As veteran Hollywood producer Lynda Obst makes abundantly clear in her enjoyable new book Sleepless in Hollywood: Tales from the New Abnormal in the Movie Business, Hollywood’s got a fevaaaah, and the only prescription is cranking out more and more superhero and sci-fi franchises. Warner Brothers has Batman and Superman, Paramount has the Star Trek and Mission: Impossible franchises, and Disney has Marvel Comics and now Star Wars as well.

Beginning with the subhead of her book’s title, Obst calls this “The New Abnormal” — the Old Abnormal she defines as the revolution that Spielberg and Lucas ushered into Hollywood via Jaws and Star Wars, and basically exhausted itself sometime after 9/11. (Obst explored some of the reasons why in the excerpt of her book in Salon, which we blogged about a couple of weeks ago.) Of course, the Old Abnormal itself replaced an earlier abnormal cinematic era — “New Hollywood.” That was the post-studio system period, when Hollywood stopped ingratiating itself with the audience, and started producing all those dark cynical (and occasionally brilliant) films that dominated the pre-Lucas 1970s, an era whose alpha and omega works were summed up in the title of Peter Biskind’s definitive history of New Hollywood, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls.

Obst explains the formula for ‘The New Abnormal” thusly:

1. You must have heard of the Title before; it must have preawareness.

2. It must sell overseas.

3. It should generate a Franchise and/ or Sequel (also a factor of 1 and 2).

And when you’ve got franchises and sequels, you have much less need for expensive, temperamental superstars. Which explains this recent headline in the London Independent: “The last action heroes: Have Tom Cruise, Will Smith and Brad Pitt lost their mojo?”

Studios now have more control over their product when stars are not involved. This is especially true of superhero movies. The exception that proves the rule came recently when Robert Downey Jr caused a ripple by threatening to stop playing Iron Man. The studio dithered, no doubt knowing they could save a fortune by letting him go. Fans balked and the studio relented. A hefty payday will see him star in Avengers 2 and 3, a comic-book ensemble that doesn’t need Downey Jr in it to guarantee bums on seats.

A caveat is that the appeal of the stars seems to have not been so diminished in foreign markets, especially nascent territories such as China and Russia. There has been a big shift in Hollywood studios’ attitudes in the last 10 years as the takings from foreign markets have started to dwarf those of domestic audiences. So while After Earth was deemed to have bombed in America, foreign takings a week later softened the crash landing.

The reaction of Cruise and Smith to their box-office numbers suggest they are in consolidation mode. Cruise has abandoned plans to star in an adaptation of 60s TV show The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and announced that he’s making a 5th instalment of Mission: Impossible. There’s also talk that he’s considering turning Jerry Maguire into a TV show. Will Smith has been on American talk shows downplaying the weak opening of After Earth and, while talking about looking for more risks in his choices and moving away from blockbusters, he has also been rumoured to be preparing for sequels of Bad Boys, I, Robot and Hancock. Although his Men in Black franchise has seen each sequel make less money than predecessors. The stars are following the studios in relying on their best-known characters to sell their movies.

What’s intriguing is that there seem to be no successors to Cruise, Pitt and Smith. The recent huge blockbuster franchises have been superhero movies, Batman and Spider-Man, or ensembles based on books, Harry Potter, Twilight and Lord of the Rings. It’s hard to imagine Christian Bale breaking box-office records outside of the bat-suit. The summer blockbusters have evolved away from being star vehicles as studios have hit on a formula where they can call the shots. That’s bad news for the non-tights-wearing action star.

It’s actually not all that “intriguing” as to why there are few successors to Cruise, Pitt, Smith, and their older partners-in-greasepaint such Bruce, Sly, Harrison and Schwarzenegger (and Mel Gibson before he nuked his career). They’re the last remaining action-oriented superstars before the rise of World Wide Web completely demassified pop culture beginning in the mid-1990s. Since none of these actors are getting any younger, Hollywood has increasingly relied upon the sci-fi and superhero franchises that existed before the demassification of media to provide a reason for audiences to go out to the movies.

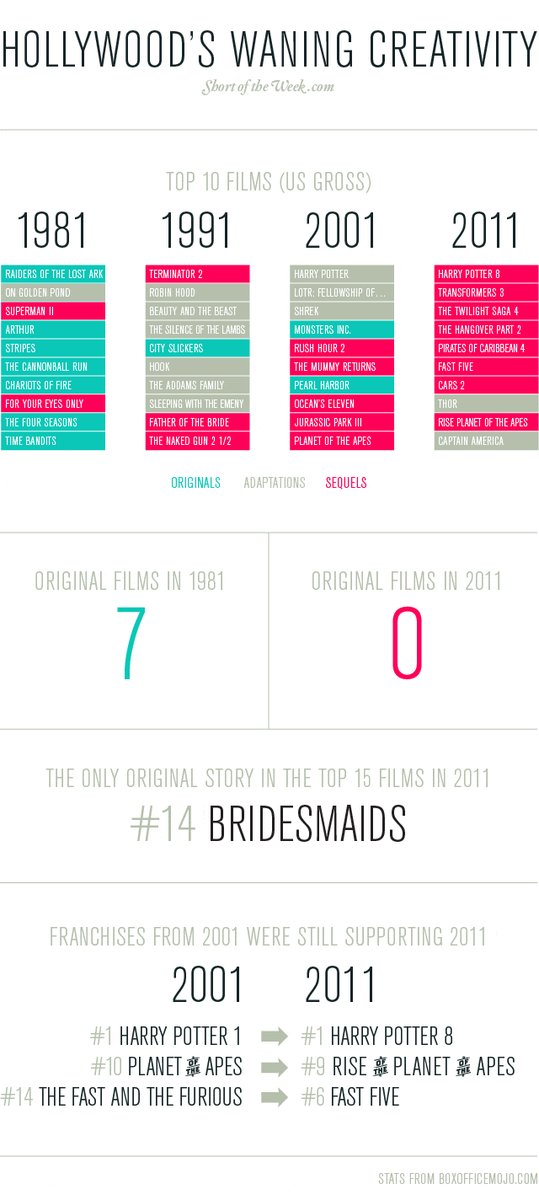

Unfortunately, the result is a dismal chart such as this, reproduced in Sleepless in Hollywood as a damning portrait of Hollywood’s lack of creativity:

On the other hand, there is a new hope, to coin a cinematic phrase, which we’ll discuss right after the page break. (Pick up some popcorn in the lobby while clicking over.)

As a byproduct of the New Abnormal, Obst writes that the movie industry has become increasingly bifurcated, between the aforementioned zillion dollar superhero franchise pictures, and comparatively micro-budget films produced for the indie circuit and cable TV’s growing number of movie channels. (And increasingly, the Web.) The same digital technology that on a mammoth scale powers today’s superhero and sci-fi franchises is also making indie films increasingly affordable, Obst notes. Shooting digitally doesn’t require the expense of buying film stock, which allows for unlimited retakes of scenes. Digital allows a multitude of effects to be added in post-production, and errors airbrushed out. Editing can now be done much more quickly and easily on a computer than grinding on a Moviola. This is already having a dramatic impact on the industry, Obst writes:

With the onset of HD drastically reducing the costs of making independent movies, they can be made on a recently issued credit card, or long-saved Bar Mitzvah money, or by hustling friends or parents. This situation drastically diminishes the power of the “gatekeepers,” creates enormous opportunities for new distributors and opens the door to young talent via YouTube and other Internet outlets. We await filmdom’s Justin Bieber: Just as the savior of the music industry emerged from his home to the world via the Net overnight, our next Scorsese or Fincher is likely to be shooting something unimaginably cool on his or her family’s video camera that will pop up on YouTube and be instantly discovered the same way. It is inevitable.

We now have thousands upon thousands of tiny movies made on microbudgets, financed with personal credit cards. They are all vying to enter film festivals, and the very best of them will end up competing with studio films at Oscar time.

In “Hollywood Goes Bankrupt,” his own take on Obst’s book at Front Page, Ben Shapiro explores what the above passage means for conservatives wishing to break Hollywood’s ideological monopoly:

Everyone in Hollywood is liberal, until it comes time for them to work without pay. Then they’re downright Reaganesque. As less and less pictures get made, and more and more talented people go without work, the pool of labor gets ever larger. That means that actors who used to cost $500,000 per pictures will work for one tenth that. It means that writers with Oscars on their resumes can be had for a song. And it means that the liberal monopoly that controls Hollywood may be crashing down.

There is only one element of Hollywood that prevents this collapse: a monopoly on distribution. The distribution system in Hollywood is still upside-down, with distributors acting as gatekeepers for films. Most of these distributors are liberally-inclined politically, which means that they have no interest in conservative films. They’re profit-drive, sure, but they’re also used to working with a select clique of producers and directors and studios. They aren’t willing to take a risk.

But they can be paid to take a risk. And that’s where conservatives come in. With the means of production becoming ever-cheaper – it’s possible to make a movie that looks like a million bucks for about $100,000 – conservatives don’t have to expend tons of cash to get active in the artistic space. What’s more, they don’t have to build ground up – they can hire the same writers and directors who have been so successful in leveraging liberalism into great films.

Now is a horrible time to be the head of a movie studio. But it’s a great time to be a conservative looking to enter the movie market. All it requires for conservatives to make a serious play for the culture is a level of seriousness about the culture. Rather than sitting on the sidelines condemning the new flicks, it’s important to get involved in making flicks of our own – good movies, rather than politically-driven biopics. The market is shifting. And if conservatives have shown they are good at one thing, it’s taking advantage of market inefficiencies.

Peter Biskind’s 1997 book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls and accompanying documentary explored how the leftists who dominated Hollywood in the 1970s were able to crash the conservative studio system that preceded them. I doubt very much it was her intention, but in Sleepless in Hollywood, Lynda Obst has provided a roadmap for today’s conservatives to find their way in as well.

Who will break down the barriers first?

Update: “Mark my words,” Aaron Clarey writes, linking to our post above, on his Captain Capitalism blog, unlike today, where Ivy League students earn an MBA in “Film Studies” while going deeply into debt — “in the future the TRUE masterpieces and blockbusters will come from people who did NOT study the arts, but rather studied life and lived it.”

Which sounds very much like the people who originally built Hollywood out of sheer trial and error and experimentation — and equally importantly, their sheer love of storytelling on the big screen, and as a result, made far better movies than their much more credentialed but not educated successors.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member