The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) are currently building a prototype of a Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket (VASIMR) that would theoretically be capable of traveling from the Earth to Mars in about 40 days.

Rosatom’s Troitsk Institute in Moscow unveiled a "pulse plasma" rocket in 2025 that would be even faster, capable of traveling from Earth to Mars in 30 days.

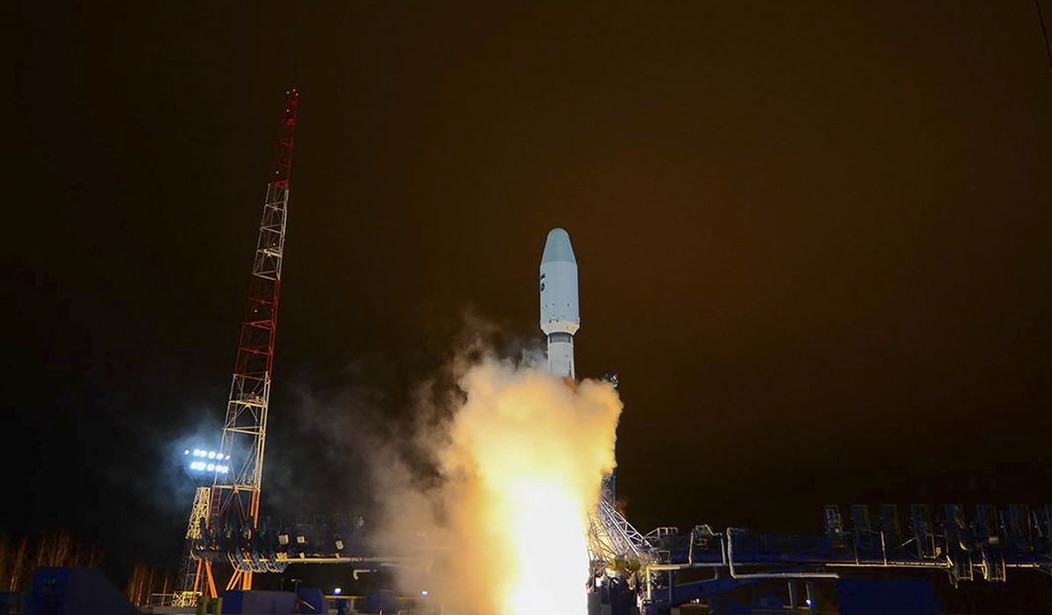

The days of watching rockets fueled by liquid oxygen mixed with liquid hydrogen blast into space are coming to an end. The mixture is potent but wildly inefficient. The Artemis II rocket carries 5.5 million pounds of rocket fuel to lift 7 million pounds off the launch pad. Weight is measured in dollars, so the more efficient the fuel, the cheaper it will be to carry cargo and people into space.

Plasma engines use radio waves to heat the plasma to millions of degrees and magnetic fields to propel it. Popular Mechanics reports that the Russian pulse rocket's "magnetoplasma accelerator provides a specific impulse (the acceleration of hydrogen particles) of up to 100 kilometers (62 miles) per second and a power output of 300 kilowatts, which Rosatom describes as 'unmatched by any existing technology.'”

The big advantage of plasma rockets, beyond their enormous power, is that the fuel needed for a long flight to Mars or the moons of Jupiter is a fraction of what would be needed in a liquid-fueled rocket. The plasma rocket would require only 1/10 or 1/20 as much fuel as a liquid-fueled rocket.

Chemical rockets are less efficient; about 98% of the rocket's starting mass must be fuel just to reach the destination. The efficiency of a plasma rocket allows up to 70% of the spacecraft's initial mass to be actual payload (people and cargo) rather than just fuel.

Russia claims its plasma engine will be ready by 2030, something even most Russian observers scoff at.

In classic, schoolyard “anything you can do I can do better” fashion, the Russian corporation claims that its plasma rocket could theoretically reach Mars in just one month. If all goes according to plan, the officials say they want a flight-ready version of the engine by 2030. Of course, that’s a big ask, as Russia’s space industry isn’t exactly thriving. In the summer of 2025, Igor Maltsev—the head of RSC Energia, one of Russia’s largest spacecraft manufacturers—gave a somber view of the company’s space ambitions, saying that they “need to stop lying to ourselves and others about the state of affairs.”

The Soviet Union may have died 30 years ago, but the lies are still the same.

Regardless, the most exciting era in the history of space exploration is about to unfold with rockets that travel faster, go farther, and open space travel to a new generation of explorers/exploiters who will help usher humans into a new era.

Whether or not Russia will actually field this “unmatched” plasma engine by 2030 doesn’t change the fact that plasma engines are being vigorously pursued by countries around the world. The Xi’an Aerospace Propulsion Institute in China, for example, similarly states that it is developed a groundbreaking “high-thrust magnetic plasma thruster” (though this was reported by state-owned media), and research from Wuhan University in October is investigating ways to bring this technology to aircraft engines.

An interim booster that is likely to become the workhorse of interplanetary travel is a rocket that uses a nuclear reactor to heat hydrogen, which then rapidly expands, and the energy is shot out of the nozzle. This hydrogen-powered rocket is also far more efficient than the current liquid-fueled rockets.

Naturally, if you say the word "nuclear," the anti-nuke crowd has a hissy fit. In this case, the fear is that the rocket will explode or crash on takeoff, spreading nuclear material all over the Florida Everglades.

In fact, because liquid-fueled rockets require so much more mass to be dedicated to fuel (about 98% of the rocket's starting mass), they are fundamentally more expensive and carry massive amounts of volatile chemical energy compared to plasma or nuclear-hydrogen designs.

Certainly, by the mid-2030s, we'll see several different kinds of plasma rockets either in the experimental stage or being used to send probes to deep space. They aren't likely to be government-owned rockets either. The entrepreneurial spirit will make space travel cheaper and faster than was thought possible in the 1960s.