They were the best of friends until they weren’t. For ten years, they couldn’t even talk to each other. And then they became friends again. This is the story of the topsy-turvy relationship between two of the United States of America’s most well-known and influential founding fathers — John Adams and Thomas Jefferson.

They founded a country. Each took his turn running that country as president, and both gave us a sense of what politics can do to people.

Historians describe them as collaborators and competitors, allies and adversaries, friends and estranged rivals.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson came from different places in society. Adams was born in 1735 in Braintree, Mass. He was the son of a humble New England farmer. To call him strong-willed would be kind. He was very difficult to get along with. He’d be intense, argumentative, rigidly moral (and judgmental), and almost constantly preoccupied with what could go wrong or what was going wrong.

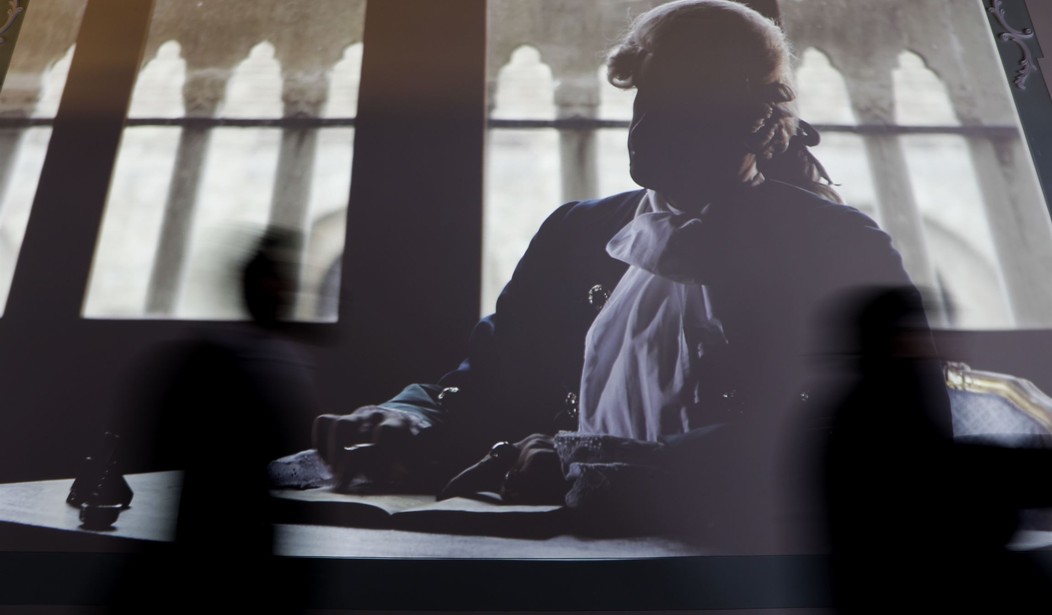

Jefferson was a little younger. He was born eight years after Adams in 1743. His childhood was that of a plantation aristocrat in Virginia. People who knew him at the time described him as a gentleman, reserved, very intellectual, and supremely self-assured. As the author of the Declaration of Independence, he wouldn’t have surprised you with his exceptional power of reason and his passion for one’s natural rights.

The Revolutionary War brought these two hard-headed, Type A personalities together.

At the Second Continental Congress in 1775, Adams was in his element. He was loud, persistent, and oftentimes irritating to others at the event. By contrast, Jefferson was quiet, precise, and observant. Adams, though, had a keen eye for what was needed, and he saw almost immediately in Jefferson, something the new republic desperately needed — a world-class writer. Adams pushed for Jefferson to write the Declaration.

The two collaborated on what would become the Declaration we know today, but to get to that point, Adams needed to fight for it in Congress, and the two needed to listen to the concerns and sensitivities of the other members, but not so much so that they’d compromise its power. These two gave the revolution its voice.

This was their honeymoon period, where Adams was generous with praise of Jefferson’s intellect, while Jefferson pointed out Adams’s courage and tireless commitment to the cause. These were two very deep allies as well as friends. They were bound by a purpose: to create a new nation.

During the war and in its wake, both men spent time in Europe, helping the U.S. to find its place in the world’s order. It was one thing to envision and fight to create this country, and another to make sure the rest of the world took it seriously and respected it.

As diplomats, differences in temperament and worldview emerged and started to cause a rift between the men. Jefferson loved everything about Paris — the architecture, the culture, and the salons. Salons were private intellectual gatherings held in homes where the host was a woman from the upper class. This is where leading thinkers, writers, artists, scientists, and politicians would meet to exchange ideas and stroke each other’s egos.

Adams, on the other hand, did the same things in Europe that he did in America. He worked furiously, harder than most, and so when he looked around, he felt underappreciated.

By the 1790s, these long-time friends became rivals.

The United States, still in its infancy, had to determine how strong the federal government should be, how close America should be to Britain or France, how much power the president should have, and what role political factions should play in a healthy democratic republic.

Time and again, Adams and Jefferson landed on opposite sides of nearly every issue.

Adams wanted to avoid chaos and mob rule, so he aligned with the Federalists. He wanted more centralized authority. Jefferson was a natural skeptic when it came to authority, and so, his biggest fear was the creation of a tyrannical government. He trusted people over government.

The two dug in on their respective sides. They attacked each other in the press, in speeches, and at any time each had an audience who would listen.

In 1800, Adams was the sitting president. Jefferson was his vice president. They ran against each other for president, and Jefferson ended up winning. They accused each other of tyranny, atheism, corruption, and even treason. This made for good copy in the press. After Jefferson won, Adams left Washington before Jefferson was even inaugurated. He refused to attend.

It was ten years before they would speak or correspond again. During this time, each had time to put it all into a better context. They were retired from public life now. As time passed, they could see that democracy is messy, and yet if done right, a country that lives by it is resilient.

It was Dr. Benjamin Rush who primarily brokered a ‘truce’ between Adams and Jefferson, but others close to them intervened as well. Slowly, the two were led back to speaking terms.

In 1812, Adams broke the ice by writing to Jefferson in a letter, “You and I ought not to die, before we have explained ourselves to each other.”

That was all it took for the two to reunite through regular correspondence and a friendship that would last until both men died on the same day, July 4, 1826. In this final chapter of their lives, Adams and Jefferson exchanged more than 150 letters. If you read any of them, you will see the exchanges were respectful and even affectionate, not just for each other, but for the country they founded. Their baby, if you will.

They’d get into detail about philosophy, religion, and other deep topics. They’d often disagree but with respect. They debated human nature, the dangers of aristocracy, and the future of the country. Perhaps not surprisingly, they reminisced about the Revolution, and they shared a laugh at prior grievances.

In the course of their correspondence, Adams admitted his temper was an issue. Jefferson acknowledged that his own political passions had distorted his thinking.

In 1816, one letter from Jefferson to Adams provides a sense of how close the two men had become. He wrote in closing, “I will dream on, always fancying that Mrs Adams and yourself are by my side…”

July 4, 1826, was the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration, and that’s when Adams and Jefferson died just hours apart.

Jefferson was the first, taking his last breath at Monticello. Four hours later, Adams reportedly said his last words, “Jefferson still lives,” not aware that Jefferson had already died.