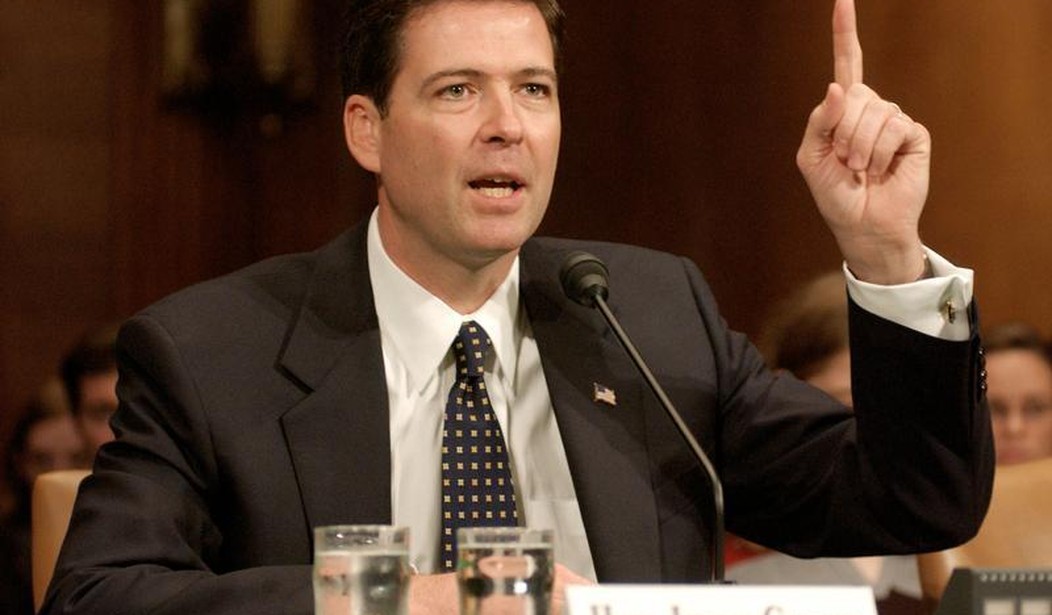

WASHINGTON –Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey warned about the dangers of “going dark” as new encryption technologies threaten to make it harder for law enforcement to access information from people’s cell phones and other communication devices.

In a recent speech at the Brookings Institution, Comey spoke about the challenges facing law enforcement as electronic communications become more advanced and diverse. He said a 20-year-old law dealing with how the government can intercept and monitor communications must be updated to deal with new technologies.

“The law hasn’t kept pace with technology,” Comey said. “This disconnect has created a significant public safety problem. We call it ‘going dark,’ and what it means is this: those charged with protecting our people aren’t always able to access the evidence we need to prosecute crime and prevent terrorism.”

The Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA) currently mandates telecommunication companies to build systems that can be wiretapped. Law enforcement agencies can then intercept communications with a court order.

The law, however, does not cover some companies providing Internet-based communications, such as Google, Facebook, and Apple.

In the wake of the revelations by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, technology companies have responded to the public backlash against government surveillance. The disclosures revealed the extent of U.S. government collection of electronic data, including phone calls and data stored on Google and Yahoo servers.

Google and Apple have recently started selling mobile devices with operating systems that will encrypt all information by default, shielding documents, contact lists, and photos from the government or hackers. The phones will automatically scramble data so that a digital key kept by the owner is needed to unlock it. This means that the companies could not respond to a legal warrant for access to a suspect’s phone because they would not be able to break the encryption.

The new encryption, however, would not affect information obtained by wiretaps, such as phone conversations, text messages, or emails.

Comey called on Congress to update CALEA, adding that this “regulatory or legislative fix” should subject all companies to the same standard “so that those of us in law enforcement, national security and public safety can continue to do the job you have entrusted us to do.” He said any revision to the law should require, among other things, that communications providers unscramble messages if presented with a court order.

The FBI faces two main challenges when it comes to electronic communications: interception of “data in motion,” phone calls, emails, live text or chat sessions, and accessing data stored on devices, such as email, text messages, videos, or photos, what the agency calls “data at rest.”

Comey said criminals whose phones are being monitored can evade wiretaps by making calls over Wi-Fi, switching apps they are using to exchange information, and even switching cellular networks on the fly.

“We may not have the capability to quickly switch lawful surveillance between devices, methods and networks. The bad guys know this. They’re taking advantage of it every day,” Comey said.

While the tech companies’ actions are understandable given that they are a response to market demand, he added, “the place they are leading us is one we shouldn’t go to without careful thought and debate.”

“Encryption isn’t just a technical feature. It’s a marketing pitch. But it will have very serious consequences for law enforcement and national security agencies at every level,” he said. “If the challenges of real-time data interception threaten to leave us in the dark, encryption threatens to lead us all to a very, very dark place.”

Privacy advocates say that creating a means of access for law enforcement – what Comey called a “front door” – increases the chances that those with ill intentions can find a way into that same data.

Civil liberties groups say federal law protects the rights of companies to add encryption features with no back doors.

“Director Comey is wrong in asserting that law enforcement cannot do its job while respecting Americans’ privacy rights. Indeed, federal law explicitly protects the right of companies to add encryption with no back doors,” said Laura Murphy, head of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Washington legislative office, in a statement.

Comey, who likened encrypted data to a safe that cannot be cracked, said the FBI is committed to a front-door approach that the agency can use with “clarity and transparency” to intercept communications.

He said Snowden’s revelations have generated many misconceptions among the public about the government’s ability to do surveillance and what type of information it collects.

“Some believe that law enforcement, and especially the FBI, has these phenomenal capabilities to access any information at any time, that we can get what we want, when we want it by flipping a switch. That is the product of too much television,” Comey said.

Google said in a statement the government can still obtain the data through other means.

“While we won’t be able to provide encryption keys to unlock phone data directly, there are still a number of avenues to obtain data through legal channels,” the statement said.

Apple CEO Tim Cook said recently that the company could not provide iPhone data to the government even with a subpoena.

“It’s encrypted and we don’t have the key,” Cook said.

The FBI chief’s call is expected to usher in a battle on Capitol Hill, reminiscent of the “crypto war” of the 1990s, over whether or not tech companies need to give the government access to their users’ data.

Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) tweeted on Friday that asking Americans for more surveillance power would be a “tough sell” for the FBI and the Justice Department.

“I’d be surprised if more than a handful of members would support the idea of backdooring Americans’ personal property,” said Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.).

Join the conversation as a VIP Member