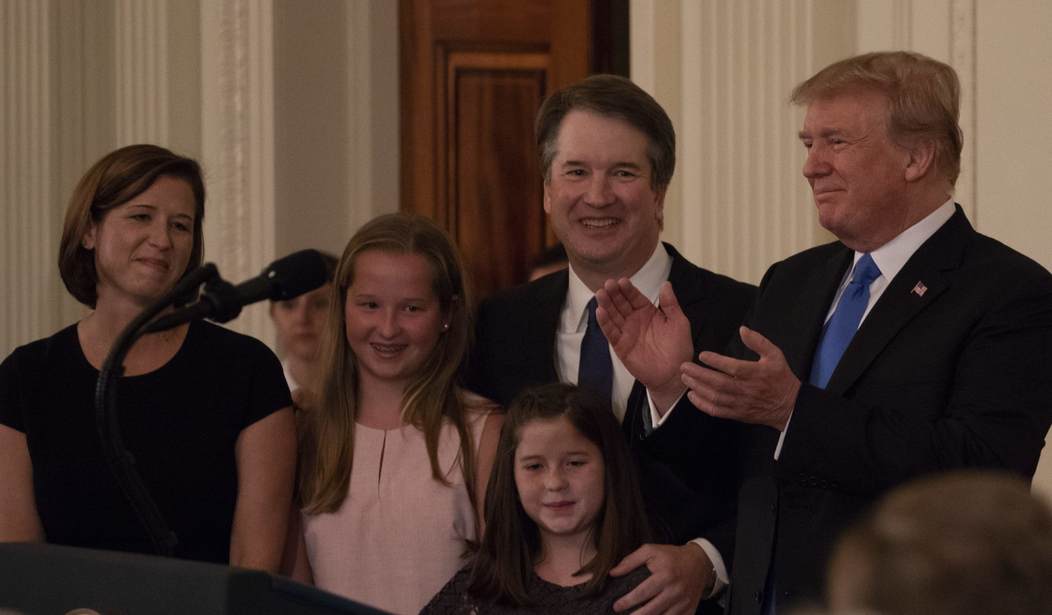

As President Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh faces a confirmation battle in the Senate, conservatives have mostly praised his credentials as an originalist in the mode of Justices Antonin Scalia and Neil Gorsuch. Some have questioned Kavanaugh’s record, however, with the most serious accusations leveled against his ruling in a key Obamacare case. Since Obamacare was the key issue propelling Republicans in 2010 forward, this is a vital issue.

A few months before Chief Justice John Roberts upheld Obamacare’s individual mandate as a tax in the case NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), Kavanaugh wrote an important dissent in a similar case upholding the mandate, Seven-Sky v. Holder (2011). In Seven-Sky, Kavanaugh suggested that the individual mandate could be upheld as a tax, with a small change in the law. Obama’s Solicitor General Donald Verrilli cited Kavanaugh in his arguments for the mandate, and Roberts agreed with Verrilli.

Some conservatives and libertarians have attacked Kavanaugh for giving an “assist” to Verrilli and enabling Roberts to uphold the mandate.

“The role of an umpire is to call balls and strikes — not to coach the pitcher on how to hit the strike zone, or the batter on how to work the next umpire,” Michael F. Cannon, director of health policy studies at the Cato Institute, told PJ Media in an email statement.

Cannon laid out the case against Kavanaugh, and it is complicated, so bear with me.

When Congress passed Obamacare in 2010, the bill included an individual mandate, a provision that forces people who can afford a basic level of health insurance to buy it or else pay a penalty to the IRS. It was unprecedented for Congress to order Americans to purchase a good, so the mandate was always questionable. Congress justified it under the Constitution’s Commerce Clause, which says Congress can regulate interstate commerce.

In Seven-Sky v. Holder, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia upheld the constitutionality of the individual mandate under the Commerce Clause, but Kavanaugh disagreed. Kavanaugh argued that, under the 1876 Anti-Injunction Act (AIA), the court could not even examine the issue.

According to the AIA, if a citizen wants to challenge a tax he or she must have already paid that tax. Then, the citizen could sue the government and request a refund. Since the individual mandate would not come into effect until 2014, no penalty had been paid.

Even though the mandate was not a tax, Kavanaugh argued that it should be treated like a tax for purposes of the AIA, and therefore the court could not even hear the case.

While “Kavanaugh declared the mandate-penalty is a tax only for the purposes of the Anti-Injunction Act, he didn’t stop there,” Cannon told PJ Media. “Since Kavanaugh held that the court did not have jurisdiction to hear the individual-mandate challenge, there was no need for him to weigh in on the merits of that challenge. He could have stopped at the AIA. But he didn’t.”

Instead, Kavanaugh’s dissent went on for pages and pages, and he addressed all sorts of legal issues in the case. Cannon pointed out that “Kavanaugh offered lots of ‘options’ that ‘would ensure that this provision operates as a traditional regulatory tax and readily satisfies the Taxing Clause.’ Beyond just discussing the constitutional issues, why did he offer multiple ways a conservative judge might uphold the mandate when there was no need for him to weigh in on the constitutional issues at all?”

Finally, and most damningly, “Kavanaugh’s discussion of those issues did provide something of a roadmap to the Obama administration and John Roberts,” Cannon argued. In his book “Unprecedented: The Constitutional Challenge to Obamacare,” law professor Josh Blackman argued that Kavanaugh gave Verrilli an “assist” to help Verrilli argue for the constitutionality of Obamacare’s individual mandate.

But did Kavanaugh really give Verrilli an “assist,” or did Verrilli twist Kavanaugh’s words?

The issue is important, because Roberts bought Verrilli’s argument that Obamacare’s mandate could be justified as a tax. He ruled this in spite of key facts: that the final version of Obamacare was drafted in the Senate (and all tax bills must start in the House); that Obamacare explicitly stated the mandate was not a tax; and that Obamacare would not have been able to pass the Senate if Democrat senators thought they were voting for a tax in the individual mandate.

Roberts redefining the mandate as a tax was one of the most egregious high-profile betrayals of originalism in recent history, so if Kavanaugh was indeed complicit, that’s a serious mark against him.

But let’s take a look at what Kavanaugh actually said.

“What I am saying is that the only potential Taxing Clause shortcoming in the current individual mandate provision appears to be relatively slight,” the judge wrote. “And just a minor tweak to the current statutory language would definitively establish the law’s constitutionality under the Taxing Clause (and thereby moot any need to consider the Commerce Clause).”

He did indeed go on to describe “options” that “would ensure that this provision operates as a traditional regulatory tax and readily satisfies the Taxing Clause.”

Kavanaugh said that “a minor tweak” would make the mandate constitutional, but Obamacare was not passed with that minor tweak. While the mandate could be changed to be constitutional as a tax, it would have to be altered for this to happen.

Indeed, Kavanaugh’s dissent in Seven-Sky went on to argue vociferously against the idea that the Commerce Clause justifies the individual mandate.

“To uphold the Affordable Care Act’s mandatory-purchase requirement under the Commerce Clause, we would have to uphold a law that is unprecedented on the federal level in American history,” he wrote. “Under the Government’s Commerce Clause theory, as it freely acknowledged at oral argument, the Government could impose imprisonment or other criminal punishment on citizens who do not have health insurance. That is a rather jarring prospect.”

The judge admitted that “the Affordable Care Act does not impose such criminal penalties.” But… “if we approve the Affordable Care Act’s mandate under the Commerce Clause, we would necessarily be approving criminal punishment — including imprisonment — for failure to comply not only with this Act but also with future mandatory-purchase requirements.”

Kavanaugh further warned that “there seems no good reason its theory would not ultimately extend as well to mandatory purchases of retirement accounts, housing accounts, college savings accounts, disaster insurance, disability insurance, and life insurance, for example. We should hesitate to unnecessarily decide a case that could usher in a significant expansion of congressional authority with no obvious principled limit.”

The D.C. Court of Appeals acknowledged that upholding the mandate on Commerce Clause grounds means allowing Congress to mandate citizens buy private retirement accounts, private college savings accounts, and other such things. Such a drastic ruling involves “a potentially significant infringement of individual liberty,” and therefore “underscores why I think we should be cautious,” Kavanaugh argued.

It is also true that Kavanaugh urged the court to be “cautious about prematurely or unnecessarily rejecting the Government’s Commerce Clause argument,” because “striking down a federal law as beyond Congress’s Commerce Clause authority is a rare, extraordinary, and momentous act for a federal court.”

“The elected Branches designed this law to help provide all Americans with access to affordable health insurance and quality health care, vital policy objectives,” he added. “This legislation was enacted, moreover, after a high-profile and vigorous national debate. Courts must afford great respect to that legislative effort and should be wary of upending it.”

Chief Justice Roberts adopted this argument, writing that “it is not our job to protect the people from the consequences of their political choices.” This went quite a bit further than Kavanaugh, who merely presented a balance between preserving individual liberty and acknowledging Congress’ will.

Similarly, when Verrilli quoted Kavanaugh’s argument that a small change in the law would make the mandate justifiable as a tax, he ignored the fact that Kavanaugh insisted this would require a change — from Congress.

“The Government’s Taxing Clause argument may have a potential problem because of the statute’s legal mandate (although that potential problem is relatively minor and could be easily fixed by Congress, as described above),” Kavanaugh wrote. Again, justifying the mandate as a tax would require an act of Congress.

Kavanaugh has written many long opinions that attracted the attention of Supreme Court justices and figured into Supreme Court rulings. Critics have argued that his dissent in Seven-Sky was intended to signal to the Supreme Court that it could uphold the mandate as a tax.

That seems rather unlikely, however. Kavanaugh explicitly declared that the mandate was not justifiable as a tax as written. Verrilli twisted his words in order to make that case.

Kavanaugh likely went on to emphasize his argument against the mandate’s constitutionality on Commerce Clause grounds. The Supreme Court did indeed accept this argument, striking the mandate down for those reasons. Roberts, however, hesitating to strike down Obamacare against Congress’ will, bent over backwards to justify the mandate as a tax.

In doing so, Roberts was not following Kavanaugh. In an interview with PJ Media, Case Western Reserve law professor Jonathan Adler emphasized that Kavanaugh’s “opinion in Seven-Sky was clearly about how the penalty should be treated for purposes of the Anti-Injunction Act,” and did not insist that the mandate “was a tax for constitutional purposes.”

“I don’t think it implicates questions about whether he’s an originalist,” Alder said.

Supreme Court nominations can be difficult, and there may be good arguments against Kavanaugh, but he did not uphold Obamacare in Seven-Sky, and that is a sigh of relief.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member