It wasn’t the jab. Nor the uppercut, hook, or overhand right. Yeah, they swapped sledgehammers for 41 rounds, blasting each other into broken, beaten bits, but in the end, those weren’t the weapons that tore the deepest.

It was words.

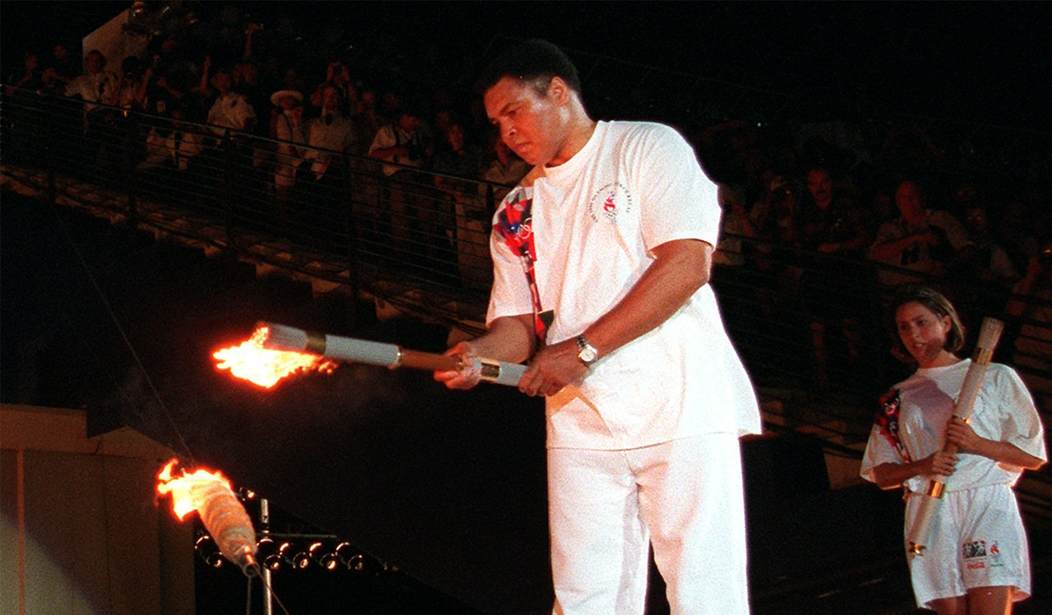

Fifty years ago today was the “Thrilla in Manila” — the legendary crescendo to the Joe Frazier-Muhammad Ali trilogy. ESPN ranked it as the fifth-greatest sporting event of the 20th century.

If you’ve never seen it, hang your head in shame. Here’s a link:

The Muhammad Ali legend is now indistinguishable from Muhammad Ali. Separating the man from the mystique is harder than floating like a butterfly and stinging like a bee: He’s the Greatest of All Time.But once upon a time, he was still a work in progress.

Cassius Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali after besting the unbeatable Sonny Liston in 1964. He courted publicity — as well as controversy — wherever he went.

But inside the ring? Ali was unbeatable.

He flattened Liston in their rematch (the “phantom punch”), embarrassed ex-champ Floyd Patterson, and made mincemeat of the heavyweight division. They weren’t competitive fights; they were showcases for the mastery of his craft.

He’d literally tell you which round he’d KO his opponent — and then do it.

Next came the Vietnam War draft. Ali declared himself a conscientious objector, citing religious reasons, but the government felt otherwise. The combination of legal limbo and public uproar led to Ali being stripped of his title and barred from fighting for 3.5 years.

And when he returned to his sport, the heavyweight division had a new king: Smokin’ Joe Frazier.

To younger fans, Frazier was similar to Mike Tyson: They were both short, compactly-build, and thunderous punchers. Each was capable of spectacular knockouts.

And both won the title as undefeated, unblemished warriors.

So, when Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier met in the “Fight of the Century” on March 8, 1971, it marked the first time in history that two undefeated heavyweights — each with a legitimate claim to the world title — would settle their differences in the ring.

It was one of those moments where the whole world came to a stop: Everyone wanted to see ‘em fight!

Joe Frazier won by unanimous decision, flooring Ali in the 15th round. It was the first time Ali had tasted defeat since he was a 19-year-old amateur.

Smokin’ Joe Frazier was on top of the world. Ali pleaded for a rematch, but Frazier declined: In his mind, he had already proved his point.

And besides, Frazier was starting to dislike Ali.

They hadn’t always been enemies. Once upon a time, when Ali was barred from fighting and Frazier was making a good income as champion, Joe actually lent Muhammad money. According to Frazier, Ali was respectful and appreciative in private, telling him how much money they’d make together in the ring one day.

Furthermore, Frazier understood boxing economics: Promoting the fight is, was, and will forever be a huge part of the fight game. Nobody gets paid if the public doesn’t care and the media ignores you.

Frazier knew how to promote, too. He did interviews, made guest appearances, and even sang songs on national TV. (For a singer, he was… a very good boxer.)

But Ali pushed things too far.

After Joe Frazier was blasted into orbit by future grill entrepreneur George Foreman — that’s the fight with the famous Howard Cossel line, “Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!” — he suddenly found himself on the outside looking in. Big George was now calling the shots, making the big fights.

And all of a sudden, a rematch with Ali made a lot more sense.

They met once again in Madison Square Garden, but they almost came to blows before that: Five days before their fight, they shared the stage on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, and ended up in an impromptu wrestling match.

The wrestling match was a draw. But in the ring, Ali won via unanimous decision.

Muhammad Ali leveraged his victory over Joe into a title bout with Big George Foreman in Zaire. You know the fight by its nickname: The Rumble in Jungle.

Ali “shook up the world” and knocked out Foreman, winning the heavyweight title for the second time.

This was the backdrop to Ali versus Frazier III, a.k.a. “The Thrilla in Manila.” By some estimates, there were more than a billion viewers around the planet.

Ali received $9 million; Frazier was paid $5 million. The money was guaranteed by Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos, who — similarly to Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire — was willing to spend their the country’s money to boost his prestige and tourism.

For Frazier, what angered him the most wasn’t the difference in pay. It was that the money was guaranteed.

Because, if it’s already guaranteed, there’s no need for mean-spirited PR campaigns.

During the prefight publicity, Muhammad Ali put on a helluva show: He mugged every camera and yapped on every microphone. At one point, he pulled out a toy gorilla and declared it would be “a killa and a thrilla and a chilla, when I get that gorilla in Manila.”

And more than once, Ali compared Frazier to a monkey.

The fight itself is epic, extraordinary, and borderline preposterous: For 14 rounds, each man gave the other his absolute best. At one point, Ali whispered to his trainer, Angelo Dundee, “This is the closest I’ve ever been to dying.”(The link to the fight is above: What are you waiting for? WATCH IT!)

Eddie Futch, Joe Frazier’s trainer, stopped the fight before the beginning of the 15th round. Futch was one of the true gentlemen of the fight game and loved Frazier; after all that carnage, even one more round wasn’t worth the long-term risk.

“I want him, boss!” rasped Frazier, begging to continue.

Futch shook his head. “Sit down, son. It’s all over.”

In later interviews, Futch explained why he threw in the towel: “[Joe]’s a good father and I want him to see his kids grow up.”

And by all accounts, he was. By all accounts, he did. (Random fact: When I booked Joe Frazier for a radio interview in the 1990s, his son, Marvis, was the one who facilitated it.)

Journalist Jerry Izenberg, who covered the fight, participated in a retrospective with The Jerusalem Post:

The build-up was ugly, and not only in the taunts. Ali would walk around Manila punching a small toy gorilla, referring to it as Frazier. Forever the poet, "It will be a killa and a thrilla and a chilla, when I get that gorilla in Manila," he would chant.

Izenberg points to the human damage of Ali's invective, how kids in school bullied Frazier's son, Marvis, and he would return home in tears, calling him the son of a "gorilla." "That," Izenberg said bluntly, "had nothing to do with the first two fights. It had to do with the gorilla." And it had an effect on Frazier.

In Frazier’s 1996 autobiography, he wrote:

Truth is, I'd like to rumble with that sucker again — beat him up piece by piece and mail him back to Jesus. ... Now people ask me if I feel bad for him, now that things aren't going so well for him. Nope. I don't. Fact is, I don't give a damn. They want me to love him, but I'll open up the graveyard and bury his ass when the Lord chooses to take him.

A Sports Illustrated story shared an anecdote about the time a 10-year-old girl asked Frazier if he ever beat Muhammad Ali:

A scowl passed like a shadow down Frazier's face, and for a long moment he sat reeling in his chair, leaning back as his eyes rolled wildly from side to side, and he groaned, groping for words: "Agghh....Ohhh....Agghh...."

Finally, Frazier told the little girl, “We locked up three times. He won two, and I won one. But look at him now. I think I won all three.”

From Smokin’ Joe’s perspective, the money in Manila was guaranteed by the Marcos. They had already made bank, so there was nothing left to promote! Sure, maybe if ticket sales were slow, they’d have to manufacture some kind of feud or gin-up a storyline, but this event didn’t need any hyperbole.

So what was the point in Ali running around, calling him a gorilla and making his kid cry?

From Ali’s perspective, the promotion never ended; the circus went on forever. He wasn’t just selling tickets or promoting a fight; he was building them both into legends.

And besides, it was all in good fun. Right?

Ali did try to make amends. He tried in the arena directly afterwards:

A benumbed and exhausted Ali, his lips scraped raw, lay on a cot in his locker room in Manila and summoned Marvis Frazier, Joe's 15-year-old son, to his side. "Tell your dad the things I said I really didn't mean," Ali said.

Marvis reported back to his father. "He should come to me, son," Joe told him. "He should say it to my face."

Joe's right (to be bitter). I said a lot of things in the heat of the moment that I shouldn't have said. Called him names I shouldn't have called him. I apologize for that. I'm sorry. It was all meant to promote the fight.

Frazier never forgave him. The wound was too deep.

And it had nothing to do with their fists.