2012, in an article which:

…discusses the Walt Disney Treasures series. On these DVDs, Maltin himself introduces the cartoons which might now be considered “politically incorrect,” explaining how times have since changed. The article mentions possibly using this same approach for Song of the South:

-

“I very much hope that the folks at Disney will release ‘Song of the South’ sometime soon,” Maltin said, “and use this same approach — to be responsible in explaining the times it depicts and the attitudes of the period in which it was made.”

Writer Jim Korkis, who began his career as a teenager interviewing legendary Disney animators, chronicles the history of this provocative classic in his newest book Who’s Afraid of the Song of the South? And Other Forbidden Disney Stories (available for Kindle as well). Korkis tells how Walt Disney struggled to make a motion picture he was passionate about, and he writes of the ensuing controversy, which has gone on for over 65 years.

In the book’s foreword, Disney Legend Floyd “Mr. Fun” Norman, the company’s first African-American animator and a fine storyteller in his own right, recalls showing Song of the South at a black church in Los Angeles in the ’80s:

The screening of the Disney film proved insightful. the completely African-American audience absolutely loved the movie and even requested a second screening.

[…]

Yet even today the film continues to be mired on controversy, and that’s a shame. I often remind people that the Disney movie is not a documentary on the American South.

Korkis’ book documents how Song of the South found itself mired in controversy from the start. Walt Disney long admired the folk wisdom and clever stories of Joel Chandler Harris’ tales, and he saw an adaptation of the Uncle Remus canon as an opportunity to right the studio’s ship after the financially difficult war years, as well as a chance to innovate by blending live action and animation.

In an era of Southern segregation and the already churning waters of race relations, Disney took pains to craft the film as carefully as he could. When a first draft by Louisiana writer Dalton Reymond proved so racist as to be beyond the pale, Walt turned to author Maurice Rapf, a communist-leaning (gasp!) Yankee (double gasp!) — who would later find himself blacklisted — to fix the script, and other writers helped whip an acceptable screenplay into shape. The filmmakers chose to set the film after the Civil War, though they were not always clear about the setting. For example, the screenplay presents a greater level of interaction between blacks and whites than during the antebellum era, and Uncle Remus threatens to leave the farmstead of his own accord, whereas he would have had to escape had he still been a slave.

While some black actors turned down roles they deemed too undignified, others relished the chance to work with Disney. Character actor James Baskett threw his all into playing Uncle Remus (along with providing the voices of some animated characters), and the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar for his charming performance (thanks in part to the lobbying efforts of Walt Disney, gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, and Academy president Jean Hersholt). Hattie McDaniel — herself the first African-American Oscar winner — remarked that she would not have chosen to appear in the film if she had thought it “degrading or harmful to [her] people.”

The book does not simply chronicle the film’s controversy. Korkis also manages to tell the compelling story of the making of a motion picture that was ahead of its time in its blending of live action and animation. The author writes of the struggle to seamlessly blend the movie’s two distinct elements, and he chronicles the songwriting and composing process which produced the film’s other Oscar — for the unforgettable tune “Zip-A-Dee-Do-Dah.”

The portion of the book dedicated to Song of the South culminates in the picture’s premiere at Atlanta’s iconic Fox Theatre, where, sadly, the African-American stars could not attend because of the venue’s policy of segregation. Korkis then examines the modern controversy surrounding the movie, as it remains buried in the studio archives, a victim of its own touchy subject matter. Korkis looks at the legacy of Song of the South as it exists today, including the museums dedicated to Joel Chandler Harris in Atlanta and Eatonton, Georgia, and the Disney Parks attraction Splash Mountain — which employs the film’s animated characters (with dialect intact) and memorable songs.

Apparently, Korkis did not feel he had enough material for the story of Song of the South to stand on its own, so he added a section of various “forbidden” stories from the studio’s history. These tales include a glimpse into Walt’s political leanings and the reasons why J. Edgar Hoover kept a file on Disney, the history of Disney’s secret commercial studio, the legend of the “Disneyland Orgy” poster, and the bizarre saga of some of the studio’s educational films (including this unintentionally hilarious gem about what was then called “venereal disease”):

Regardless of which side of the Song of the South controversy you find yourself on, you’ll find a wealth of information and enjoyment in Jim Korkis’ book. While the second half with its assorted stories comes off as a bit uneven, the first portion of Who’s Afraid of the Song of the South weaves a fascinating and completely true tale of an often forgotten Disney classic. Perhaps one day we’ll see a thoughtful documentary account of the film’s controversy as an extra on a Platinum Edition Blu-Ray of Song of the South. Disney fans can dream, can’t they?

Join the conversation as a VIP Member