BioNTech co-founder Uğur Şahin told the BBC that it will be a hard winter as the coronavirus will continue to spread and the vaccine developed with Pfizer “will not have a big impact on the infection numbers.” But with 300 million doses being distributed by April, Şahin thinks that if everything goes well, “we could have a normal winter next year.”

He added that “what is absolutely essential is that we get a high vaccination rate before autumn/winter next year … so all the vaccination and immunization approaches must be accomplished before next autumn — and I’m confident that this will happen because a number of vaccine companies are helping us to increase the supply — so that we could have a normal winter next year.”

What’s “normal”? It’s a question that politicians will have to answer. It will be up to political leaders to lift lockdowns and restrictions. This may prove to be a problem for some who have gotten used to telling people how to live and what to do. They will not give that power up lightly.

And public health bureaucrats who have been the driving force behind these restrictions aren’t likely to give up their influence easily either. As long as the coronavirus remains a threat to some people — which will be forever — politicians and bureaucrats will try to maintain their control.

But there are technical problems that still need to be overcome. The vaccine must be refrigerated and shipped in glass containers that may be in short supply.

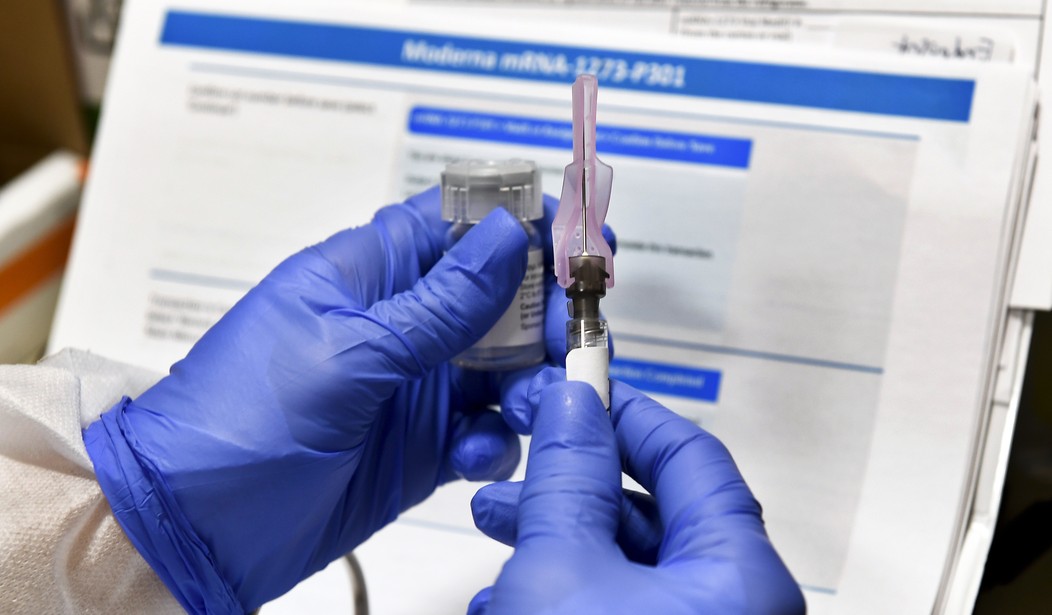

The main issue is that the vaccine, which is based on a novel technology that uses synthetic mRNA to activate the immune system against the virus, needs to be kept at minus 70 degrees Celsius (-94 F) or below.

“The cold chain is going to be one of the most challenging aspects of delivery of this vaccination,” said Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

“This will be a challenge in all settings because hospitals even in big cities do not have storage facilities for a vaccine at that ultra-low temperature.”

Even big-city hospitals can only store the vaccine at temperatures of -2 to -8 degrees. Otherwise, the vaccine only lasts five days.

The solution will be a challenge.

Pfizer spokeswoman Kim Bencker said the company was working closely with the U.S. government and state officials on how to ship the vaccine from its distribution centers in the United States, Germany and Belgium around the globe.

The detailed plan includes using dry ice to transport frozen vaccine vials by both air and land at their recommended temperatures for up to 10 days, she said.

Ten days is better than five, and would probably be OK for the U.S. and other Western countries, where distribution nets are well connected. But what about third-world countries where distribution networks are almost non-existent or deficient?

“If Pfizer’s is the only vaccine to be authorized in the next few months, we do worry about equity when it comes to spreading it to rural areas,” said Claire Hannan, executive director at the Association of Immunization Managers, a nonprofit organization representing state and local public health officials who handle vaccines.

Ultra-cold freezer supplies are already limited as hospitals scramble to stock up, Stefas said.

There’s a real danger that the vaccine will be unavailable for some Americans in rural areas. There are other vaccines in the pipeline that don’t need the super-cold storage of the Pfizer product, but the wait on those may be measured in months. And they may not be as effective as Pfizer’s 90 percent rate.

These challenges are not insurmountable, however, and with a little luck, by this time next year, the coronavirus could be a bad memory.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member