I have terrible handwriting. Check that — it’s not terrible, it’s awful. It’s unreadable. It’s illegible. A chimpanzee’s handwriting is brilliant in comparison.

That’s according to the good Sisters of Mercy who instructed me in the mysteries of cursive writing more than 60 years ago. In the beginning, my handwriting was slightly more legible. But as years passed, my opportunities to use the basic form of communication from my youth lessened considerably. Today, I try to write out a grocery list, and Sue invariably shows up at my office door to translate my chicken scratch.

“What is that?” she asks. “Is that Cheerios or Velveeta Cheese?”

Once I became passably good at typing, I rarely wrote anything out longhand. That’s pretty much the way it is for almost everyone alive today. The advent of the electric typewriter followed by word-processing machines and computer word-processing programs have killed off cursive writing.

Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

Modern educators claim that teaching cursive writing is a waste of time. But science would vehemently disagree. In fact, an article in The Atlantic shows that “Studies have found that writing on paper can improve everything from recalling a random series of words to imparting a better conceptual grasp of complicated ideas.”

For the same reason, I have never “listened” to a book, no matter who is reading it. Just like reading carries its own advantages — the “voice in your head” understanding everything all at once and completely without needing exposition — writing longhand forces you to organize your thoughts in ways that typing simply can’t do.

And taking pen to paper is actually the best way to learn by rote.

For learning material by rote, from the shapes of letters to the quirks of English spelling, the benefits of using a pen or pencil lie in how the motor and sensory memory of putting words on paper reinforces that material. The arrangement of squiggles on a page feeds into visual memory: people might remember a word they wrote down in French class as being at the bottom-left on a page, par exemple.

One of the best-demonstrated advantages of writing by hand seems to be in superior note-taking. In a study from 2014 by Pam Mueller and Danny Oppenheimer, students typing wrote down almost twice as many words and more passages verbatim from lectures, suggesting they were not understanding so much as rapidly copying the material.

Part of the note-taking study was a fascinating exercise in comparing the recall ability of hand-written note-takers and typists. Taking notes by hand was superior to those who typed. “The effect even persisted when the students who typed were explicitly instructed to rephrase the material in their own words. The instruction was ‘completely ineffective’ at reducing verbatim note-taking, the researchers note: they did not understand the material so much as parrot it.”

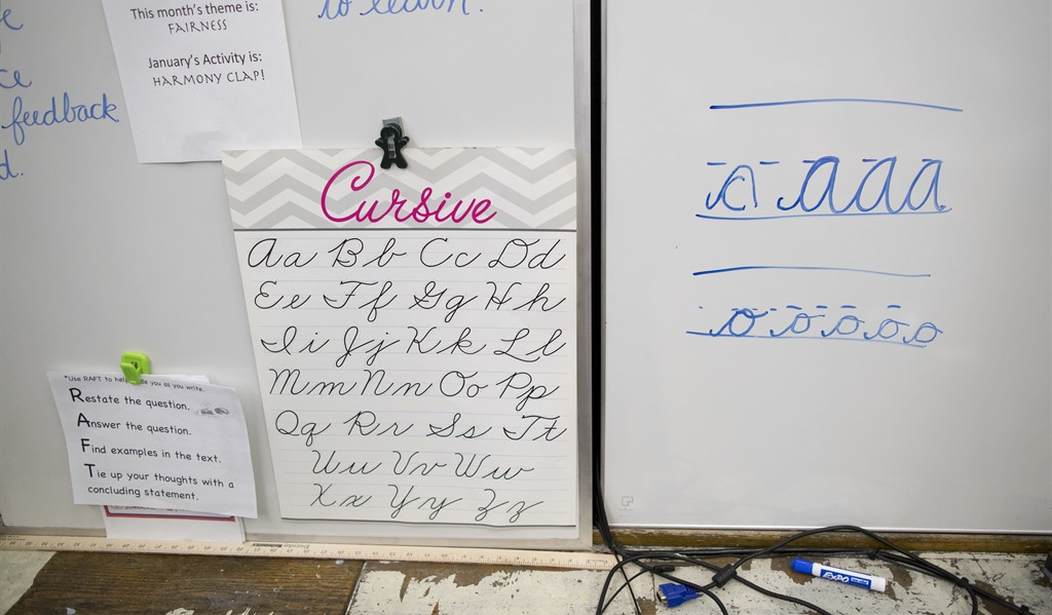

After some schools banned or curtailed instruction in cursive writing, there was a surprising movement by researchers and educators to bring it back after studies showed the many benefits of writing by hand.

Many studies have confirmed handwriting’s benefits, and policymakers have taken note.Though America’s “Common Core” curriculum from 2010 does not require handwriting instruction past first grade (roughly age six), about half the states since then have mandated more teaching of it, thanks to campaigning by researchers and handwriting supporters. In Sweden there is a push for more handwriting and printed books and fewer devices. England’s national curriculum already prescribes teaching the rudiments of cursive by age seven.

My arthritic hands make any cursive writing at length impossible. Grocery lists will have to serve as my connection to a lost era. Indeed, I wonder how these kids are going to be able to sign their name on a check, or a contract, or their marriage license? Will they have to “make their mark” as illiterate people did in the 19th century?

Like many of life’s annoyances and problems today, I probably won’t be around to see how it all turns out.