Robert Oppenheimer, the enigmatic leader of the Manhattan Project that built the first atomic bomb, reportedly broke out in a cold sweat when a young Los Alamos scientist, Edward Teller, told him they had discovered that some lighter elements, like hydrogen, could release energy by "fusing" together during the process of liberating atomic energy by nuclear fission.

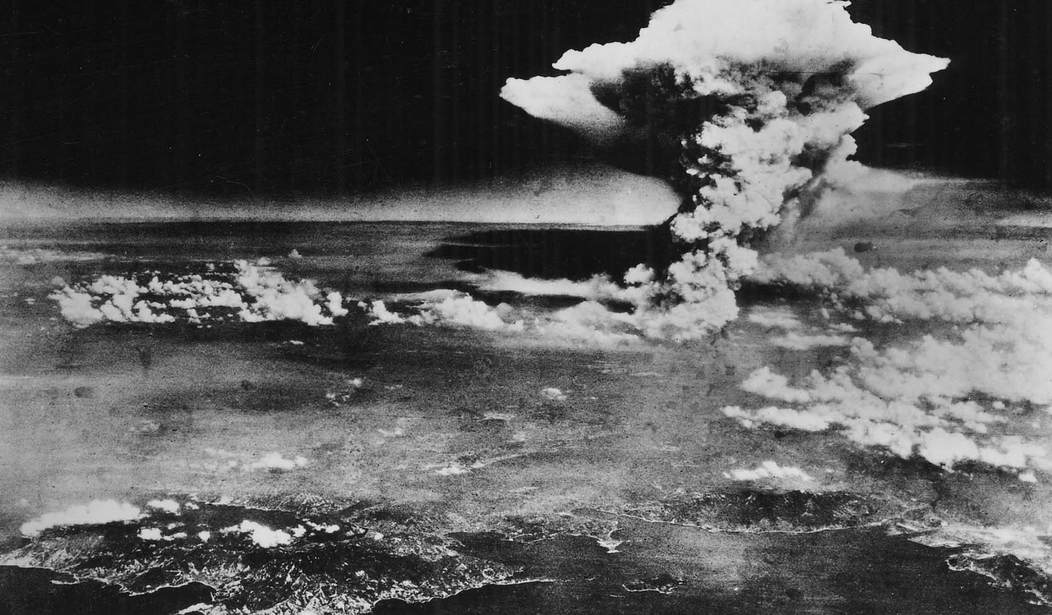

This was in 1943, less than two years before the "Trinity" test of the first atomic bomb. While the fusion process was known, the possibility that the enormous temperatures initiated by detonating a fission bomb (tens of millions of degrees Celsius for a millionth of a second at detonation) could fuse hydrogen and some other lighter elements, leading to the catastrophic ignition of the atmosphere. The resulting fireball would circle the globe, killing most life on Earth.

Oppenheimer felt obligated to take this information to Arthur Compton, a brilliant, Nobel Prize-winning physicist who ran the metallurgical department at Los Alamos and was one of the most influential scientists working on the Manhattan Project. Oppenheimer traveled by train from New Mexico to Michigan to brief Compton on the discovery.

Nobel Prize-winning writer Pearl Buck (The Good Earth) interviewed Compton after the war about his conversation with Oppenheimer regarding the frightening scenario. He told Buck, "...it would be 'better to accept the slavery of the Nazis than to run the chance of drawing the final curtain on mankind!'”

Buck's article, “The bomb—the end of the world?” which appeared in The American Weekly in 1959, caused a sensation. Compton told Oppenheimer that he thought the project should only proceed to conclusion if calculations gave a less-than three-in-a-million chance that an atomic bomb would destroy the world.

Oppenheimer believed that the three-in-a-million margin of safety had already been achieved. But what if their calculations were wrong?

Soon after his conversation with Compton, Oppenheimer reached the scientific conclusion that the runaway fusion reaction that could burn up the atmosphere wasn't possible.

It was Teller, another member of the Los Alamos team, who first raised the possibility of a “super-bomb” powered by thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen (more specifically, of the heavy-hydrogen isotope deuterium). The enormous temperatures needed to ignite fusion in the deuterium fuel would be created by a fission bomb—which then conjured up the specter of such a uranium bomb igniting the atmosphere. Teller proposed that it was possible for two nuclei of the isotope nitrogen-14 (nitrogen being the principal component of air) to fuse into various other elements, with a massive energy release.

But how likely was it really? “I didn’t believe it from the first minute,” Bethe said in a 1982 interview. If it had been him in Oppenheimer’s place, he attested, he would not have bothered to go to Michigan to discuss it with Compton. Bethe said that he found some unjustified assumptions in Teller’s calculations that made a runaway fusion process extremely unlikely.

"Teller, along with physicists Emil Konopinski and Cloyd Marvin, went on to further calculate the chances, concluding that there was, after all, no danger, even with very generous estimates of the highest temperatures a fission bomb would generate," writes Phillip Ball in Nautilus.

“Ignition is not a matter of probabilities; it is simply impossible," wrote Bethe. Also, in a 1947 technical history of the Manhattan Project, historian David Hawkins wrote that the calculations made by Teller and his team showed that “no matter how high the temperature, energy loss would exceed energy production [by fusion] by a reasonable factor.”

The possibility of global atmospheric fusion was revisited when Teller's "Super Bomb" was being designed in the late 1940s. By then, it was an argument being used by those who opposed the construction of the Hydrogen bomb. Teller's "Super Bomb" dream came true in 1952 when the U.S. blew up a tiny island in the South Pacific.

Oppenheimer's hesitation was understandable. The scientists at Los Alamos were dealing with the primal forces of nature with only theoretical constructs to guide them. What if they were wrong? What if they miscalculated?

Fiction is full of stories about "mad scientists" who blow up the world inadvertently or otherwise. As a sidebar to history, it's a fascinating look at the scientific process as practiced by some of the most brilliant people who ever lived.