Life in the state of nature was once infamously described as “nasty, brutish and short.” Civilization was supposed to better things but it brought its own afflictions, ironically among which was government. The state, or those who led it, were capable of committing certain types of crimes, the most infamous of which are aggressive war, genocide, and ‘crimes against humanity.’ The flip side of chaos was too often tyranny. There is Samuel’s famous biblical warning against kingship, with its war:

And Samuel told all the words of the LORD unto the people that asked of him a king. And he said, This will be the manner of the king that shall reign over you: He will take your sons, and appoint them for himself, for his chariots, and to be his horsemen; and some shall run before his chariots. … And he will take your daughters to be confectionaries, and to be cooks, and to be bakers. … He will take the tenth of your sheep: and ye shall be his servants.

It is difficult to give an exact percentage of historical leaders who were homicidal dictators, but there have been quite a few. Some well-known examples include Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, and Mao Zedong. Beneath the first tier of homicidal dictators there is usually a deep bench of tinpot strongmen on the periphery of the great powers. Francisco Macías Nguema, Idi Amin, Charles Taylor, the North Korean Kims, Saddam Hussein, and Pol Pot are modern examples. Unlike nuclear superpower leaders, who were incentivized to act rationally, strongmen like Francisco Macías Nguema might actually have been crazy, as he went around proclaiming “there is no other God than Macías”.

Perhaps this should come as no surprise. In Kings, Conquerors, Psychopaths: From Alexander to Hitler to the Corporation, author Joseph N. Abraham argues that history is actually the annals of crime: “Conquest is murder and theft; Conquerors are vicious criminals; Conquerors become kings; Kings designed civilization; And we are the products of civilization.” Psychologists suggest that power attracts sociopaths or psychopaths. Psychos become heads of state because that’s where the power is.

But even official crime must have its rules or chaos will run rampant without a means of control; and if the state has a criminal aspect, it also has a hierarchical one. Gangsters can, and often do, regulate themselves. In some cases, they may establish their own hierarchies and rules, enforced through violence and intimidation. Those who have watched Mafia or Mexican cartel movies know they apportion territory and influence. Sovereigns police each other in much the same way.

War was a common method of resolving disputes. In ancient times, it was not uncommon for victorious powers to punish transgressions through collective responsibility. A losing state could be despoiled, its inhabitants sold into slavery and its king killed, often in a grisly fashion. But by the 19th century, such vengeance had become less prevalent in Europe and North America. Even though war persisted as a way of settling accounts, prior to the Nuremberg trials the idea of sovereign immunity and the defense of superior orders made it very difficult to hold government officials accountable for their actions in court. While state-caused disasters were small, they could be accepted as a necessary evil.

However, by the time of the Great War, conflict had become so destructive that a significant number of great states felt that it posed too great a risk to be borne anymore. Things had gotten out of hand. The years 1914-1918 were so ruinous that Kaiser Wilhelm was almost tried for war crimes in an effort that would foreshadow Nuremberg. Article 227 of the Treaty of Versailles intended that Kaiser Wilhelm would be tried by an international court for the “supreme crime against international morality and the sanctity of treaties.” But in the end, it never happened, and the Kaiser lived out his remaining years in the Netherlands.

It took the even greater carnage of WWII for states to renew the effort to police states. But Nuremberg itself highlighted one sad fact: “International Justice” for sovereigns was only feasible in a basically unipolar world or at the conclusion of a world war where one side is clearly triumphant over the other. This explains why so many Third World dictators fell at the end of the Cold War, when they were no longer needed as proxies, or why great power leaders from Germany and Japan could be hanged after WW2. The time was right for it to happen. There is a season for justice. Absent these special conditions, state crime could run unchecked.

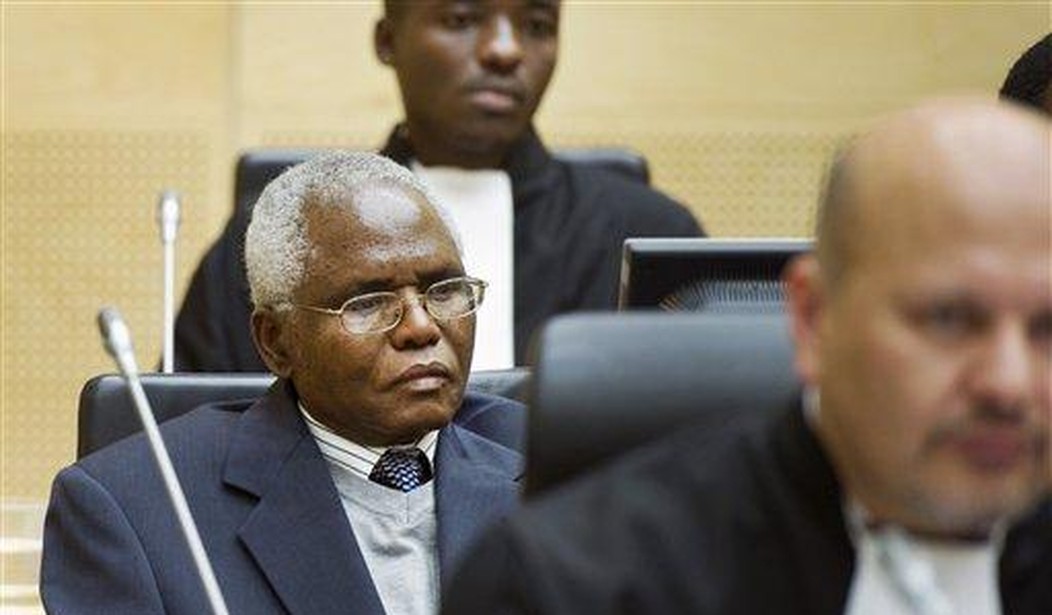

The inauspiciousness of the present explains the current toothlessness of the International Criminal Court (ICC). Since it was established in 2002, all 30 cases brought before the International Criminal Court have involved African nationals. Defendants Jean Pierre Bemba, Laurent Gbago, Charles Ble Goude, Dominic Ongwen, Bosco Ntaganda, etc. are doubtless people you have never heard of.

This circumstance makes the ICC arrest warrant for Russian president Vladimir Putin so singular. He is actually a somebody. The charges against Vladimir Putin are for “unlawful deportation and transfer of Ukrainian children from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation, contrary to article 8(2)(a)(vii) and article 8(2)(b)(viii) of the Rome Statute”. But since we are neither at the end of a big power war nor in a unipolar world anymore, even the New York Times admitted “the likelihood of a trial while Mr. Putin remains in power appears slim, because the court cannot try defendants in absentia and Russia has said it will not surrender its own officials.”

Related: ‘Project Fear’: Leaked Texts Reveal British Government’s COVID Terror Campaign

The question, if state criminality is to be resolved other than by armed conflict, is whether something in the calculus has changed, as with the Kaiser at the end of the Great War, to compel us to fashion some justice that works in all seasons. Perhaps the costs occasioned by the complexity of modern society, the density of its habitation, and the destructiveness of ‘limited war’ has made the defense of superior orders and sovereign immunity unaffordable. Recently the world has been through a crisis that would have rivaled a great war. In the last three years, somewhere between three and seven million people died in the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly caused by government biological experimentation. It cost the United States alone more than $16 trillion in economic damage. When the Ukraine War and the social upheaval occasioned by the politicization of institutions is added in, there may be a sense that someone has to pay for the massive incompetence that has gotten out of hand.

Perhaps we are about to find out whether mass deception, reckless experimentation with dangerous technologies, and political social engineering have also become akin to aggressive war: whether gross destructive political behavior itself has become a crime against humanity. Although Samuel warned that “we shall be his servants,” the stakes are such that there may be times when the king must go to jail.