A technological breakthrough could enable a baby to develop in an artificial womb, allowing a mother to avoid abortion while saving the baby’s life. This would undercut the legal justification for abortion in Roe v. Wade, creating a fascinating legal dilemma. A bioethicist at Harvard University warned that it would undercut a woman’s “right to an abortion.”

“It could wind up being that you only have the right to an abortion up until you can put [a fetus] in the artificial womb,” I. Glenn Cohen, a bioethicist at Harvard Law School, told Gizmodo. “It’s terrifying.”

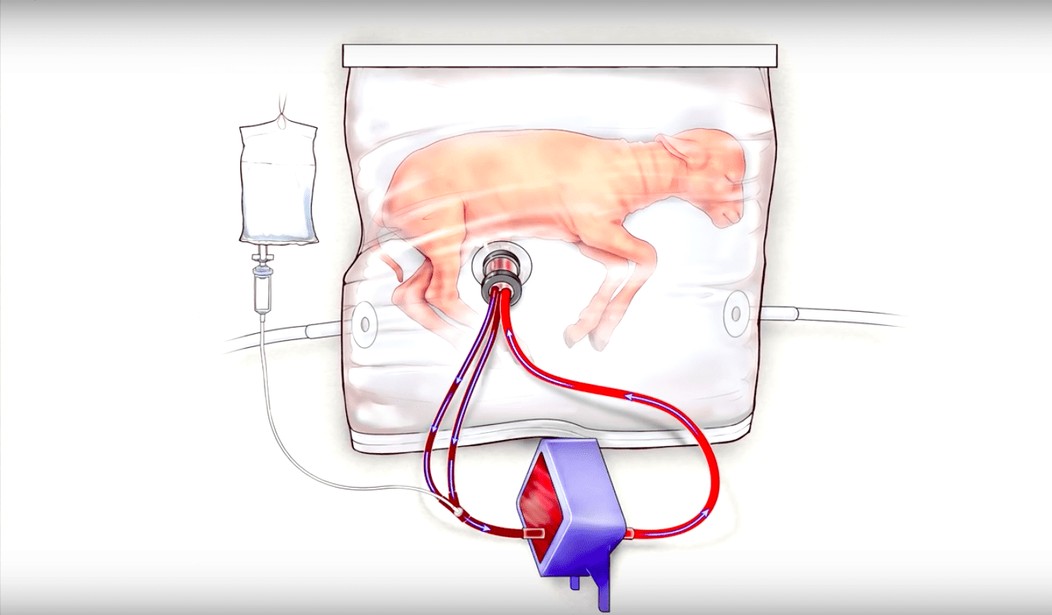

Cohen published a report Friday discussing the legal ramifications of a major breakthrough scientists had in April. A research team led by Alan Flake from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia successfully incubated eight premature baby lambs in an external womb resembling a high-tech ziplock bag. By April, the oldest lamb was nearly a year old and still seemed to be developing naturally.

It may take between five years and a decade before such technology can be used on premature human infants, but the results suggested that it could indeed keep premature babies alive before birth. If the technology becomes reliable and cheap enough, it could become a kind of substitute for abortion.

Gizmodo’s Kristen Brown explained that this technology could save the lives of the 30,000 or so babies each year born earlier than 26 weeks into pregnancy. But it could also complicate “and even jeopardize” the Supreme Court’s 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade that women have a right to an abortion before their baby reaches the point of viability.

“The Supreme Court has pegged the constitutional treatment of abortion to the viability of a fetus,” Cohen explained. “This has the potential to really disrupt things, first by asking the question of whether a fetus could be considered ‘viable’ at the time of abortion if you could place it in an artificial womb.”

In other words, if a woman decided to get an abortion to avoid carrying the child to term, she wouldn’t have to kill the fetus — the fetus could be removed and placed in an artificial womb to develop fully. This would save a life, and it would redefine the legal setting behind abortion.

Viability has already changed in the past few decades. A normal human pregnancy lasts about 40 weeks. In 1973, when the Supreme Court ruled abortion legal, the Court defined viability as a fetus’s ability to live outside of the womb. At the time, the Court said viability typically began at some point during the third trimester, which begins at 24 weeks.

In 1992, the Court reaffirmed viability as key to restricting a state’s power to regulate abortion. Today, viability ranges between 22 and 24 weeks by state, but no state can enforce a ban on abortion at any stage of development if a woman’s health is at risk.

Cohen suggested that the artificial womb technology could save the lives of fetuses as early as 18 weeks. This would push viability back, changing the way women go about the process of abortion — or fetus transfer, keeping the child alive.

In his article, Cohen presented three possible legal interpretations. The state may “prohibit abortion outright only after viability but that it may require transfer to an artificial womb instead of abortion for women between eighteen weeks and viability.”

Another possibility is that the artificial womb changes the legal understanding of viability. “That is, while an eighteen-week-old fetus would not be viable under the traditional definition of viability, we may understand it as viable once transfer to an artificial womb was possible; therefore the state could prohibit both the transfer to an artificial womb and the abortion at eighteen weeks.” This would be the cruelest interpretation and therefore is least likely to come to pass.

Finally, Cohen presented another alternative, that states that would have prevented abortion outright after viability would be forced to allow women to transfer the fetus to the artificial womb as an alternative.

In his article, Cohen seemed to fear that pro-life activists and legislators, in their zeal to destroy the lives of women, would abuse this possibility of keeping babies alive in order to ruin women’s lives. Contrary to the irrational fear of pro-life activists as secret misogynists, there is no evidence to suggest pro-life legislators would use the new technology merely to outlaw abortion, without allowing another possibility.

Most likely, pro-life legislators would champion the artificial wombs as a possibility. Pro-life non-profits should raise money to help women who would get abortions transfer their babies into artificial wombs. A new legal apparatus should be created by which mothers and fathers surrender their paternal rights and allow full adoption for babies born in artificial wombs.

While pro-abortion activists may fear that this new technology could remove a “woman’s right to choose,” it could arguably be the perfect solution to the complex moral problem of abortion.

As Cohen noted, both legally and ethically, “the abortion right has been most vigorously defended as a right not to be a gestational parent, not as a right not to be a legal or genetic parent.” The problem is, a woman does not want to be saddled with a life-altering pregnancy. Abortion allows her to avoid this, but so would the artificial womb.

“The right enjoyed by women is a right to stop gestating, not a right to end the existence of the fetus,” Cohen explained. “The artificial womb would allow women to exercise the first right without the second.”

Because of this legal situation, the artificial womb solves both the demands of pro-choice activists (for women to “control their own bodies”) and those of pro-life activists (for the fetus to survive).

Cohen is right to point out, however, that “defending the right to abortion when transfer is possible would change the moral terrain.” The argument of “‘my body, my choice’ would instead become a right to terminate the life of the fetus. A defense along these lines could still be possible on the philosophical level, but seems a much harder sell legally and politically.”

Naturally, the artificial wombs would present legal problems around maternal and paternal rights. Cohen cited the 1976 Supreme Court case Missouri v. Danforth in which the Court “rejected one state’s paternal veto on the provision of abortion on the ground that when a father and mother disagree on whether abortion should go forward, only one can prevail, and ‘as it is the woman who physically bears the child and who is the more directly and immediately affected by the pregnancy, as between the two, the balance weighs in her favor.'”

The transfer to the artificial womb would invalidate this argument, which is why the technology would require new legal structures regarding parental rights. As an alternative to abortion, a mother (and father) should be able to sacrifice her (and his) parental rights entirely, enabling easy adoption in such cases.

This new technology may undercut abortion, but it need not damage women’s rights. It may provide the impossible third way long sought by the pro-life and pro-choice movements. If a woman can be free of the challenges of pregnancy without killing the baby, this could permanently solve the issue.

Naturally, the case will require a great deal of debate and the technology has not yet been developed. But this alternative should be welcomed, not resisted.

Watch a heartening video about this new breakthrough, from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member