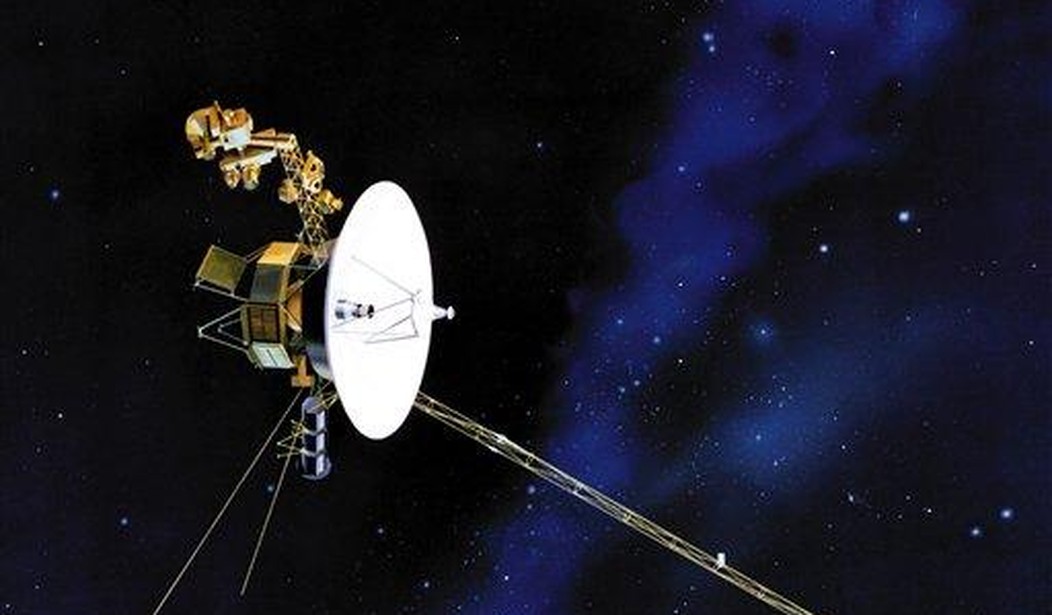

On Sept. 5, 1977, Voyager 1 blasted off from Cape Canaveral on the most ambitious unmanned mission in history. Her sister spacecraft, Voyager 2, was launched 16 days earlier. She would make the unprecedented trip to the outer planets.

In the early days of the Space Age, scientists realized that, given the proper planetary alignments, it might be possible to use the gravity of one planet to change a spacecraft's trajectory and send it to another without expending any fuel. The mission to send two spacecraft to the outer solar system, including flybys of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, was approved, and a tentative launch window of 1977 was targeted. It was then that the planets would be in perfect alignment for the attempt at a "Grand Tour," as planetary scientists called it.

Voyager 2's historic visits to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune expanded human knowledge of our planetary neighbors immeasurably and are still sending data back about its journey.

Voyager 1 also visited Jupiter and Saturn, making breathtaking discoveries about the moons of both planets. Then, using a gravity assist from Saturn, Voyager 1 was thrown at unheard of speeds (more than 38,000 MPH) toward the edge of the solar system into interstellar space.

Voyager 1's launch occurred 17,649 days ago; 48 years, 3 months, and 26 days have passed, and Voyager 1 continues to make astonishing discoveries. NASA announced this week that Voyager 1 will have traveled one light day from Earth in 2026.

The term light-day refers to the distance at which it will take 24 hours for a signal or command traveling at the speed of light to reach the spacecraft from Earth, said Suzy Dodd, Voyager project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. One light-day is equivalent to 16 billion miles (26 billion kilometers).

So if Voyager’s team is asking the spacecraft to do something once it reaches that point, it will take another day for Voyager to respond.

“If I send a command and say, ‘good morning, Voyager 1,’ at 8 a.m. on a Monday morning, I’m going to get Voyager 1’s response back to me on Wednesday morning at approximately 8 a.m.,” Dodd said.

How are Voyager 1 and 2 still working? Engineers have been turning systems off one at a time over the last 48 years to conserve power and try to keep the spacecraft warm in the cold, blackness of space.

“The distance that we are away from the Earth takes much longer to get a signal there, and the signal strength just dissipates,” Dodd said. “It takes multiple antenna arrays to gather that signal back.”

The 1970s technology is amazing. The two spacecraft were designed to be as self-sufficient as possible.

“If they get something going wrong, they can put themselves in a safe state so that they can wait until we’re able to talk to the spacecraft and figure out what the problem is and resolve that issue,” Dodd said.

NASA hasn't turned off all the instruments. The spacecraft were able to detect and record an astonishing zone of a 30,000 to 50,000 degree "wall of fire" beyond the dwarf planet Pluto.

Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause on 25 August 2012, becoming the first spacecraft to leave the heliosphere. Voyager 2 followed on 5 November 2018. As each passed through this boundary, mission teams recorded a sharp drop in solar particles and a corresponding rise in high-energy cosmic rays, a clear signal of entry into interstellar space.

Both spacecraft also measured significant increases in local plasma temperatures. These temperatures, although extreme in magnitude, were recorded in a region with ultra-low particle density. This means the plasma is high-energy but does not transfer heat effectively, allowing the spacecraft to remain undamaged.

In a NASA summary, officials confirmed that the extreme energy recorded at the boundary does not threaten the probes due to the near-vacuum conditions. The heat results from plasma particles moving at high velocities, rather than from dense collisions.

The heliopause marks the balance point where the outward pressure of the solar wind is countered by the inward pressure of the interstellar medium. The space just beyond this boundary, where the temperature jump occurs, lies within what NASA classifies as interstellar space.

Both probes cost a total of $1 billion. Considering the incredible discoveries both probes have made (liquid water beneath the surface of Europa), the extraordinary engineering, and the nearly 50-year lifespan of these probes, NASA and the American taxpayer got more than their money's worth.